First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2013

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-015-5 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-009-5 in EPub format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-100-8 in Mobipocket format

Cover design by Ana Bjezancevic

Designed and typeset by Envy Design Ltd

Picture research by Judith Palmer

www.mombooks.com

For Rhona, my own personal gift from

the Princes of Serendip

Introduction

A CKNOWLEDGED AS ONE of the most difficult words to translate into any other language, serendipity as a word and a concept was invented by Horace Walpole, son of Robert Walpole (who is broadly recognized as Britains first Prime Minister, despite that office not existing until 1937 all previous incumbents being formally titled First Lord of the Treasury; but we digress). Horace was inspired by the ancient tale of The Three Princes of Serendip the old name of Sri Lanka which tells of many discoveries and situations successfully resolved by chance or blunder, as indeed has been the case throughout the history of science and medicine.

Take, for example, the discovery of PTFE, better known today as Teflon. Although non-stick pans are cynically and wrongly said to be the only benefit accorded the general population by the space programme, the substance was in fact discovered by chance in 1938 by Du Ponts Roy Plunkett while he was working on refrigerants. A cylinder of tetrafluoroethylene gas failed to discharge, despite the fact that its weight indicated that it was full. At this point most would have simply grabbed another cylinder, but not Plunkett, who cut the cylinder in half to see what was going on. The inside was coated with a white deposit indicating the gas to have polymerized. This white deposit has meant omelettes have been easier to cook ever since.

Sticking with the American space programme, serendipity can also work in reverse, chronologically speaking. In 1962, NASA was struggling to design the spacesuits that, in 1969, would be worn by the first men on the moon. In a chance conversation, one of the team was correcting a colleague who had trotted out the old myth about armour being so heavy that knights had to be hoisted onto horses by small cranes. While lecturing his teammates on the lightness and flexibility of such suits that in fact rarely weighed more than 50lb, it dawned on all present that the answer to their problem might lie in the past. The team flew hot-foot to the UK to visit the armouries at the Tower of London and subsequently modelled their famous moon attire on a suit of armour made for Henry VIII to fight on foot in knightly contests. The secret lay in the articulation of all the joints, which allowed for full radial movement. Today, visitors to the Tower can still see the moonsuit sent from America in gratitude, standing aside its historical inspiration.

There are, of course, many more examples of serendipitous discovery than those included in the following pages even the recreation drug ecstasy evolved from a 1953 search for a truth-drug conducted by the US Army but everyone involved in the project hopes you enjoy the stories laid out in The Accidental Scientist and will perhaps be encouraged to seek out more examples. (Actually, I wanted to call it Serendipity-Do-Dah but they put the block on that pretty smartish.)

Botox

T OXINS CAN BE FUNNY THINGS ; some, like snake venom, which is little more than a modified enzyme that pre-digests the snakes prey, are lethal if administered intravenously yet can be ingested without harm. Others, like botulism, can be lethal if ingested yet benign or even beneficial if injected under the right conditions.

Usually associated in the general mind with contaminated meat, Clostridium botulinum is also pandemic in the soil and finds low-acid vegetables, such as asparagus, an ideal host; most dangerous of all is the humble baked potato if wrapped in baking foil after cooking and then left at ambient temperature. The first to suspect the existence of this toxin was the German poet/physician Justinus Kerner (17861862) who, in his home town of Wrttemberg in 1817, traced an outbreak of such food poisoning to a batch of boiled sausage and so named the culprit from the Latin botulus, a sausage. Such outbreaks were far more common in Wrttemberg than in other towns and cities, an anomaly Kerner speculated might be due to the local habit of slow and low temperature boiling to reduce the likelihood of the sausage bursting; furthermore, although he had no idea as to the nature of the agent, he was the first to speculate on possible medical uses. But it would be a chance invitation to, of all things, a funeral, seventy-eight years later, that cracked the matter.

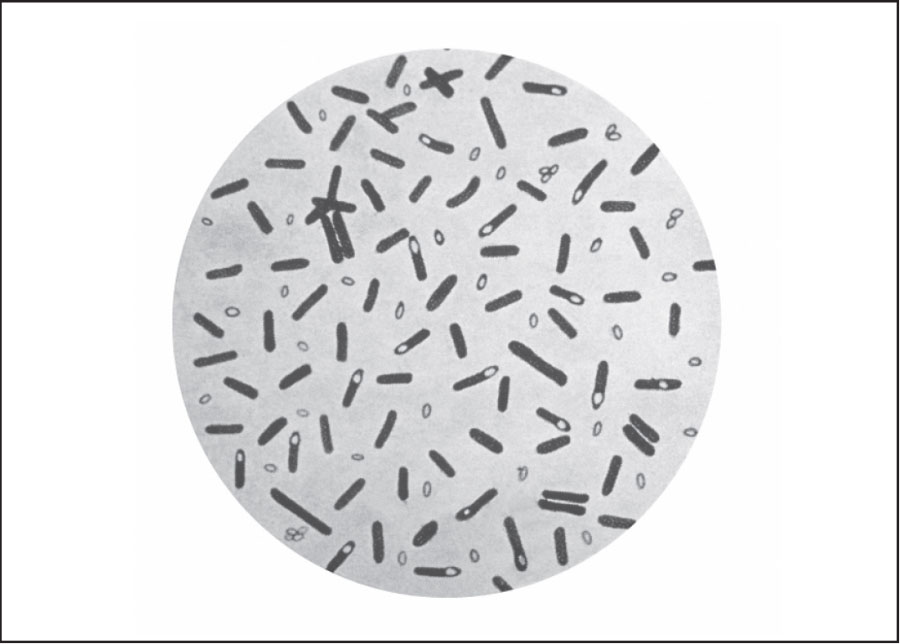

Clostridium botulinum

OOMPAH

On 14 December 1895, the Belgian microbiologist Emile van Ermengem (18511932) was attending the funeral of one Antoine Creteur, in the farming community of Ellezelles where he was living at the time. Present at the post-interment shindig was the Fanfare Les Amis Reunis, a still-extant brass band famed throughout modern Belgium. After their efforts, the band members took themselves off to Le Rustic tavern for beer and a snack of the locally produced air-dried and smoked ham; a speciality not unlike Parma ham. Soon, most of the thirty-four band members started presenting symptoms of blurred vision, flaccid muscles and slurred speech, a not uncommon experience after a long session in a pub, but then they started dying. Three of the youngest musicians were the first to succumb: Jules Hautru and Angel Deltenre, both nineteen-year-old farm labourers, and a twenty-two-year-old saddler Firmin Cretuer, a relative of the recently interred.

The crucial factor, of course, was that the handful of musicians who had shunned the ham in favour of other foods remained fit and well, this giving Ermengem a God-given opportunity to immediately identify the source and set to work.

He returned to his laboratory in the University of Ghent with samples of the ham, which was liquidized and injected, fed to or implanted under the skin of assorted rabbits, dogs and monkeys, all of which took rapid onset of identical symptoms and died. Within a matter of weeks he had isolated and identified the bacterium responsible and published papers on its nature and, more importantly, how to eliminate its growth in the air-dried ham process.