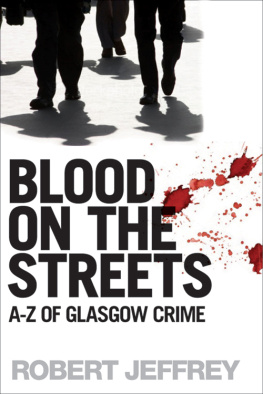

CONTENTS

The Case of Madeleine Smith

The Case of Jessie McLachlan

The Case of Dr Edward William Pritchard

The Case of Oscar Slater

BY ROBERT JEFFREY

It is remarkable that in the dawning days of the twenty-first century Jack Houses tales of murder most foul in Victorian/Edwardian Glasgow are as fascinating and fresh as when they were first written. But not surprising. Square Mile of Murder is only the best known of more than seventy books by the man many consider to be the greatest journalist Glasgow has ever produced.

Ironically, another candidate for that title, Cliff Hanley, once indulged in a little good-natured semantics claiming that Jack wasnt a true Glasgow keelie at all.

According to Cliff, Jack who grew up amid the wally closes of Dennistoun was actually born in Tollcross when it was an independent burgh in the days before Glasgow started to swallow up its small neighbouring towns. But Cliff was always a true disciple of Jack House. In an article published in the Evening Times entitled The Man Who Was Mr Glasgow immediately after Jacks death in 1991, he wrote that Jack had a marvellous way of seeing the mundane aspects of the city from angles nobody had ever thought of and turning them into marvels. Cliff wrote:

Glasgow has always had its pride, of course, workshop of the world and all that. But with it went an inferiority complex, the slums, the diseases, and the suspicion that we were basically scruff.

It is no exaggeration to say that Jack, more than any other individual, got rid of that. For me and not only for me, he brought the place vibrantly to life and I developed a desperate desire to walk in his footsteps.

Jacks death brought forth tributes from people in all walks of life. The legendary curator of the Peoples Palace, Elspeth King, told the newspapers that he had been a living reference book on Glasgow and that his knowledge was indispensable: Perhaps his greatest contribution was his fight to preserve the citys old buildings before that was fashionable. But the ordinary folk in the street mourned his passing in an extraordinary way as well, for he was known to thousands of his fellow citizens in a manner not possible today.

Jack liked pub life; reporting was a drouthy job, he often claimed. He ate out almost every night, often in his favourite Italian restaurants, and was a genuine gourmet and a connoisseur of the well-made gin and tonic. He didnt drive a car and loved travelling by tram. Indeed, when the last tram bent the last penny left on the rails on its way into history in 1962, he wrote, The Glasgow I knew ceased upon the midnight hour when the last tramcar ran through the town.

Conductors, drivers, passengers, street-corner newspaper vendors, everyone knew Jack, for when not on his beloved trams he walked the nooks and crannies of the city with a ready word for everyone. His distinctive appearance and the way he seemed to be just around every corner, especially in the West End, made him the most recognisable figure in town.

At one stage in my life in journalism I shared an office with Jack and that meant the occasional halt in work for a stimulant. Everyone in every bar wanted a word with Jack and they mostly got it in a good-natured way. He was a hugely entertaining conversationalist with a great sense of humour. He often told of his early days as a hack when he would repair with his cronies to the old Cairns howff at the corner of St Vincent Place and Buchanan Street. To Jack and his pals, this became the Eastern Club because it was then opposite the prestigious Western Club which boasted a very different clientele of assorted toffs.

Although the ultimate defender of Glasgow, he was no hater of the capital and enjoyed visiting it. Indeed, on occasion he walked through to Edinburgh, though it is said he had more of a spring in his step on the way home.

He had left school in the days when you took the job your parents wanted for you and started out in life as an unlikely apprentice to a chartered accountant. He soon escaped into journalism and a lifelong interest in crime and the reporting of it was no doubt fostered in his days as a court reporter, when he was remembered as a brilliant note-taker with immaculate Greggs shorthand. In those days Glasgow had three evening newspapers Times, News and Citizen, in the cry of the vendors and in his day Jack worked for all three.

Strangely, it was claimed that some early editions of Square Mile of Murder contained untypical errors in the recounting of the false accusations against Oscar Slater, and these errors led to confusion over the name of the real killer. Jack was always particularly fascinated by the Madeleine Smith story and on occasion returned to it. Her trial had been an astonishing tale of passion, poison and deception on a grand scale. Jack was convinced of her guilt. After winning a not proven verdict a verdict that to this day is the most controversial in Scottish law she moved to London and became part of the socialist society. She mingled with the likes of George Bernard Shaw, George Webb and Karl Marxs son-in-law Edward Eveling, seemingly unfazed by her notoriety. She moved to America to be with her son Tom in 1916 and died in the Bronx in 1928.

Some years before her death according to no less a source than Somerset Maugham she admitted she had killed Pierre and in the same circumstances would do it again. Despite this, fascination in the case remains so strong that, as late as 2000, the theory that LAngelier had supplied the arsenic and had plotted to make Madeleine seem guilty still had support. Such a juicy murder lends itself to endless speculation!

Jack Houses writing career began in 1924 with the payment of a guinea for a 500-word story for Blackies Childrens Annual. His first book, Eight Plays for Wolf Cubs he was a great supporter of scouting was published in 1927. But after his early days as a court reporter, he concentrated on feature writing and became the foremost chronicler of his city. Towards the end of his marathon career he died at eighty-four, battering his typewriter almost till the end he was much honoured by his city and his peers.

Inevitably, he won the St Mungo Prize, the ultimate accolade the city has to offer. It was the mark of the man that his innate modesty meant he could truthfully tell the reporters who flocked to interview him when the news broke that, I never thought for one single moment that I would be selected. To tell you the truth when the chap called and told me I was so completely taken aback I said, Excuse me one minute. I am going to have to sit down. To Jack, it was the second and biggest surprise of his life. The first was getting the honorary degree of Doctor of Law from Glasgow University. That was traumatic enough. Perhaps this is even more so.

It was all a deserved accolade to a career full of highlights and not without controversy. Although at one time he had had strong connections with the Church of Scotland, he was no fan of Billy Grahams hell-fire evangelism. When barely a voice was raised in criticism of Graham at his first crusade in Glasgows Kelvin Hall in 1955, Jack described the famous American as looking like what he is, a super insurance salesman. He further claimed on national radio where he was quite a celebrity that the illegitimate birth rate often rose after such evangelical campaigns.

Jack took celebrity in his stride. In the Second World War he started as an infantryman in Aberdeenshire but ended up in the Army Kinematograph Service as a scriptwriter, with Lance Corporal Peter Ustinov as a colleague and David Niven as his colonel.

But right after the war it was back to the old Evening Citizen and the feature writing beat. He travelled the world to Russia, America, Bali, Bangkok, Singapore, Mexico, Africa and most of Europe. He said it was as if you were being paid to enjoy yourself and remarked, I could hardly have done better if I had been a football reporter.