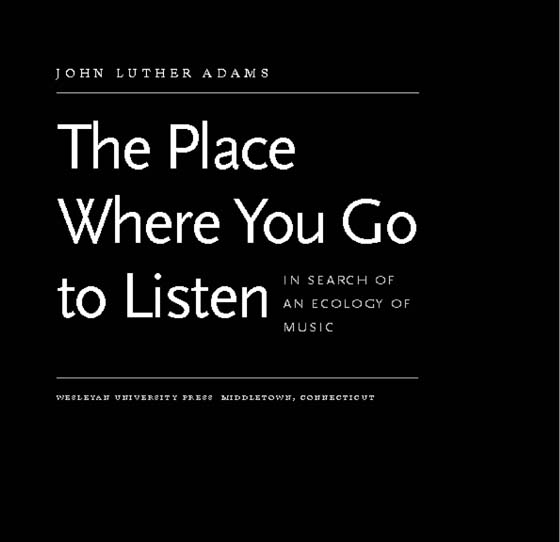

The Place Where You Go to Listen

Published by Wesleyan University Press,

Middletown, CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2009 by John Luther Adams

Foreword by Alex Ross excerpted from

Song of the Earth, The New Yorker, May 12, 2008.

Used by permission.

All rights reserved

Printed in U.S.

5 4 3 2 1

Wesleyan University Press is a member of the GreenPress Initiative. The paper used in this book meets their minimum requirement for recycled paper.

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Adams, John Luther, 1953

The place where you go to listen : in search of an ecology of music / John Luther Adams ; foreword by Alex Ross.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8195-6903-5 (pbk.)

1. Adams, John Luther, 1953- 2. ComposersAlaskaBiography. 3. Adams, John Luther, 1953Place where you go to listen. I. Title. ML410.A2333A3 2009

780.92dc22

[B] 2008054108

Contents

Illustrations

FIGURES

PLATES (following )

Foreword ALEX ROSS

On a recent trip to the Alaskan interior, I didnt get to see the aurora borealis, but I did, in a way, hear it. At the Museum of the North, on the grounds of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, the composer John Luther Adams has created a sound-and-light installation called The Place Where You Go to Listena kind of infinite musical work that is controlled by natural events occurring in real time. The title refers to Naalagiagvik, a place on the coast of the Arctic Ocean where, according to legend, a spiritually attuned Iupiaq woman went to hear the voices of birds, whales and unseen things around her. In keeping with that magical idea, the mechanism of The Place translates raw data into music: information from seismological, meteorological and geomagnetic stations in various parts of Alaska is fed into a computer and transformed into an intricate, vibrantly colored field of electronic sound.

The Place occupies a small white-walled room on the museums second floor. You sit on a bench before five glass panels, which change color according to the time of day and the season. What you notice first is a dense, organlike sonority, which Adams has named the Day Choir. Its notes follow the contour of the natural harmonic seriesthe rainbow of overtones that emanate from a vibrating stringand have the brightness of music in a major key. In overcast weather, the harmonies are relatively narrow in range; when the sun comes out, they stretch across four octaves. After the sun goes down, a darker, moodier set of chords, the Night Choir, moves to the forefront. The moon is audible as a narrow sliver of noise. Pulsating patterns in the bass, which Adams calls Earth Drums, are activated by small earthquakes and other seismic events around Alaska. And shimmering sounds in the extreme registersthe Aurora Bellsare tied to the fluctuations in the magnetic field that cause the northern lights.

The first day I was there, The Place was subdued, though it cast a hypnotic spell. Checking the Alaskan data stations on my laptop, I saw that geomagnetic activity was negligible. Some minor seismic activity in the region had set off the bass frequencies, but it was a rather opaque ripple of beats, suggestive of a dance party in an underground crypt. Clouds covered the sky, so the Day Choir was muted. After a few minutes, there was a noticeable change: the solar harmonies acquired extra radiance, with upper intervals oscillating in an almost melodic fashion. Certain that the sun had come out, I left The Place and looked out the windows of the lobby. The Alaska Range was glistening on the far side of the Tanana Valley.

When I arrived the next day, just before noon, The Place was jumping. A mild earthquake in the Alaska Range, measuring 2.99 on the Richter scale, was causing the Earth Drums to pound more loudly and go deeper in register. (If a major earthquake were to hit Fairbanks, The Place, if it survived, would throb to the frequency 24.27 Hz, an abyssal tone that Adams associates with the rotation of the earth.) Even more spectacular were the high sounds showering down from speakers on the ceiling. On the Web site of the University of Alaskas Geophysical Institute, aurora activity was rated 5 on a scale from 0 to 9, or active. This was sufficient to make the Aurora Bells come alive. The Day and Night Choirs follow the equal-tempered tuning used by most Western instruments, but the Bells are filtered through a different harmonic prism, one determined by various series of prime numbers. I had the impression of a carillon ringing miles above the earth.

On the two days I visited The Place, various tourists came and went. Some, armed with cameras and guidebooks, stood against the back wall, looking alarmed, and left quickly. Others were entranced. One young woman assumed a yoga position and meditated; she took The Place to be a specimen of ambient music, the kind of thing you can bliss out to, and she wasnt entirely mistaken. At the same time, it is a forbiddingly complex creation that contains a probably irresolvable philosophical contradiction. On the one hand, it lacks a will of its own; it is at the mercy of its data streams, the humors of the earth. On the other hand, it is a deeply personal work, whose material reflects Adamss long-standing preoccupation with multiple systems of tuning, his fascination with slow-motion formal processes, his love of foggy masses of sound in which many events unfold at independent tempos.

The Place, which opened on the spring equinox in 2006, confirms Adamss status as one of the most original musical thinkers of the new century. At the age of fifty-five, he is perhaps the chief standard-bearer of American experimental music, of the tradition of solitary sonic tinkering that began on the West Coast almost a century ago and gained new strength after the Second World War, when John Cage and Morton Feldman created supreme abstractions in musical form. Talking about his work, Adams admits that it can sound strange, that it lacks familiar reference points, that its not exactly popularby a twist of fate, he is sometimes confused with John Coolidge Adams, the creator of the opera Nixon in China and the most widely performed of living American composersand yet hell also say that its got something or, at least, Its not nothing.

Above all, Adams strives to create musical counterparts to the geography, ecology and native culture of his home state, where he has lived since 1978. He does this not merely by giving his compositions evocative titleshis catalog includes Earth and the Great Weather, In the White Silence, Strange and Sacred Noise, Dark Waves but by literally anchoring the work in the landscapes that have inspired it.

My music is going inexorably from being about place to becoming place, Adams said of his installation.

I have a vivid memory of flying out of Alaska early one morning on my way to Oberlin, where I taught for a couple of fall semesters. It was a glorious early-fall day. Winter was coming in. I love winter, and I didnt want to go. As we crested the central peaks of the Alaska Range, I looked down at Mt. Hayes, and all at once I was overcome by the intense love that I have for this placean almost erotic feeling about those mountains. Over the next fifteen minutes, I found myself furiously sketching, and when I came up for air I realized, There it is. I knew that I wanted to hear the unheard, that I wanted to somehow transpose the music that is just beyond the reach of our ears into audible vibrations. I knew that it had to be its own space. And I knew that it had to be realthat I couldnt fake this, that nothing could be recorded. It had to have the ring of truth.

Next page