Sarah Andrews

IN COLD PURSUIT

To the good people of McMurdo Station, Antarctica

and some of the bad ones, too

THIS MATERIAL IS BASED UPON WORK SUPPORTED BY THE National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0440665. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

My sincerest thanks go to the National Science Foundation Office of Polar Programs for their support of science education and outreach. It was through NSFs Antarctic Artists and Writers Program that I traveled to the locations depicted in this book to do the research necessary to bring to the page this story and the descriptions of scientific research and discoveries it conveys. In particular, I wish to thank Marilyn Suiter, who first invited me to speak at NSF; Guy Guthridge, who invited me to apply for an AAWP grant; Kim Silverman, who picked up where he left off; Julie Palais, who connected me with glaciology programs; Tom Wagner, who connected me with geology programs; and Dave Bresnehan, who managed McMurdo Station while I was there.

This is not a work of science fiction, which is a genre characterized by what if? questions posed by either suspending certain facts of science or by projecting future occurrences based on not-as-yet-invented technology or not-yet-discovered features of nature. Instead, I write fiction about science, which presents fictional characters but actual scientific findings, or events of nature that are within the bounds of what would actually occur at a given location. Thus the scientific research and findings presented in this book are borrowed from current science events, but the scientists have been replaced by fictional characters and situations, and, need I say, no one was actually murdered in the creation of this book.

I am deeply indebted to Kendrick Taylor and Noel Potter for their technical input and for reading complete drafts of this book while it was in preparation. Todd Hinkley of the National Ice Core Library kindly tutored me on the care and interpretation of ice cores, David Ainley vetted the penguin bits, Gary McClanahan corrected the tractor scenes, and a great many others kindly responded to a hail of e-mails, there always being one more detail I needed to get just right. These people include Neal Pollock, Sam Bowser, Matt Huett, Jim Mastro, Ted Scambos, Mark Fahnestock, Ashley Davies, Dorothy Burke, Nicole Bonham Colby, Kristeen Dewys PA-C, Eric Junger, and Maureen Bottrell. Eileen Rodriguez once again corrected my hideous and confused use of Spanish. Richard Alleys The Two-Mile Time Machine: Ice Cores, Abrupt Climate Change, and Our Future was a key published resource in the growth of my understanding about climate as interpreted from ice cores.

It has been my pleasure to have assisted many fine geologists in honoring James W. Skehan, S.J., Professor Emeritus, Director Emeritus, Weston Observatory, Boston College, by naming a character after him in this book. I thank R. Laurence Davis, Kate L. Gilliam, Helen Greer, Arthur Mekeel Hussey, Noel Potter and Helen Delano, Paul Karabinos, Priscilla Croswell Grew and Edward S. Grew, Christopher Hepburn, and good old Anonymous for contributing considerable funds to the Geological Society of America Foundation to establish this honor.

Before I deployed to Antarctica to research this book, a great many people coached and assisted me in preparing my field plan. Primary among them were Christine Siddoway, Stewart Klipper, and Karl Kreutz. I gleaned essential understandings from research papers presented at West Antarctic Ice Sheet Workshops in 2005 and 2006, which were ably run by Robert Bindschadler of NASA.

Once in McMurdo Station, I received key scientific inspiration and guidance from Kendrick Taylor, Karl Kreutz, Christine Foreman, Douglas MacAyeal, Nelia Dunbar, Phil Kyle, Kathy Licht, and Sam Bowser.

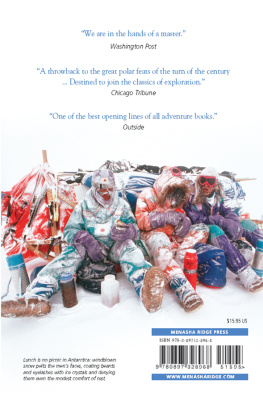

The good people who support McMurdos infrastructure were also keys to the success of my visit. Being a part of that great army that travels on its stomach, I wish to thank all the Raytheon Polar Services personnel who worked so hard to serve three incredibly delicious meals per day under the superior guidance of Sally Ayotte. Trevor and Erik had us eat freeze-dried sludge with chocolate bar chasers at survival school, but I thank them as well. I am grateful to the personnel at Berg Field Center who stocked such warm sleeping bags, snug tents, and leak-proof pee bottles, and those at Science Support Center who taught me to drive a Pisten Bully. Thanks go to the fine pilots and personnel of Helo Ops who got me where I needed to go (especially Paul Murphy, who let me use his name, and Melissa, who always had a smile), and the staff at Crary Lab, most especially Micheal Claeys, who sustained me with hugs. Thanks also to Peter Somers, Barb Wood, Jean Pennycook, John Wright, Mariah Cross-land, and Cara Ferrier, and thank you, Warren Dickinson, for showing me around Scott Base. McMurdo runs on the backs of all those who sweep the floors, drive the shuttles, maintain the shops, recycle wastes, generate power, purify water, and process sewage; though your acts may seem humble, they were essential in creating the environment in which research can be done in a forbidding environment. There are perhaps one thousand people I need to thank, such as Holly, who kept my computer running, and the marvelous man whose name I didnt get who gave me a disc of his favorite photos, so THANKS TO ALL OF YOU!

Field deployment in Antarctica is not undertaken casually, and many people worked hard to keep me safe while they tried to educate me; moreover, they made room and time for me during the incredibly hectic schedules Antarctica squeezes from its researchers. For teaching me about ice on Clarke Glacier, I am indebted to Karl Kreutz, Bruce Williamson, Mike Waszkiewicz, Toby Burdet, and he who prefers not to be named. On Cape Royds, I could not have had better teachers about penguins than David Ainley and Lisa Sheffield, and am indebted for archaeological information about early explorers to Neville Ritchie, Alasdair Knox, Robert Clendon, and Doug Rogan, representing the New Zealand Heritage Trust. In Arena Valley, I wish to thank Jaakko Putkonen, Greg Balco, Daniel Morgan, Bendan ODonnell, and Nathan Turpen.

Scientific field work was not the only Antarctic field deployment that informed my research. For the great kindness of sending me on a traverse to Black Island Station, I wish to thank Fleet Operations director Gerald Crist; traverse foreman Katrine Jensen; Gary McClanahan, who taught me to drive a Challenger 95 and kept me smiling; Ron Rogers, who taught me to drive a certain Delta named Flipper; and James, who showed me how to hurl flags off the back of Flipper. At Black Island, I could not have been in better hands than those of station manager Tony Marchetti and cook Jessica Gonya.

The fixed-wing aircraft of Antarctica and their personnel were wonderfully generous with me, taking time to teach me about their aircraft, the navigation and cargo transport thereof, the trapping of nonexistent rodents, and the fine art of inventing fun in the Coffee House (Tractor Club membership being free, life-long and irrevocable). I wish in particular to thank Colonel Ron Smith, USAF JTF / CD Support Forces Antarctica, and Colonel Max Della Pia, Majors Samantha East, Dave Panzera, Mahlon Hull, and Marty Phillips, and Master Sergeant John Rayome of the New York Air National Guard 109th Airlift Wing. I wish also to thank the USAF captain who let me onto the flight deck of the C-17 flying south (name lost with a missing notebook) and Flight Lieutenant Chris Ferguson, Flying Officers Kane Stratford and Leigh Foster, Sergeants Natti Hodges and Steven Knapton, and Squadron Leader Stu Balchin of the Royal New Zealand Air Force, who let me stand in the cockpit flying north rather than die of discomfort in the cargo section of that plane. It was over their shoulders that I watched the long, white cloud of Aotearoa slide over the horizon.