C ONTENTS

To the victims of January 8, 2011, in memory of Christina-Taylor Green, Dorothy Morris, John Roll, Phyllis Schneck, Dorwan Stoddard, and Gabriel Zimmerman, and in memory of Daniels dear uncles Art Hernandez and Marcos Quiones

D. H. and S. G. R.

F OREWORD

BY DEBBIE WASSERMAN SCHULTZ, MEMBER OF CONGRESS

A LOT CAN BE AND HAS BEEN SAID ABOUT A MERICAN DEMOCRACY . For more than two centuries it has been rightly held up as a model for new democracies and aspiring peoples across the globe who yearn to experience what it is to be free.

We are taught in school that American democracy is about principles: one person, one vote; equal protection under the law; life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. But while the selection of our leaders through a nonviolent expression of the people is a fundamental aspect of our democratic system, it is only the end result of a long process that speaks even more profoundly of the participatory character of our democracy. Ask any president, senator, representative, city councilperson, or school board member how they got to where they are today, and theyll tell you that they wouldnt have achieved their goals without the volunteer help of everyday Americans. Every name you see on the ballot, every candidate at a debate, or any politician you see on TV owes their success in no small part to the passion and dedication of everyday, ordinary Americans.

Each year hundreds of thousands of Americans volunteer for a political campaign, or a political organization, or a ballot initiative. Whether they gather petitions to get a candidate or a cause on the ballot, answer phones in an office, walk door-to-door to promote their candidate, register voters, or work as a nonpartisan poll worker, these volunteers and their countless hours of unpaid work are the backbone of Americas democracy.

Some volunteer because they believe in a person; others volunteer because they believe in their party. Some because they see parallels in a candidates platform with a personal cause or that of a loved one; and some just believe it is their civic duty. Regardless of the motivation, one thing is clear: American democracy would not function properly without them.

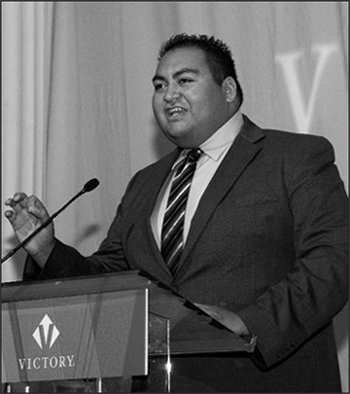

Daniel Hernandez, a veteran volunteer of both Hillary Clintons presidential campaign and Congresswoman Gabby Giffordss 2008 reelection campaign, had signed up in 2011 to once again volunteer for Congresswoman Giffords, this time as an intern in her Tucson, Arizona, congressional office. America got to know Daniel Hernandez as the young intern who rushed to Gabbys side immediately following her being shot that horrible morning. I am eternally grateful for Daniel and everyone who played a role in saving the life of my friend that day, but that is not why I write this foreword.

Much has been written about how Gabby was shot while doing exactly what our Founding Fathers envisioned for a participatory democracy, a forum through which everyday Americans could talk, face-to-face, with their local member of Congress. But gaining less attention was the work of the others who were there that morning, the people without whom Gabby would never have been elected to Congress, nor be able to perform the job of Congressperson. They are the staffers, one of whom lost his life and others of whom were injuredboth physically and mentallyand Daniel Hernandez, who was less than one week into his unpaid internship in Gabbys congressional office. These public servants were simply doing their jobs that Saturday morning, helping Tucsonans meet with their congressperson. Just as Daniels story neither begins nor ends at the shooting in Tucson, neither does the importance of using his story to better understand America.

Anyone who meets Daniel is struck by three things: his confidence, his calmness, and his determination. Yet for too many Americans even today, Daniel, as an openly gay, Hispanic young man, should never have been there that Saturday morning. For them, Daniels sexual orientation and ethnicity disqualify himthey represent something wrong with society, an America that is forgetting its roots. And that is why Daniels storythe complete storyis worthy of reflection.

America, the great melting pot, the standard by which all other democracies are judged, was originally colonized by white men who believed that only white, land-owning men should have the right to vote. Over the centuries, and not without struggle and intense internal debate, America has evolved, and I believe now more fully embraces the spirit of inclusive participatory democracy than could have been imagined at the birth of our nation. Yet change is difficult and, for some, harder to accept than for others.

