Part One1, from ON THE ROAD by Jack Kerouac, copyright 1955, 1957 by Jack Kerouac; renewed 1983 by Stella Kerouac, renewed 1985 by Stella Kerouac and Jan Kerouac. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

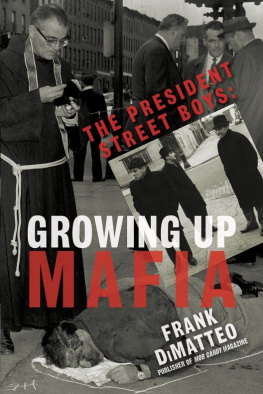

Joey

King of the Streets

Written by Bob Dylan and Jacques Levy

Copyright 1975 Ram's Horn Music. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Reprinted by permission.

Let Me Die in My Footsteps

Let me die in my footsteps Before I go down under the ground.

Copyright 1963; renewed 1991 Special Rider Music. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Reprinted by permission.

Copyright 2008 Mad Ones Corp.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the Publisher.

Weinstein Books

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

ISBN: 978-1-602-86103-9

To the Revolution

The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn.

JACK KEROUAC

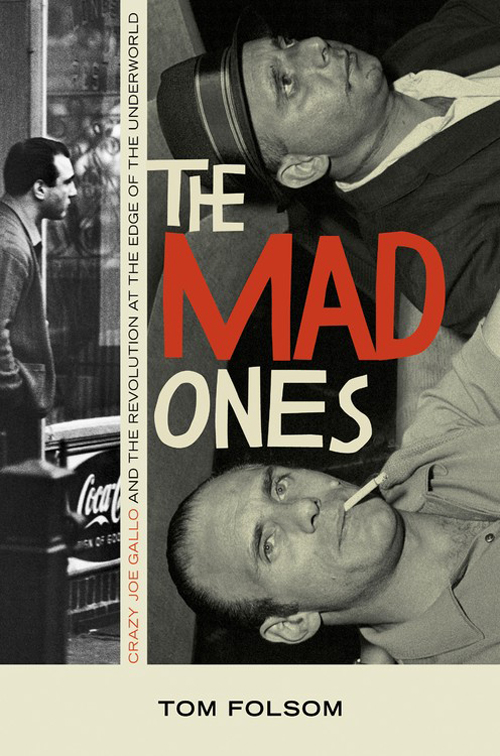

New York City is cleaner and safer now than it was when Crazy Joe Gallo got gunned down in front of Umbertos Clam House on Mulberry Street in the early hours of April 7, 1972.

Joeys world was cigarette-fogged nightclubs on the East Side. Gangland killings in the barbershops of ritzy hotels. Dingy pads in jazz-fueled Greenwich Village. He dressed in spit-shined Italian loafers and skinny black ties. He rode in a 1955 Cadillac and ran the jukebox racket. He and his brothers holed up with shotguns in a dilapidated tenement on the crooked South Brooklyn waterfront and waged guerrilla war on the desolate streets of Red Hook.

The tale of the Gallo brothers has been recounted in the lore and legend of New York City, including Bob Dylans ballad, Jimmy Breslins comic novel, and fictionalizations in The Godfather trilogy, but I felt that no non-fiction book captured the madness of the Gallos. I had to recreate his world to understand why he did what he did. I read what Joey read and studied his heroesthe strangers in Camus, the outsiders in Sartre. I pieced together a case dragged out from half a century ago. I interviewed those who had been on the scene firsthand. I waded through almost 1,500 pages of unpublished FBI files on Joey Gallo and culled what made sense from the least reputable sources: Wiretaps of underworld conversations. Leads from informants.

In order to reconstruct the narrative in a fast-paced, as you are there immediacy, I was forced to choose between multiple and contradictory versions of past events, some that could only be verified by the victims. Three books I kept within reach included one of the best cop books to come out of the mean streets of New York City, Chief, by Albert Seedman, Inspector Raymond Martins Revolt in the Mafia, and Donald Goddards Joey, filled with interviews from the women left behind in the wake of Crazy Joes murder.

