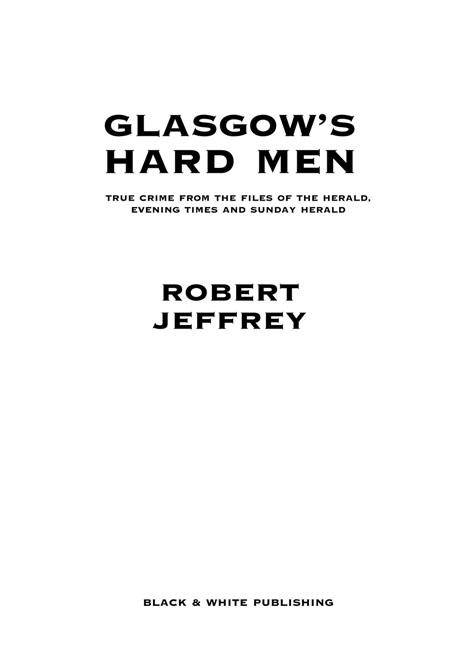

This book could not have been written without the work of countless Herald-group journalists down the years. Dedicated feature writers, big-name columnists, photographers and hard working anonymous rota reporters have produced one of the worlds great archives. They conducted the interviews, reported the murders, arrests and court cases down the years. Every facet of life in Glasgow and its surrounds over the last 200 years has been faithfully chronicled. From these files have been culled some of the great stories of the battle against crime in the city.

I would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Marie Jeffrey, Samantha Boyd, Jackie Borrett, Kingsley Borrett, Ian Watson, John Watson and the staff of the SMG Publishing Division library: Stroma Fraser, Pip Ryan, Jim McNeish, Maris Thomson, Kathleen Smith, Natalie Bushe, Angela Laurins, Malcolm Beaton, Sara Stewart, Tony Murray, Eva Mutter, Catherine Turner, Lisa Turner and Grace Gough.

CONTENTS

Travelling abroad around 30 years ago, in the heyday of the package holiday, many a Glaswegian habitually disguised their roots. Where are you from? That was a standard hotel bar opener as the first Cuba Libres slipped speedily over throats parched by the Majorcan sun and with the annual fortnights escape from the tyranny of shipyard or steelworks stretching thirstily ahead. Holidaymakers from Govan, Garthamlock or Garngad tended to mumble a reply about the West of Scotland, or Lanarkshire or whatever. Anything for an easy life. To admit upfront to the Sassenach hordes that you were a gold-plated Glaswegian could provoke an ill-informed suspicion that you had left an open razor handy in the bedroom drawer, or that your days in the sun had been financed by unauthorised withdrawals from the handbags of dear old ladies.

Such was the worldwide misconception about Glasgow in the days when the image of No Mean City Alexander McArthurs controversial and often misunderstood novel depicting the pre-Second World War gangs and gangsters ruled and the Glasgow Smiles Better campaign, the Garden Festival and European City of Culture were distant dreams. It is hard now in the dawning days of the 21st century to realise how potent that image was to folk who had never crossed Glasgows city boundary.

It was a different story for those who grew up in a place that was often unfairly called the Chicago of Europe, or accused of making Marseilles look like a garden suburb. Knowledge of the citys deep-rooted image in the collective consciousness of most of the world was hard to avoid. Sometimes it was simply the menacing strut of some young gang member seen fleetingly in the street. Or it could be much worse.

As a youngster growing up in the sheltered streets of Croftfoot a south-side suburb of tidy, rented, four-in-a-block houses with gardens in front and a normally well-kept drying-green at the back big-time crime was not normally overly visible, even if the local ironmonger did a good trade in chains and padlocks for bicycles. Croftfoot and Kings Park, its slightly more upmarket neighbour, had their own leafy park and even a nice little nine-hole golf course set on a steep hillside a course that had been memorably described in a series of newspaper articles by the famous amateur golfer turned sportswriter, Eddie Hamilton, as a place where the biggest advantage one golfer could have over another was to have one leg shorter than the other.

It was to such wide open places that youngsters from less prosperous areas like nearby Bridgeton tended to roam looking for trouble with the suburban kids. One day my school pals and I found ourselves in a minor rumble with a group of Brigton boys who told us proudly that they were members of a gang called the Biro Minors. This undeniably witty title reflected the fact that they thought their peers were the infamous Bridgeton Pen Gang, the original Biro Minor being the then innovative ball-point pen. The Croftfoot boys were suitably and speedily impressed and fled to their mums, an early introduction to the continuing heritage of No Mean City.

Childhood visits to an aunt originally from Armagh, a place that is no stranger to violence, brought other tales of Bridgeton in the days before the legendary Chief Constable Percy Sillitoe The Captain to his men took on the gangs and helped to begin the slow claw-back from the image of the razor slashers and gangland warfare that, no matter how often it is denied or described as exaggerated, stuck to Glasgow for too many years.

Starting work as a journalist in the 1950s, Glasgows image of a tough place to live and work was further defined. The papers themselves relied heavily on crime to sell. At the top end of the scale there were undignified scrums outside the High Court as rival hacks fought to buy up the stories of participants in major trials. Criminals who had never ventured more than a couple of miles away from a spit-and-sawdust howff and the booze-swilling company of their foul-mouthed mates were whisked to four-star hotels to spill the inside story of their misdemeanours over a bottle of malt. With a nice cheque served with breakfast the next morning.

The most memorable of these street battles was the occasion when famous Glasgow underworld figure Walter Scott Ellis was freed on a charge of murdering a taxi driver. He was said to have been bought up by one of the citys morning newspapers, but was bundled into an Evening Citizen car in a skirmish. At the height of this mini-riot it was said that a man with a broken leg was flaying out at all and sundry with his crutch. This event, notorious in newspaper history, led to a judgement by Lord Clyde on how cases in Scotland should in future be handled by the Press. Although modified over the years, the strictures imposed by this case still affect how newspapers deal with police investigations to this day. And of course, these days the Press Complaints Commission has a strict policy on not allowing criminals to benefit financially from their crimes though this self-regulation has its critics and there is on-going argument about the definition of financial benefit.

At the other end of the crime-scale, stair-heid rammies and minor feuds were reported in great detail. These were the days of hot-metal journalism with the popular papers heavily staffed with crime reporters, a breed who spent their proprietors cash with abandon building up the allegedly vital contacts book. The old joke was that some of the best had such good sources for tip-offs and contacts that they could not write about them for fear of exposing the source! The stories they did get into print were sub-edited by veterans, often ex-reporters who had come off the road to settle for a warm desk and the comfort of a bottle of Scotch in the bottom drawer as they crafted the eye-catching intro and headline required by editors with an eye on circulation. One of my first jobs was on the now defunct Bulletin, and on my first night in the then Buchanan Street printing plant one such wise old sub-editor asked me where I stayed and how I planned to get home. He gave me a gem of advice for my early morning stroll back to the southside always walk down the middle of the street as this gives you 10 or 12 yards start on assailants emerging from close-mouths.

But even in this sort of Glasgow it was, as always, a war with two sides. The newspapers who so carefully chronicled the gangs, the robbers and the drug barons also had a cast of heroes. Particularly the cops. The city needed tough Chief Constables and they had a succession of them from Sillitoe to Robertson to McNee and many others men who wrote themselves into the citys history as hard as anyone on the other side of the crime divide. The PC on the beat in Glasgow has always had an unenviable job, but at least they have the satisfaction of being led by Big Men. A cynic might remark that the exploits of the police created as much interest and sold as many papers as the crimes of the gangs The Billy Boys, the Norman Conks, the Baltic Fleet and all the rest of the villains.

Next page