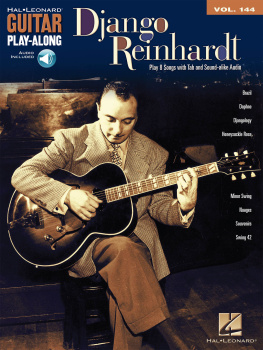

Django: The Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend

Michael Dregni

Contents

Django

Like us

you have no king

no set of rules

but you have a mistress:

Music

Manouche poet Sandra Jayat, Django, 1961

Django, il tait la musique fait lhomme.

Emmanuel Soudieux

Awakening 1910 19 2 2

He was known as Django, a Gypsy name meaning I awake. His legal namethe name the gendarmes and border officials entered into their journals as his family crisscrossed Europe in their horsedrawn caravanwas Jean Reinhardt. But when the family brought their travels to a halt alongside a hidden stream or within a safe wood to light their cookfire, they called him only by his Romany name. Even among his fellow Gypsies, Django was a strange name, a strong, telegraphic sentence due to its first-person verb construction. It was a name of which Django was exceedingly proud. It bore an immediacy, a sense of life, and a vision of destiny.

He was born in a caravan at a crossroads in the dead of winter. Following the dirt paths and cobblestone roads north from the Midi of France in the fall of 1909, his father, Jean-Eugne Weiss, steered the familys single horse to pull their caravan creaking and swaying onto the wide open plains of Belgium. Here, the land was so flat it gave the impression one could see to the ends of the earth. The wet wind whipped down from the Atlantic unimpeded in its cold fury. Riding on the wind came dark rains that seemed never-ending, turning day into night for months on end until one prayed for even the weakest rays of sun. Reining in his horse, Jean-Eugne brought the familys perennial travels to a halt at the crossroads of Les Quatre Bras. As they had done for countless years past, the family would weather the winter in a rendezvous outside the Belgian village of Liberchies in the southwestern Hainaut region. They camped amid a small troupe of fellow Romanies to huddle through the coldest months alongside the Flache s Corbsthe Pond of the Ravens named for a coven of the black birds that haunted the surrounding trees. With fresh water from a stream and fodder for their horse from the fallow fields, the family settled in as much as they ever settled anywhere.

Jean-Eugnes caravancalled a vurdon in Romany and roulotte in French was a typical Gypsy home of the era. The family lived in a wooden box measuring roughly seven feet wide by fourteen feet long and six feet high. This box was mounted atop two axles bearing wooden-spoked wheels. Traces and tack held their single horse while a simple bench supported the driver. At the rear, steps led to the entry door. The typical Romany caravan of the time had small windows on either side letting in daylight; these windows were covered by handcrafted lace curtainsthe kind of domestic touch that made a caravan a home. Inside, a cast-iron stove was bolted to the floor; fed on wood and coal, it glowed transparent red in the winter and warmed the whole of the caravan. Across the front end, a bedchamber dominated, surmounting chests of drawers storing belongings, quilts, and blankets. A corner of the caravan was set aside as a shrine with a framed lithograph turned into an object of worship. The image depicting the French Gypsies patron saint, Sara-la-Kli, was draped with strands of vari-colored beads and lit by votive candles. Underneath the caravan hung wooden crates containing tarps, tools, water buckets, feed for the horse, and cages for ducks and chickens that might be spirited away from farmsteads along the road. Running the roofline and around the doorway was carved scrollwork painted in the most brilliant golds, scarlets, and indigos possible and shining like a gilt crown on a religious effigy. Within this small home-on-wheels lived the family: Jean-Eugne, his wife Laurence Reinhardt, Jean-Eugnes ten-year-old daughter, and another, younger son, both of whose names have been lost.

Beyond the half-moon rooftop and spindly stovepipe of the familys caravan, the staunch red-brick houses of Liberchies led up to the grand gothic church of Saint-Pierre-de-Liberchies, its heavenward spire towering high over the level countryside. The Belgians said of themselves that they were born with a rock in their stomach to start building their houses, so infatuated were they with their homes and the security of a firm foundation. Now, in wintertime, the solid houses of the 700 inhabitants of Liberchies were warmed by charcoal braziers. Electric radios bringing news of the world and diversion in the dark evenings were winning pride of place on mantels. And around town, the automobile was coming to rule the roads, terrifying Romany horses as the horseless carriages rattled by. The modern world of 1909 had left the Gypsies in its dust.

Still, the arrival of Jean-Eugnes family and their kumpania, or traveling clan, of Gypsies was celebrated each autumn by the people of Liberchies with a bazaar organized in their honor, the Kermesse du Fichaux. Swirling with color into the gray of a Belgian fall, the Gypsies sold the jewelry, baskets, and lacework they fashioned as well as wares from their far travels. They told fortunes, unwinding the paths of a life from the tangle of lines on a palm, auguring greatness and love, selling charms to ward off evil. Some specialized in mending wicker chair seats. Others patched copper cooking pots the Belgian village women brought; with a concerto of pounding, a pot could be

made as good as new with metalwork changed little since the armoring of knights. Still other Gypsies traded horses with the farmers, wheeling and dealing, examining teeth for age and hooves for lameness. The Gypsies were known as maquignonsliterally, horse fakerswho magically dressed up horses for sale, and the farmers looked for their timeless trademark tricksshoe polish hiding grizzled hair, a diet of water to fill out ribcage staves, a spike of ginger in the anus for spirit. It was all an ages-old exchange between the Gypsies and townspeople of Europe.

Jean-Eugne was un vanniera basketmaker. Yet he also wore other hats, a necessity for survival on the road. Now 27, he was born in 1882, although no one remembered where. In the sole surviving photograph of him, taken in Algeria in 1915, Jean-Eugne looks more like the prosperous mayor of a French city than a traveling Gypsy. His dark hair is combed back from his broad forehead above virile eyebrows and the penetrating eyes that dominate his face. His cheekbones are pronounced, his mouth hidden behind the usual mustache, a symbol of masculinity affected by most Gypsy men as soon as they can cultivate one. Dapper in a dark suit, he appears distinguished and, above all, wise from a lifetime of having seen many things in many lands with those piercing eyes. As the Romany proverb went, He who travels, learns.

Basketmaking was labor Jean-Eugne only did when times were tough. He boasted a special talent: Jean-Eugne was an entertainer, another timeless mtier of the Gypsies. He could juggle with the best circus sideshowmen and tease audiences with the mysteries of legerdemain. But Jean-Eugnes pride was in playing musicviolin, cymbalom, piano, guitarand directing a dance orchestra of Romanies. It is this pride that shines in his eyes in the photograph: He is seated at his piano with his band arrayed around him. And while the hands of the musician next to him look like those of a peasant who could be holding a plow as indifferently as they grip his viola, Jean-Eugnes hands are crossed before him in regal manner. Even in this ancient photograph, they look like the fine hands of an artist.

Next page