None of the dialogue has been made up.

Names have been changed to protect the innocent and preserve the reputations of the dead.

The body rested comfortably in tufted velvet eggshell, dressed in a double-breasted navy blue pinstripe suit with a dark blue shirt and deeper blue polka-dot tie. A bouquet lay below the folded hands, right over left, the right ring finger decked out in a large square blue stone. A gold cross and chain hung around the neck. A lithograph of Jesus hung on the bright pink curtain behind the bier.

Carmella knelt beside the bronze coffin at the private family viewing in the baroque Morgan Room, paneled in dark wood with ornamental wallpaper. Dim chandeliers hung from the high ceiling. Among the wreaths of red roses, orchids, and yellow and white chrysanthemums, a book made of flowers lay open on a stand, spelling out in petals, To My Brother, Joey Gallo.

For nearly an hour in the funereal quiet, Carmella stroked her brothers slicked-back hair and kissed the mole on his cold cheek. Joey couldve taken the Gallos to greatness in a dynasty to match the Kennedys. The papers wrote only the bad things about him, but Carmella knew the possibilities, cut short by a hail of bullets at Umbertos Clam House in the heart of Little Italy.

Blood in the streets! screamed Carmella. The streets are going to run red with blood, Joey!

Joeys mother, Mary, fainted. She wore old-country black. Four young men carried her downstairs to the basement parlor of Guidos Funeral Home, a Greek Revival brick mansion built by robber barons. Someone held smelling salts under her nose.

My Joey, my Joey, what did they do to my Joey? What did they do to my Joey?

The night before, a doctor had been sent to Marys wood-frame, asbestos-shingled rooming house in a rundown section of Flatbush to administer tranquilizers. He walked in and saw a bunch of guys standing around. He was told not to say much.

What happened to her son? asked the doctor.

He had an accident, said one of the guys.

Marys portly and bald seventy-one-year-old husband now sat on a chair in the corner of the funeral parlor.

Hes all right, remarked an onlooker. Dont worry. Hes been ready.

According to an FBI informant, Umberto, the bootlegging father of the three notorious Gallo brothers, raised his sons to be hoodlums and killers, encouraged them in their criminal activities, and influenced them to remove all competition in their illegal enterprises. His eldest, Larry, was buried with a thick purple ring around his neck, seared into his flesh by a manila cord. The baby of the family, Kid Blast, was the last living son. Handsome, with thick muttonchops down his cheeks, Blast dutifully attended to his grief-stricken mother. Mary cursed at a woman whispering consolation in her ear and renounced the heavens, shouting, Jesus Christ? Jesus Christ? You know I dont believe in Jesus Christ!

On this clear blue Sunday in South Brooklyn on April 9, 1972, two hundred mourners filed into the Morgan Room to say goodbye to Joey.

Jacques Levy, the shaggy-haired director of the madcap off-Broadway play Scuba Duba, stood before the bier. Years later, during a late night with Bob Dylan, Levy would recount this sad day when sitting down to write Joey, an eleven-minute ballad on the flip side of the Hurricane Carter story on Dylans album Desire.

I never considered him a gangster, said Dylan of Joey. I always thought of him as some kind of hero in some kind of way. An underdog fighting against the elements. Dylan crowned his eponymous hero King of the Streets, nobler than the fool in The Gang That Couldnt Shoot Straight, the gangster farce by hard-boiled newspaperman Jimmy Breslin. Inspired by the Gallo gang, the novel featured a band of ragtag crooks led by Kid Sally Palumbo, played in the film version by the citys favorite lanky actor, star of stage and screen, side-burned Jerry Orbach.

Orbach made his name over a decade before playing El Gallo, the bandit star of the hit musical The Fantasticks. Looking down on his dead friend, he couldnt help but regret playing Joey as such a bumbling idiot in The Gang That Couldnt Shoot Straight.

Breslins book had portrayed Joey as a clown, Orbach told Time magazine. Then when I met Joey, I was absolutely amazed to find out that maybe he had been a wild kind of nut before he went to prison, but something had happened to him inside.