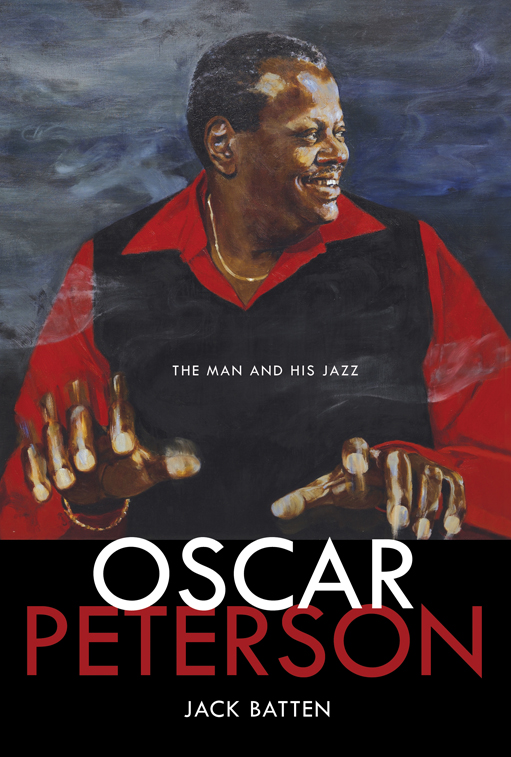

Copyright 2012 by Jack Batten

Published in Canada by Tundra Books,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited,

One Toronto Street, Suite 300, Toronto, Ontario M5C 2V6

Published in the United States by Tundra Books of Northern New York, P.O. Box 1030, Plattsburgh, New York 12901

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011940582

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Batten, Jack, 1932

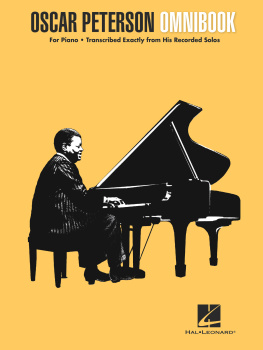

Oscar Peterson : the man and his jazz / by Jack Batten.

eISBN: 978-1-77049-362-9

1. Peterson, Oscar, 1925-2007 Juvenile literature. 2. Pianists Canada Biography

Juvenile literature. 3. Jazz musicians Canada Biography Juvenile literature.

I. Title.

ML3930.P463B33 2012 J786.2165092 C2011-907065-0

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and that of the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Media Development Corporations Ontario Book Initiative. We further acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program.

v3.1

For Ken

In researching and writing this book, I benefitted enormously from conversations over many years with the jazz pianists Don Thompson and Gene DiNovi, the jazz archivist Ken Crooke, the late jazz journalist Gene Lees, and the all-round cultural journalist Robert Fulford. I also owe much to many biographies of jazz musicians, most notably Peter Pettingers Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings and Mark Millers many books. I owe much to the Toronto Reference Library and the City of Toronto Archives, and even more to the all-round editorial talents of Sue Tate.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

OSCARS

EXCELLENT

DEBUT

O n the night of Sunday, September 18, 1949, the temperature climbed to a sweltering eighty degrees Fahrenheit inside New York Citys historic Carnegie Hall. All summer, intense heat had covered the city like a smothering blanket. But the oppressive atmosphere on this September night didnt bother Carnegie Halls packed rows of excited jazz fans. They raised the halls temperature even higher, cheering and hollering for the musicians onstage.

The players performed under the title Jazz at the Philharmonic. JATP, as it was popularly known, had been organized six years earlier by an aggressive music promoter from California named Norman Granz. Under Granzs guidance, the troupe made an annual three-month North American tour, selling out every concert hall Granz booked.

JATPs personnel of a dozen to fifteen musicians underwent changes from season to season, but it always included a core of Granzs favorites. Among those in the lineup on this night at Carnegie Hall were the sizzling trumpet player Dizzy Gillespie; the dynamic drummer Buddy Rich; and the agile and swinging singer Ella Fitzgerald.

