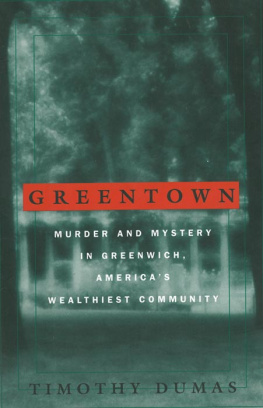

GREEN TOWN

GREEN TOWN

MURDER AND MYSTERY

IN GREENWICH,

AMERICAS

WEALTHIEST COMMUNITY

SECOND EDITION

TIMOTHY DUMAS

Copyright 1998, 2011, 2013 by Timothy Dumas

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Second Edition

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-61145-708-7

Printed in the United States of America

For Maria, and for my mother and father

In truth, all through the haunted forest there could be nothing more frightful than the figure of Goodman Brown. On he flew among the black pines, brandishing his staff with frenzied gestures....

Nathaniel Hawthorne,

Young Goodman Brown

Preface to the Second Edition

I WROTE Greentown fifteen years ago, when the murder of Martha Moxley was a story without an end, a mystery that deepened and ramified with age. That lack of resolution struck me, in those years, as gloomily fitting. For embedded in this story of the savage killing of a teenage girl was a social allegory about power and money out-dueling the puny forces of justice.

Today the better allegory seems to be that of the tortoise and the hare. On January 19, 2000, nearly a quarter century after the murder, Michael Christopher Skakel traveled from his home in Hobe Sound, Florida, to police headquarters in Greenwich, Connecticut, and surrendered himself to the authorities. Not that he was admitting guilt. He never didat least not publicly. The idea was to leave Florida ahead of the state police, who were converging on his house with handcuffs at the ready. By turning himself in, at least, he could then face the world with the dignity of a man presumed to be innocent.

I was there that day, and I saw it all go awry. At age thirty-nine, Skakel had grown heavy, with a round, florid face and thinning, ginger-colored hair. He was dressed in a navy blue blazer, a light blue shirt, and a blue-and-white patterned tie. Between the blazer and the shirt he wore a high-collared yellow sweater. For all anyone knew, Skakel had received the sweater for Christmas twenty-five days prior, so he must have been astonished to learn that by wearing it to Greenwich hed committed one of the great fashion blunders in American criminal history. Somehow the yellow sweater looked like an ascot, Mickey Sherman, Skakels defense attorney at the time, told me. It wasnt. It was a sweater. But I dont think we ever got past that image of Michael Skakel in what appeared to be an ascot. He looked like a rich, snotty kid at Moment One, and thats who they found guilty.

Its true that many rushed to judgment. But the matter of his conviction was hardly so simple. Straw by straw, brick by brick, a state inspector named Frank Garr had been building a case against Michael Skakel since 1995, the year he learned Skakel had told private investigatorshired, ironically, by his own familythat hed lied to Greenwich detectives back in 1975. Instead of going to bed on the night Martha was killed, hed gone prowling about her yard, trying to peek in her window. Frank Garr already had his suspicions about Michael. But the new account changed everything. Now, Garr knew, Michael had put himself in the killers footsteps.

Michael had always existed on the fringe of that snapshot in time. It was his older brother Thomas, the last known person to see Martha alive, who had borne the brunt of police scrutiny. In the early nineties, the focus shifted intensely to Kenneth Littleton, the family tutor, who had moved into the volatile Skakel household on the day of Marthas murderredefining what it means to have a bad first day on the job. Littletons life began falling apart in 1976, during a wild summer of drinking, drugging, and petty crime on Nantucket, and failed polygraphs then put him in the bulls eye. It appears now that his lost summer was the first sign of a mental illness that plagues him to this day.

As Garr began to pick up Michael Skakels trail twenty years into the investigation, he made two startling discoveries: a series of damning statements Michael allegedly made in the late seventies while confined to a nightmarish reform school in Maine, and a 1997 book proposal of Michaels in which he unwittingly provided a motive for killing Martha. In the end Michael would hang, as it were, by his own words.

Not everyone agrees, however, that the State of Connecticut got the right man. Some who are well versed in the case still believe Thomas was the culprit, and others keep blaming Littletonthe one suspect I feel certain had nothing at all to do with Marthas death. There are still other theories and suspicions, too, tossing about on the wind. Members of the Skakel family point to a couple of Bronx boys who were supposedly in the Belle Haven neighborhood that night, planning to attack Martha. (I discuss this further in the epilogue.) In my view the story is a tall tale, but it did persuade one Connecticut Supreme Court justice that a new trial was in order, but, unfortunately for Skakel, his was a minority opinion.

In 2003 Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., published a vigorous defense of Skakel in The Atlantic Monthly titled A Miscarriage of Justice. Skakel helped Kennedy get sober in the early eighties, and the two spent much soul-baring time in each others company. I know Michael Skakel, my first cousin, as well as one person can know another, Kennedy wrote. But by the time of Skakels arrest, the two were estranged. The rift owed first to Skakels perceived meddling in a private Kennedy disgraceMichael Kennedys affair with his young babysitter, whose side Michael Skakel rightly championed. The rift deepened when Skakels tell-all proposal for a book called Dead Man Talking surfaced in the late nineties; in it, Skakel aired a full load of Kennedy dirty laundry. That Robert Kennedy would still go out on a limb for his turncoat cousin demonstrates his genuine faith in Skakels innocence.

But A Miscarriage of Justice is a miscarriage of journalism. Most readers of Kennedys well-turned, fact-packed sentences could never guess how far they had been led astray. The authors reckless treatment of Ken Littleton disturbed me particularly. If I didnt know the case intimately, I would come away believing that Littleton was inflamed and in an alcoholic stupor on the night of the murder; that he confessed to killing Martha multiple times; and that hes possibly a serial killer to boot. I shook my head in dismay: Littleton, a scapegoat once more.

Not long after Kennedys piece appeared, I picked up my phone to hear his halting, nasal voice on the line. He was still scouting around for pieces of the puzzle. I had to admire his tenacity on Skakels behalf, if not his sense of fair play. When he asked me what I thought of his article, I told him that I didnt think much of it, and our cool conversation went cold. Later, when I critiqued A Miscarriage of Justice in the

Next page