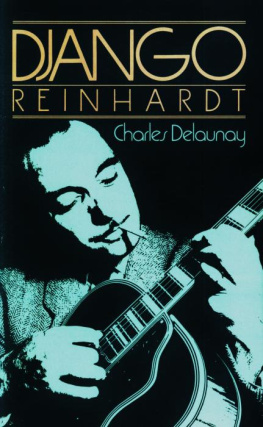

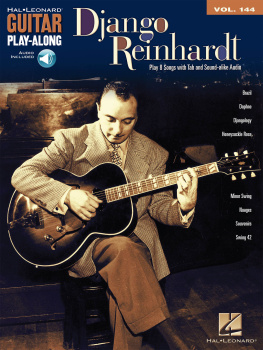

Charles Delaunay

France

Django Reinhardt

1961, EN, 57757 words

No European jazz musician has so enchanted the word as Django Reinhardt, the gypsy guitarist whose recording with Stephane Grappelly and the Hot Club of France have meant The Thirties to several generations of listeners, influencing musicians as far afield as Larry Coryell, Leon Redbone, Eddy Lang, and Charlie Christian. This is the only full-length study of Django ever published in English, an unforgettable portrait of a wild and independent figure who never learned to read or write (friends forged his autographs), exasperated those people who lived by schedules, gambled away a weeks salary in a night, but who played the guitar like no one before or since. The distinguished French critic Charles Delaunay, who knows more about Django than anyone alive, here provides not only the familiar outline of a life the childhood travels in gypsy caravans, the fire that left Django with a crippled hand, the legendary temper and generosity but he also collected scores of anecdotes about the sensitivity and musical gifts that were the basis for Djangos appearance as a character in Jean Cocteaus Les Enfants Terribles. Who else but Django could charm his way out of a jail sentence by serenading the police officer with his guitar? The comprehensive discography at the back of the book completes Delaunays picture of this misrepresented and fantastic creature, at once so captivating and so divorced from the contentions of his age.

Foreword

S hortly after Django Reinhardts death I published a small collection of personal memories and anecdotes I had made a mental note of during the many years I knew this remarkable performer. The booklet was very soon out of print; instead of being forgotten, the name of Django Reinhardt continued from that day onwards to become better known. During his lifetime he was regarded as an exceptional figure, and the imagination of certain unscrupulous journalists (most of whom had never known him) led them to substitute a spurious legend for the real one, far more extraordinary in its way, which was none other than the everyday life of the artist.

The aim of this book, therefore, is faithfully to reconstruct the career of the famous wandering guitarist, by means of the very persons who lived and worked with him: his relatives and the musicians who knew him best. During the many months I devoted to my researches I felt it incumbent upon me to appeal to everyones memory, comparing and checking the various accounts and even visiting libraries to consult the magazines and newspapers of the period in order to verify events that people could not always remember with certainty. If the task was considerable, and in more ways than one recalled the time-honoured methods of criminal investigation, it was made absorbing by the interest the subject held for me and the goodwill I met at everybodys hands.

This book, then, is not the fanciful tale which would have tempted any writer, but the unvarnished account, straight from the mouths of the artists acquaintances. These people, I feel, will reveal the man in his truest, most human and most poetic light, too, and will allow the reader to form his own idea of this misrepresented and fantastic character, at once so captivating and so divorced from the conventions of his age.

Charles Delaunay

1

The Man

D jango was an exceptional person. From his earliest youth he stood out from his fellows by virtue of a natural beauty and nobility which won him the respect and veneration that are the birthright of chiefs. Taller than most French-speaking gipsies, with wide shoulders only with the passage of years did his back become bent his whole figure gave the impression of contained power.

Manouches in the text (translator). The French language distinguishes between Manouches, French-speaking gipsies; Romanis, who speak Italian; Gitans, who speak Spanish; and the Central European Bohemian, who generally speak a sort of German dialect.

He enjoyed no mean physical strength, a natural strength which he owed to the active outdoor existence of his youth, when his caravan was always on the move.

He had a liking for broad-brimmed hats, generally light in colour, which threw his swarthy complexion into relief and drew attention to his almond-shaped eyes, with their pupils that glowed fiercely like embers in the night. A narrow moustache by now legendary put the finishing touch to his well-formed countenance.

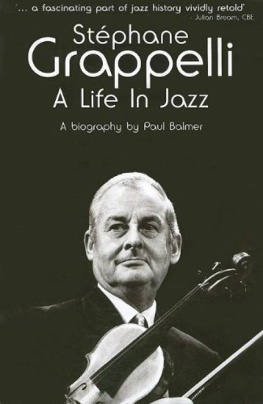

Although he was born in poverty, Django had the soul of a nobleman. He felt an instinctive affection for elegance. Whilst this, I suppose, was a basic trait in his character it asserted itself only by degrees, for gipsy life offers little scope to such a taste. I shall never forget, Stphane Grappelly reminds us, the first day Django put on evening dress with bright red socks. It took some time to explain, without injuring his feelings, that red socks were not the right thing. Django insisted that he liked it that way, because red looked so well with black.

Stphane Grappelty, the Melody Maker, March 6, 1954.

Sometimes he would appear dressed with great care, in a suit from the best tailor, a silk shirt and a silk tie, the image of some West End dandy. The afternoon, however, would find him sporting a pullover and baggy corduroy trousers, top-boots and round his neck a many-hued scarf which spoke all too eloquently of the enthusiasm the gipsies feel for brightly coloured silks. He would lounge about the streets of Montmartre, pausing to chat on the caf forecourts, ever on the lookout for a game of billiards or poker with the layabouts of the neighbourhood.

Despite the grave shortcomings of his education he never really learnt how to write his natural ease of manner and aristocratic bearing meant that he was never out of place in polite society, where he knew how to be sophisticated, sometimes gallant and often witty. It is in this lack of education and, above all, of culture, that we must look for the explanation of a life which hinges upon legend, one whose events seem hopelessly incoherent. Until he was twenty, Django had never worn a proper suit; he had never lived in a house; he had stayed a typically primitive, medieval gipsy, whose archaic beliefs, superstitions and mistrust of the benefits of science are reminiscent of the mentality of the peasants who fled in terror at the approach of the first railway trains. Brought up as he was in his caravan, on the fringe of modern life, at the very gates of a big city, who can imagine what it meant for him and his family to leave their clan and settle in a house? M. Savitry, who was responsible for this event, tells how, in the space of a few weeks, the whole gipsy tribe of the outer Paris suburbs was roaming round his new dwelling, intent on assuring themselves with their own eyes that their brother had not been kidnapped or otherwise mistreated, that he really was not locked up. Skirting the walls, like conspirators they cast terrified glances about them, and curiosity alone gave them the courage to face so great a trial. For it is not so long ago that gipsies used to carry off little children; and if townsfolk have forgotten this, the story is still repeated to terrorize naughty toddlers wherever their caravans are to be found.

This anecdote shows better than any description just how undeveloped these people have remained; living on the outskirts of our large modern cities, they have nonetheless jealously preserved their way of life and their beliefs. It also makes it easier to understand what kind of a man was Django Reinhardt in 1953 when, all of a sudden, success was to transplant him into a world so different from the one into which he had been born. This change of fortune also meant that Django broke away from the Oriental traditions which prescribe that man should never work, and, far from having to earn money, should take care only to spend it; and which decree that woman instead should toil, priding herself only on possessing a man who is well-dressed, leisured and the cynosure of every eye.

Next page