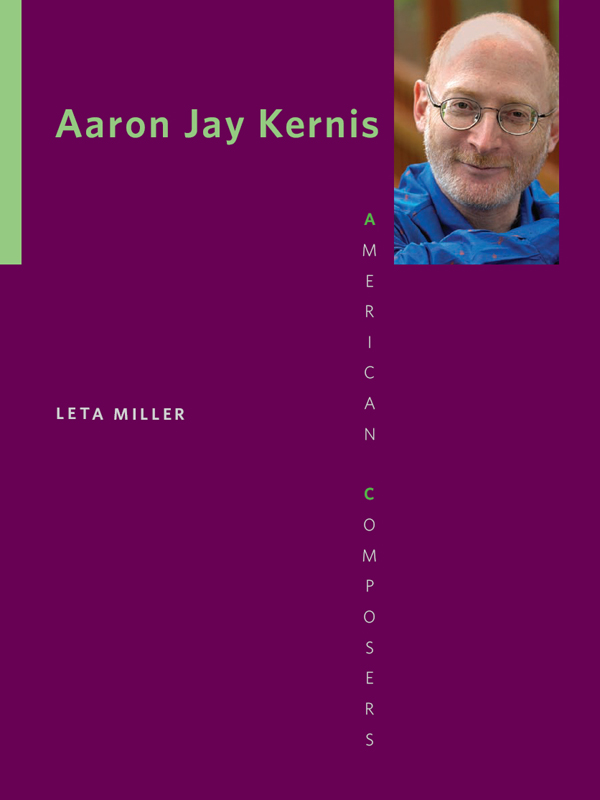

AARON JAY KERNIS

AMERICAN

Composers

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

Aaron Jay Kernis

Leta E. Miller

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS

Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield

Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the Henry and Edna Binkele Classical Music Fund. Supplementary materials, including audio recordings of selected works, can be found on the books Web site: http://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/miller/kernis/.

2014 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miller, Leta E author.

Aaron Jay Kernis / Leta E. Miller.

pages cm. (American composers)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03853-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-08013-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-09644-0 (ebook)

1. Kernis, Aaron Jay. 2. ComposersUnited States Biography.

I. Title.

ML410.K386M55 2914

780.92dc23 [B] 2013050774

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THIS BOOK WOULD NOT HAVE BEEN POSSIBLE without the enthusiastic cooperation of Aaron Jay Kernis, who not only opened his archive of documents to me but also gave unstintingly of his time for interviews and innumerable email messages. He was frank and forthcoming and, although he read every word I wrote (in some cases several times), he allowed me complete independence in interpreting his works and in covering the successes and challenges in his artistic life.

I owe a great debt of gratitude as well to Kerniss wife Evelyne Luest, to his manager Elizabeth Dworkin, and to those who graciously granted me interviews: Marin Alsop, Michael Barone, Jean-Luc Choplin, Andrew Cornall, Eva Gruesser, Linda Hoeschler, Welz Kauffman, Anna Kruger, Rebecca Miller, James Rushton, Marc Satterwhite, Gerard Schwarz, and Hugh Wolff.

The staff at G. Schirmer were extremely helpful, generously providing me with perusal scores without charge and allowing me to search through their large archive of documents. In particular, I thank Katy Tucker and David Flachs. Similarly, staff members at the New York Philharmonic, the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, and the Minnesota Orchestra were very supportive in providing photographs, programs, and other materials needed for my research. Katherine Adamov kindly made available copies of the twenty ISCM films, which are now housed at the library of the University of California, Santa Cruz, in Special Collections.

Others whose generosity aided this project include Laura Kuhn of the John Cage Trust, Vivian Perlis at the Yale Oral History Project, Uziel Adini of Gratz College, and pianist Emanuele Arciuli. Several people agreed to read part or all of the text and offered extremely helpful comments; I thank in particular Peter Cole, Elizabeth Dworkin, and the two anonymous readers engaged by the University of Illinois Press.

I was assisted in this project by grants from the University of California, Santa Cruz, Arts Division and Committee on Research, and by graduate students Giacomo Fiore and Jessica Loranger.

AARON JAY KERNIS

1 Introduction

IM SO PLEASED YOURE WRITING ABOUT ME, said Aaron Jay Kernis when I approached him about this book. My only hesitation is that I feel I should be twenty years older. Indeed, readers may pose the same question: what justifies a book about a composer who is only fifty-four years old?

On the most basic level is Kerniss impressive productivity: the large number of substantial works for forces ranging from solo piano to full orchestra. His current Schirmer catalog lists more than one hundred compositions: a dozen orchestral works (including three large symphonies); another dozen concerti with large orchestra or wind ensemble; a group of works for soloist with chamber orchestra; nearly two dozen compositions for two to six players and the same number of pieces for chorus; fourteen pieces for solo voice accompanied by piano or chamber groups; and a dozen compositions for keyboard. No writing to date has attempted to survey, much less assess, this large body of work. (A catalog of the works discussed in this book appears in the appendix. Selected audio examples, as well as a list of recordings and YouTube excerpts, are included on the books Web site, http://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/miller/kernis/).

Quantity, however, is but one measure of achievement. In Kerniss case, quality has been repeatedly affirmed by a steady stream of awards and commissions, by the enthusiastic reception from renowned performers, and by the strong response Orchestra (Lament and Prayer, 1995), the Seattle Symphony (Symphony of Meditations [Symphony no. 3], 2009), and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra (Symphony in Waves, 1989; Double Concerto, 1996). His works have been played, commissioned, and recorded by esteemed performers such as Pamela Frank, Joshua Bell, James Ehnes, Rene Fleming, Jorja Fleezanis, Truls Mrk, and the Lark Quartet, and they have been programmed by prominent conductors devoted to the music of the United States, including Marin Alsop, Hugh Wolff, and Gerard Schwarz.

Aaron Jay Kernis. (Photo by Richard Bowditch. Used by permission.)

A comprehensive and broadly based examination of the composers stylistic development is thus long overdue. Information about Kerniss music must currently be culled from newspaper and magazine articles, liner notes, and a variety of short interviews, which necessarily address a limited repertoire or time span. In contrast, this book surveys Kerniss work over the course of more than thirty years, detailing both continuities and changes in his musical language. It is based on published documents, personal interviews, and materials in Kerniss extensive collection of programs, reviews, and correspondence. The composer has read the manuscript, clarifying factual details and offering compositional insights but never attempting to censor the contents.

During the period covered in this text, Kerniss compositional path has shown decidedand sometimes quite deliberateturning points. Early works based on strict structural foundations gave way to less rigid conceptual plans, then to an increased focus on classical influences, and finally to his most recent approach, which is highly intuitive. At the same time, his musical development shows distinctive elements of continuitythe markers that define a composers personal voice.

The turning points serve to delineate creative periods. Compositions from Kerniss pre-college and college years (through 1983) tend to be process-oriented; he imposed on himself severe rhythmic or melodic constraints sometimes akin to minimalist aesthetics. From 1984 through the beginning of the 1990s, he began to free himself from such restrictions. Developing greater confidence in his intuition, he allowed broader conceptual stimuli to guide his creative process, thereby discovering a more personal means of expression. This transformation led him unexpectedly toward Classical forms such as the symphony and string quartetgenres steeped in historical tradition. His Symphony in Waves (1989) arose from this new embrace of tradition, as did his first string quartet (1990), in which Kernis integrated his increasingly individualistic voice with forms solidified in the late eighteenth century: sonata-allegro, theme and variations, scherzo, and rondo.

Next page

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.