All the JATP players were superb musicians, capable of projecting a wide range of moods. And each night, they offered a handful of gently explored ballads. But Granz insisted that his people emphasize their extroverted side. He liked battles between two drummers alone onstage, dueling against one another. And he loved tenor saxophone wars, one tenor challenging another in solos that climaxed in startling runs to the top of the instruments range.

The musicians went along with Granzs preferences because it was clear to them that his strategy worked. Big crowds turned out for the competitive concerts; the musicians earned far more money than they were accustomed to; and Granz had made himself the most powerful man in jazz.

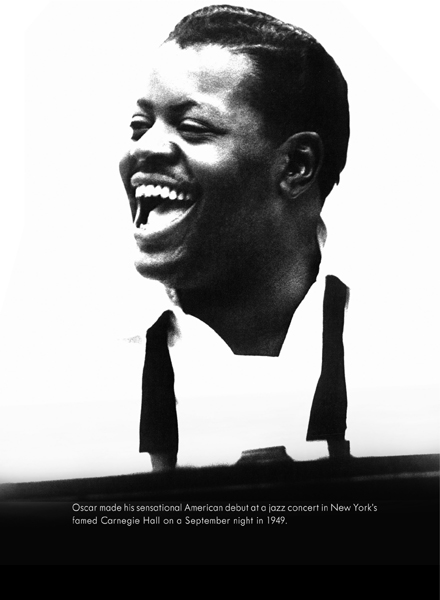

Oscar Peterson, sitting in the front row through the first half of the September 18 concert, wiped his forehead with a massive white handkerchief. Oscar was feeling the heat. Just turned twenty-four, he stood six-foot-two and weighed 250 pounds. Oscars size made him one of natures perspirers. But the sweat also reflected mild anxiety.

In the second half of the concert, Granz was going to introduce Oscar as a surprise JATP guest artist. From Montreal, Quebec, the Canadian pianist would make his American debut in the countrys most illustrious concert hall.

Only a few American jazz fans, in or out of the hall, were aware of Oscar and his music. Granz was one of the rare exceptions, having heard Oscar play in a Montreal club a few weeks earlier. He found Oscars jazz vigorous and thrilling. Not a man to pass up a golden opportunity, Granz proposed on the spot that Oscar perform at the September JATP concert in New York.

Oscar could think of several reasons why this was a terrible idea. He didnt have a visa allowing him to work in the United States or a musicians union card that was recognized in New York City. Granz brushed off the objections. He told Oscar that his appearance at Carnegie Hall would be as guest artist. Guests didnt need visas or union cards. But Oscar insisted he wasnt yet good enough to face a demanding New York audience. Baloney, Granz said, Oscar was as ready as any musician hed ever met.

As Oscar raised his doubts, he eventually reacted the way everybody did when Granz had made up his mind about something: He gave in.

When Oscar headed backstage during the September 18 intermission, he knew he would be playing with the JATP bassist Ray Brown. Oscar was a big fan of Browns work. Oscar had even chatted with him two or three times, when Brown was passing through Montreal and stopped for a drink at the club where Oscar was appearing.

Now, backstage, Oscar and Ray talked about tunes they might play. As Oscar expected, the two were on the same musical wavelength. Oscars nervous tingles slipped away. He was ready to play.

At the opening of the concerts second half, Granz, who acted as master of ceremonies at all JATP concerts, announced to the audience that he had a special treat for them a new pianist from Canada. He gestured for Oscar and Ray Brown to come forward from the wings.

So it was that Oscar Peterson walked to center stage at Carnegie Hall for the performance that would change his life forever.

Oscar and Ray Brown played three tunes. One was a familiar Broadway show tune titled Fine and Dandy. The second was an equally popular movie song, I Only Have Eyes for You. And the third was a simple blues tune, which Oscar and Brown made up then and there and named Carnegie Blues.

Virtually from the first note of the first song, Oscar had the listeners in the palm of his hand. They were enthralled, all of them taken by the sensational and fresh-sounding musician suddenly in their midst.

The audience of reasonably sophisticated jazz fans recognized that Oscar was different from other pianists of his generation. Among Oscars contemporaries, the accepted style was to emphasize the right hand; with the left, these pianists played one or two chords in each bar while the right hand ran all over the upper half of the keyboard, throwing off single-note improvisations.

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)