ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

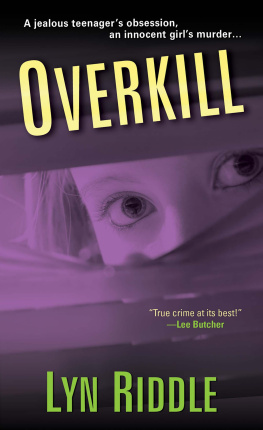

Some years ago, when I was writing newspaper stories about the young mother who drowned her two sons in a Union, S.C. lake, the womans mother said something I have never forgotten. Why has one familys tragedy become a nations entertainment? she asked. I had no answer. Her words come back to me with great regularity as I write more newspaper stories and as I write books about crime. The question makes me think of respect for the dead, but most especially for the living.

I heard those words clearly as I sat in the living room of Hazel Shows home in East Lampeter Township, Pennsylvania, just steps from the spot where her daughter was slain, as she recounted that day and the days that followed. She told me stories she had told no one before. For that I am grateful and feel much responsibility.

I feel deep gratitude as well for John Show, Lauries father, who was willing to share his sorrow yet again so his daughter will not be forgotten. To the members of the East Lampeter Township Police, especially Lt. Renee Schuler, much thanks. They were swept up in nothing less than a tidal wave of criticism for the way they did their jobs, a tumult that caused deep hurt and worry. And yet, they were willing to go back to their memories for the sake of truth. Tabbi Buck was most helpful as were many members of her family. And the Yunkins, Barry and Jackie, provided invaluable insight into the lives of their son and his former girlfriend.

Thanks, too, to my agent Frank Weimann and my editor at Pinnacle, Karen Haas. They are the most patient people on the planet.

To my friend, fellow writer, and best critic, Jamie Jones, deep respect and appreciation. And to my children, Josh, Lauren, and Colin, unending and unconditional love.

Hazel and John Show have taken lifes worst shot, the unnatural course that unfolds when a child precedes parents in death. They placed one foot in front of another and somehow got through the days of the past decade. It has not been easy. They are heroes, deserving a telling of their lives that is honest and true, one that shows respect, not sensationalism. I hope this meets that test.

Simpsonville, South Carolina

September 12, 2000

UPDATE

The thirty-minute drive to Laurie Shows grave takes Hazel Show past Conestoga Valley High School, the same route she drove that morning in 1991. The grave at Bridgeville Evangelical Congregational Church is about fifteen miles past the school. Her parents and sisters are buried there, too, and Hazel makes the drive often. She takes flowers.

I go there and talk to family, Hazel said.

December 2011 marked the twentieth year since Laurie died. At sixty years of age, Hazel makes it known that her daughter would have been thirty-six. Those years have been filled with lawsuits, appeals, motions, and rulings. From the time Judge Stewart Dalzell set Lisa Michelle Lambert free, until the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear Lamberts appeal in June 2005, Hazel and John Show, Lauries father, have lived with an unsettling ambiguity. No less than thirty-five motions and court rulings followed Lamberts 1992 conviction.

At least once a year, they have trudged to a Pennsylvania courtroom to hear once again the details of their daughters death and Lamberts allegations that prosecutors had engaged in dirty deeds and had stripped Lambert of her constitutional rights. The case went from state court to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to the United States Supreme Court and back again.

In September 1999, Christina Rainville and her husband, Peter Greenberg, who were Lamberts attorneys, filed an appeal of Judge Lawrence Stengels ruling with the state superior court.

The next December, Judge John T. Kelly denied the appeal. Coincidentally, the ruling was recorded on the ninth anniversary of Lauries death. The judge said Lamberts attorneys had missed the filing deadline established by Pennsylvanias Post Conviction Relief Act and they were wrong to have first pursued an appeal through the federal court system.

In March 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case. But in November of that year, Dalzell reinstated his opinion that Lambert was innocent. He issued an opinion that ran thirty-one pages and again claimed Lambert had been a victim of wholesale prosecutorial misconduct.

Virtually all of the evidence which the commonwealth used to convict ... was either perjured, altered or fabricated, Dalzell wrote.

The outcry was swift from Lancaster residents, who could not believe the ten-year-old case had not been decided. The attorney generals office sought Dalzells removal from the case four times, before Dalzell finally removed himself.

Judge Anita Brody heard oral arguments in Philadelphia in January 2003. The Shows attended the hearing, which took place on the day after what would have been their daughters twenty-eighth birthday.

Lambert alleged 157 instances in which the prosecution took part in misconduct. In her ruling Brody reiterated Lamberts claims in the following general way: false evidence, fabricated evidence, intentional withholding of exculpatory and favorable evidence and disowning of evidence used to convict her.

Lambert also claimed experts would have testified that Laurie Show could not have spoken because her carotid artery was cut.

In April 2003, Judge Brody ruled against Lambert. Prosecutors had not manufactured evidence or kept information that could prove Lambert innocent from her attorneys. And, most important to Hazel Show, it was possible for Laurie to have uttered, Michelle did it.

Brody wrote: I fail to see a constitutional violation based upon Lamberts assertions regarding the experts. Brody said as an appeals court judge it was not within her purview to rule on whether Lambert was actually innocent, as Judge Dalzell had claimed.

But, Brody said, if she were to offer an opinion, it would be that Lambert is, in fact, guilty. She concurred with the state court, which ruled: There is no question that Ms. Lambert is not, and never will be, innocent of this crime.

In October 2004, the U.S. Court of Appeals in Philadelphia upheld Brodys ruling, and the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case in June 2005.

Rainville declined to talk about Lambert, the case, or the appeals. In the years since she represented Lambert, Rainville worked as a lawyer for the Securities and Exchange Commission and then as a prosecutor in Bennington, Vermont.

In 2007, Angus Love, executive director of the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project, represented Lambert in suing the administrators of the prison at Cambridge Springs in Pennsylvania for not properly overseeing guards who raped her. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania settled the case for $35,000, which, after legal fees, would go to Lamberts daughter, Kirsten, who was eighteen in 2011.