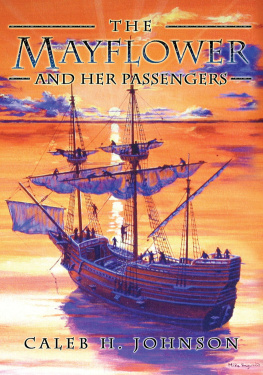

The ship had never carried passengers. She was a freighter, rather old and tired after more than fourteen years of running taffeta and satins from Germany, hats and hemp to Norway, wine and cognac from France. Thanks to the wine, she was called a sweet ship - her hold full of pleasant odors, in contrast to the foul fumes that rose from similar ships of the day. Otherwise, riding high beside her dock at Redriffe on the Thames, after discharging a cargo of wine from Rochelle, France, on May 15, 1620, she was no different from a hundred other square-riggers in this bustling section of London Port.

Down the quay crowded with boxes and barrels and lounging sailors came two men. One walked with a quick uneasy gait, his eyes wary. The second was better dressed and carried himself with an expansive swagger. They stopped before the ship, and the second man called out to a seaman repairing sails on the sunny deck. Ahoy, there. Mayflower of London?

Aye.

Captain Christopher Jones?

Aye.

They were necessary questions. The old ship had a common name. Centuries later, confused historians would count at least twenty Mayflowers in the port records of the era. Two even fought on that historic day in 1588 when the seamen of Queen Elizabeth smashed Spains mighty Armada and made the oceans of the world English territory.

Good Queen Bess was dead now, these seventeen years. Will Shakespeare, her reigning poet, was dead four years, although some of his plays - Henry IV, Othello, Much Ado About Nothing - still did a brisk business for the Kings Men at Blackfriars Theater. But the rest of England was neither prosperous nor content. An utterly different ruler now sat on the throne. Unstable, indecisive James I had done little since 1603 but drain the treasury with his extravagance, shock the nation with his morals, and embitter those who yearned for religious liberty.

Not that King James was any worse, or better, than his times. It was an age of excess. Elizabeth had had a fondness for extravagance, which once inspired the Earl of Hereford to greet her with three thousand footmen fitted out for the occasion with black and yellow feathers and gold chains. Under James, extravagance had become a passion. It was hard to tell Londons fantastically dressed gallants from women. Ladies appeared at court in gowns that cost fifty pounds a yard for the embroidering alone, equal to 7,000 pounds today. The House of Cecil spent over fourteen hundred pounds hanging the bedroom of their Countess of Salisbury with white satin embroidered with gold, silver, and pearls to celebrate the birth of an heir. In a typical year, the king paid out five thousand pounds in benevolences to his favorites.

The manners and morals of the court were appalling. Banquets frequently turned into riots. A Venetian diplomat described one repast at St. Jamess Palace with its usual shoving, brawling crowd. At the first assault, they upset the table and the crash of glass platters reminded me precisely of a severe hailstorm at midsummer smashing the window glass. When the lord mayor of London gave a dinner for the new Knights of Bath, the so-called gentlemen behaved outrageously with the citizens wives. The sheriffs finally broke open a door and found Sir Edward Sackville in such a scandalous position that the entire banquet was forthwith abandoned.

Elsewhere the bucolic merrie England of song and story was rapidly vanishing. One justice of the peace wrote to a friend: It is sessions with me every day all the day long here, and I have no time for my own occasions, hardly to put meat in my mouth. There was yesterday fourteen brought before me and presented that are so fit for no place as the House of Correction, all of one parish.... Unemployment was widespread. The number of poor do daily increase, one commentator wrote, there has been no collection for them, no not these seven years, in many parishes of the land, especially in country towns: but many of those parishes turneth forth their poor, yea, and their lusty laborers that will not work, or for any misdemeanor want work, to beg, filch and steal for their maintenance... until the law bring them unto the fearful end of hanging. Men and women were regularly hanged for stealing as little as a loaf of bread. No one seemed to think twice about it, perhaps because a prison term was also tantamount to a death sentence, either from disease or the brutality of venal jailers.

It was an uneasy society, racked by vast changes in money, morals, and religion, with the last by far the greatest. Martin Luthers protest had sent a shock wave rolling through Europe. In country after country, rulers were struggling to control alarming new impulses toward personal freedom and spiritual independence. Perfectly logical, from a royal point of view. If a man was free to choose his religion one day, the next he might feel free to choose his king.

But the publication of the Bible in the vernacular had unleashed a power that no king could control - and no nation had taken to this new freedom more eagerly than England. Theology rules here, said one visitor shortly after Elizabeths death. The scandals of King Jamess court only convinced more and more people that England needed a deep infusion of Biblical religion if the nation was to survive. From secret printing presses in Scotland, Holland, and Switzerland, Bible-inspired books and tracts poured into the country year after year urging reform in the English Church as a first step to reforming a corrupt crown.

Others, despairing of reform, urged separation from the English Church and the right to join independent churches where men could worship as their consciences directed them. This was even more dangerous doctrine, and against these Separatists the royal fury was unchecked. Informers, sheriffs, constables, and bailiffs were under orders to harry them out of the land.

Captain Christopher Jones of the Mayflower had no interest in such arguments. He was a solid, steady, respectable businessman of fifty with a wife and two children ashore and a one-fourth interest in his ship to guarantee his prosperity. Besides, he had spent most of his life at sea, more interested in reading charts and compasses than the Bible. Born in Harwich, the son of a prominent sea captain, he was hardly the sort of man to become involved with religious extremists. But the two men who greeted him in his comfortable Great Cabin on this lovely June day had a business proposition that was deeply involved with Englands explosive religious dilemmas.

Robert Cushman was the name of the first man. He was mild mannered and nervous and described himself as a wool comber from Canterbury. The second man, bluff, hearty, full of jokes and good nature, did most of the talking. He was Thomas Weston, an ironmonger by trade but quick to make it clear that his money spoke for him in a dozen other businesses.

Weston was a born promoter and described in glowing terms the plans that he and some London friends had for starting a plantation in North America. Over seventy merchants and gentlemen were prepared to put up seven thousand pounds to launch a joint stock company for the venture. They would avoid all the mistakes that had turned Jamestown, Virginia, into a costly fiasco yet to show a cent of profit after thirteen years of toil. Mr. Cushman was acting here as the representative of the prospective planters - sober, industrious Christians now sojourning in Holland because they disliked the kings religious conformity and wished to stay out of his majestys jails. They had a royal patent for a tract of land on the American coast. All they needed was a ship. Would Captain Jones be interested?