Copyright 2008 Bobcat Books

This edition 2010 Bobcat Books

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London W1T 3LJ)

ISBN: 978-0-85712-370-1

The Author hereby asserts his / her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Visit Omnibus Press on the web: www.omnibuspress.com

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

For

Ruth, who gave me her books

Bill, who gave me rhythm

Jon and Carrie, who taught me love

Brendan, for constant inspiration and

Judy

without whom Id never get anything done.

Acknowledgements

My sincerest of thanks are given to the following people and organisations who have given me so much help and time in making this book possible.

Ace Records, Charles Alexander (Jazzwise), Elizabeth Anionwu, Archives de lAssistance Publique et Hpitaux de Paris, Martin Allerton (Mole Jazz), Peter Anick (Fiddler magazine), Anthony Barnett, Alan Bates, Eileen Baxter, Don and Pauline Bishop for the Alcantara information, Robert Bridson for his album designs, British Newspaper Library, Christine Caine for apple pie and faith, Benny Carter for being patient, Ted Cherrett for The Genius That Was Django, Penny Chilton, Arantes Coelho Neto, Shalom Cohen for valour, Eileen Cohen, Concord Records, Conservatories de la Ville de Paris, Conservatoire National Superieur, Iain Cruickshank for Djangos Gypsies and The A-Z Of Django, DA Music, Irving David, Jim Davis for inspiration, Jim Di Giovanni, John Duarte for services to music and good humour, EMI Classics, Roland H Flyge II, Pete Frame, Fremeaux & Associates, Matt Glasser, Ted Gottsegen, Chris Gower (Kingsland Colour Studio), Stephen Graham (Jazzwise), David Grisman, Clifford Hocking, Imperial War Museum, Ivor Mairants, Christine Jacquemart for opening doors, Lisa Jenkinson (BBC Desert Island Discs), John Jeremy for passing the baton (I will try to run true and straight!), Pete Johnson, Lesley Kelsall, Graham Langley (British Institute of Jazz Studies), Georg Lankester (Hot Club de France), Holland Foundation for many tapes and photos, Brendan McCormack (Mind Scaffolding Inc), Andy McKenzie, Mactwo, Marc Masselin, Carl B Margereson (Senior Lecturer in Adult Nursing, Thames Valley University), Melody Maker (IPC Media), Muse de Montmartre, Muse de Musique, Daniel Nevers for brilliant transcriptions and detective work, Mark Blair-Flyge Ostrian, Patrice Panassi, Pat Philips, Mike Piggott, RCA Victor, Babik Reinhardt for agreeing to talk, Malcolm Rowland for services to the Home Guard and of the precious discs, Steve Royall, Alyn Shipton, Andrew Simmons (National Sound Archive), my sisters Jean and Ruth for their love and putting up with the noise, Geoffrey Smith for his excellent book on Grappelli and his personal encouragment, Flix W Sportis, Yves Sportis (Jazz Hot) for so much personal help and also access to all the pre-war Jazz Hot archive, John Steadman (JSP Records), Marcel and Jean Stellman, George Shearing for that fantastic Shearing sound, Jon-Luc Ponty, Ettore Stratta, Maurice Summerfield for his excellent version of the Delaunay book Django Reinhardt, Tony Swain for editing and faith, James Taylor, Time Warner Books, Alan and Beryl Williams for believing, Bee and Walter Wyeth for book research, Sarah Young. A special thank you to David Greenaway and Dyanna Swindlehurst for so much encouragement and belief.

Authors Note

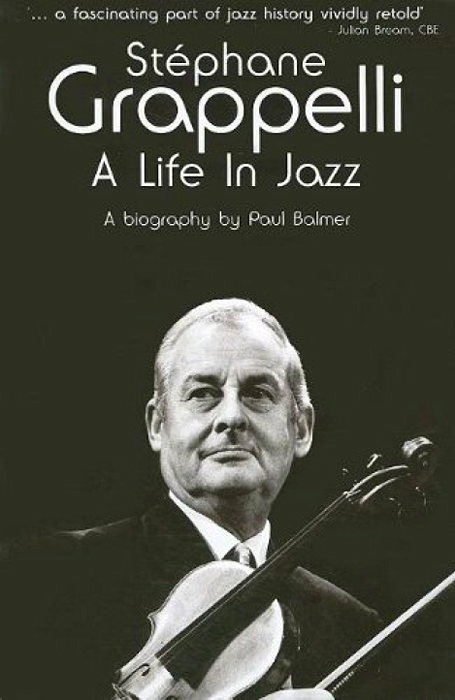

In his Paris home and the infamous cabaret Le Lapin Agile, Stphane Grappelli told me his astonishing story. I discovered that, like so many of us, he was always in search of himself. To this end, he collected scraps of evidence. Clues.

In a dresser in his music room, he kept an oil painting and a lock of a lovers hair. These were all that remained of Gwendoline Turner, the woman he tragically lost in the London Blitz of 1940. He also kept a lock of his Italian fathers hair and a letter from the gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt.

There was a cartoon of Montmartre street urchins by Poulbot. A little book on the Paris district of Rochechouart. These areas he described as my Quartier.

In his cellar at home he kept a set of cardboard shoeboxes full of hundreds of photographs snaps and publicity stills. There was a portrait of Frank Sinatra signed, To Stphane Grappelli, a great artist. There were theatre hoardings, including music-hall posters and photographic exteriors Carnegie Hall Sold Out, picturing some of his friends waving to the camera. There were also many rare photographs of the musical life of the 20s and 30s.

Stphane kept a bank account, opened to help his father, but was saddened to find, after his death, that his father had left it uncashed.

There were other clues in the Rue Dunkerque flat: the portrait of Art Tatum over his piano; the Grappelli driving licence from 1953 the year that Django Reinhardt died and when Grappelly again became Grappelli.

From 1953, the mythology of Django haunted Stphane and his music-making. When I first met Stphane in 1978, like so many others I made the error of mentioning Django his eyes instantly went up to heaven (but only metaphorically; he was too polite to be rude). Legend is a difficult cross to bear. The Django myth is self-perpetuating even for people incapable of understanding Reinhardts enigmatic music. So Stphane would be quizzed frequently about Django, often by people who had never heard of Duke Ellington. He sent them away, telling them to come back when they knew the questions.

Unfortunately, the Django mythology clouded many peoples understanding of Grappellis genius. Stphane knew this but was too pragmatic a man ever to complain. If people saw him in Djangos reflectionwell, at least they saw him; many of his musical friends had been completely ignored. Outside the closed jazz fraternity, few bothered to understand Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster or Art Tatum. This is Stphanes life, with and without Django.

Stphane was a very private man, but here Ive included the impressions of others to illustrate the character of the man. John Etheridge, who toured the world with him for five years, observed, He never got that close to any of us. But John is a perceptive man and a powerful musician, his own man with his own music.

Martin Taylor expresses himself best through music hes surely one of the worlds greatest jazz guitarists. When he spoke of Stphane, he eventually gave up on words and played Manoir de mes Rves try to hear it if you can; its an eloquent tribute. Above all, enjoy his musicianship; he and John Etheridge carry the lions share of the Grappelli legacy.

Edward Baxter, Stphanes UK agent, made my interviews with Stphane happen, despite the lack of funding. He had vision.