On Saturday, January 8, 2011, Daniel Hernandez was doing what hundreds of thousands of Americans do every year: He was volunteering for a person that he believed in. But then he did something that we all wonder whether wed instinctively have the courage to do ourselves: He heard gunshots and ran toward them, to help those in need. His actions that day helped to save my friends life and they helped every American see the sharp contrast between the evil displayed by a deranged shooter and the selflessness of individuals who rushed in to help those in need.

Daniels story exemplifies the point that American exceptionalism is rooted in individual freedom and liberty, a notion that welcomes everyone from all paths of life into the American experience. Simply put: excluding Daniel that fateful Saturday wouldnt have hurt him nearly as much as it would have hurt America.

I hope that you enjoy getting to know Daniel as much as I have.

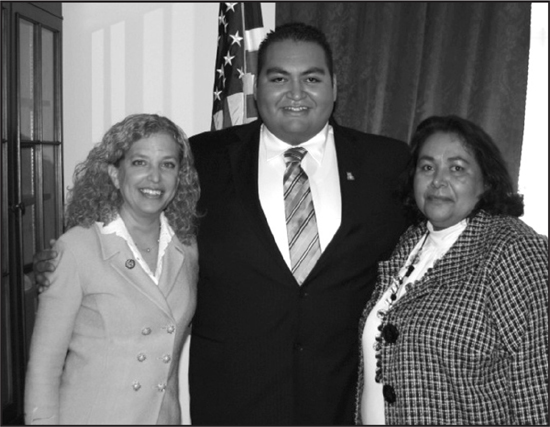

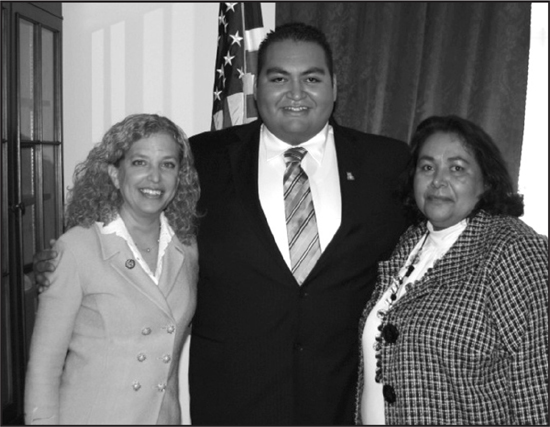

Representative Debbie Wasserman Schultz, Daniel, and Daniels mother in Washington, DC, February 2011

P ART O NE

THE SHOOTING

C HAPTER O NE

SATURDAY MORNING

G UN ! SOMEONE SAID, AND IT CLICKED : I REMEMBERED SOME OF the things that had happened over the past several months. There had been a campaign event where an angry constituent had brought a gun but had dropped it. And the door of Gabby Giffordss congressional office in Tucson had been shot at last March, after the vote on health care. Gabe Zimmerman, Gabbys aide, had come up to me that morning and said, If you see anything suspicious, let me know.

So I heard shots, and the first thing I thought of was Gabbymaking sure she was okay. I was about thirty to forty feet away from the congresswoman. I heard the shots and ran toward the sound.

I dont consider myself a hero. I did what I thought anyone should have done. Heroes are people who spend a lifetime committed to helping others. I was just a twenty-year-old intern who happened to be in the right place at the right time.

T HAT S ATURDAY , J ANUARY 8, 2011, started like an ordinary day. I got dressed in business casual clothes: shirt, argyle sweater, khakiswhat I wear to the office. Gabe Zimmerman had organized a Congress on Your Corner event at a shopping center just north of Tucson. Representative Giffords liked to meet her constituents in person and talk to them about what was on their minds, and discuss what was happening in Congress that they were concerned about. Weeks before, I had applied for an internship at her office, and they had accepted me halfway through the interview. I was supposed to start on January 12, when school was scheduled to begin. Im a student at the University of Arizona and major in political science. But the office was short-staffed, and Id volunteered to start early.

Next page