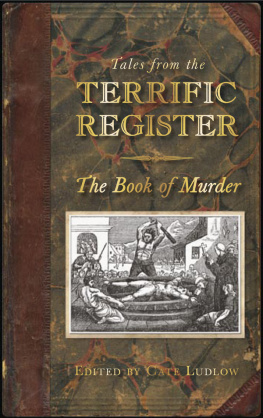

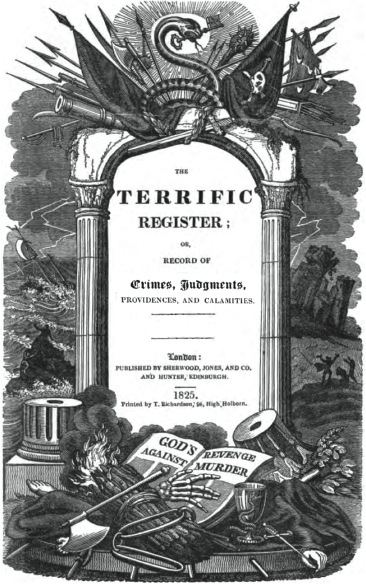

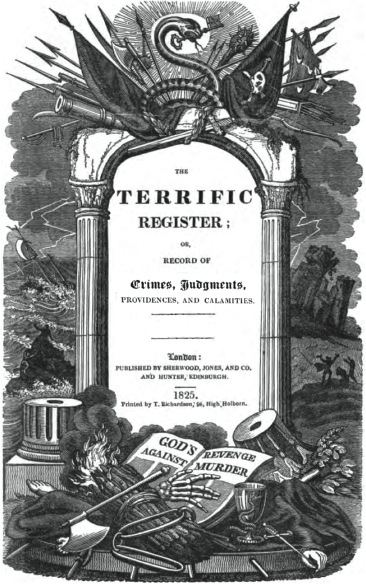

Tales from the

TERRIFIC

REGISTER

The Book of Murder

First published 1825

This edition first published 2009

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2014

All rights reserved

Cate Ludlow, 2009, 2014

The right of Cate Ludlow to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 6174 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

Tales from the

TERRIFIC

REGISTER

The Book of Murder

EDITED BY

CATE LUDLOW

Horrible Murder Of A Child By Starvation

The annals of crime scarcely furnish a more diabolical instance of cruelty than the one we are about to record; but the circumstances of the murder are eclipsed, in the point of hardened depravity, by the means taken to conceal it.

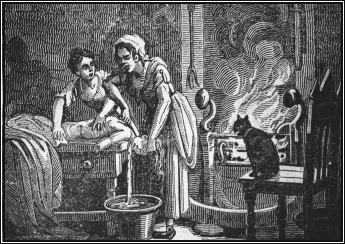

In July, 1762, Sarah Metyard and Sarah Morgan Metyard, mother and daughter, were placed at the bar of the Old Bailey for the murder of Ann Nayler, a girl, thirteen years of age, by shutting up and confining her, and starving her to death. There was also a second indictment for the murder of Mary Nayler, her sister, aged eight years. The unfortunate child (Ann) it appeared, had been apprenticed to the elder prisoner, and it was principally on the evidence of her own apprentices that she and her daughters were convicted. They deposed that about Michaelmas, 1758, Ann Nayler attempted to escape, she was used so ill; being frequently beaten with a thick walking-stick and a hearth-broom, and made to go without her victuals. The day she endeavoured to run away, a milkman who served the family stopped her, as she was running from the door, and brought her back to the prisoners. The daughter dragged her up stairs, and while the mother held her head, beat her cruelly with a broomstick. She was then tied up with a rope round her waist, and her hands fastened behind, so that she could neither sit nor lie, and in this position she remained for three days, without food. During this period she never spoke, but used to stand and groan. At the end of the three days, the witness observed that she did not move; she hung double; and when this was mentioned to the daughter, she said shed make her move. She ran up stairs, and struck her with a shoe, but there was no animation in her. The mother came up, laid the child across her lap, and sent one of the girls for some drops. The girls were ordered down stairs, and the unhappy victim was never afterwards seen by them. In the order to remove the suspicion of her death from the minds of the apprentices, by leading them to imagine she had made her escape, the old woman two days after this left the garret door open, and the street door ajar, and sent one of the girls up stairs to tell Nayler to come down to dinner. The girl returned with the intelligence of the door being open, and Nayler missing. The old woman made answer, She is run away. I suppose she ran away while we were at dinner. The girl replied, Then she has left her shoes behind her. O! returned the other, she would not stay for her shoes.

Richard Rooker deposed that he lived in the prisoners house about three months, which was long since the child had been missing. He observed the children were very ill used, and had very little food. When they had any, they were not allowed more than five minutes to eat it. The old womans disposition was so violent that he was obliged to remove; and out of compassion to the daughter, who was repeatedly beaten by her, he took her into his service. The mother, however, would not suffer her to remain in peace. She came almost every day, insulting the witness and the daughter. On one occasion he heard the cry of murder; and going into a little room, he found the girl in agonies, struggling with the old woman. She had driven her up into a corner, and had got a sharp-pointed knife in her hand, with which she was attempting to stab her. During the altercation he heard the daughter say to the mother: Mother, mother, remember the gully-hole. Some time after, he questioned the girl as to the meaning of those words, when with great reluctance she told him that the child and her sister had both been starved to death. That a few days after Ann Naylers death, the body was carried up into a garret, and locked up into a box, where it was kept upwards of two months till it became putrefied, and maggots came from her. The mother then took it out of this box, cut it into pieces, cut off the arms and legs, and burnt one of the hands in the fire, cursing her that the bones were so long consuming! Saying the fire told no tales. Then she tied the body and head in a brown cloth, and the other parts in another, being part of the bed-furniture. She carried them to Chick Lane gully-hole, and threw them in. Her mother told her that, as she was coming back, she saw one Mr Ineh, who kept a public house near Temple Bar, who cried out, what a stink there is! to which she replied, that he had it all to himself, for she smelt none. She called for some brandy and went away. In consequence of this confession, Rooker wrote a letter to the officers of the parish where he dwelt, acquainting them with the particulars.

Thomas Lovegrove, overseer of St Andrews, deposed that on the 12th of December, at near twelve at night the constable came to him with two watchmen, and told him there were parts of a human body lying at the gully-hole in Chick Lane. He went with them to the spot, and the smell of the body was so offensive, that the watchmen were unwilling to remove it. It was at length taken to the work-house; the parts were washed, and laid upon a board; a coroners inquest set upon it, and returned a verdict of wilful murder. In the meantime, in consequence of Rookers letter, the mother and daughter were apprehended.

Some other witnesses were examined, who corroborated the essential parts of the above evidence. The mother, when asked for her defence, told a lame story of the girls running away, and called one or two witnesses to prove that she used her apprentices well, and gave them sufficient food, but in this they failed. One of them said he had he had never been in her house at meal-times, and never saw the children have any. He described the place in which they worked to be a little slip room, two yards wide at the widest part, and tapering at the end.

The daughter denied all participation in the murder excepting the concealment; and threw all her odium on her mother. When the girl was dead, she said, I desired my mother to apply to the parish to have her buried. She said I was a fool, for if she did, every body would see the girl had been starved; and if the girls were asked, they could tell how long she went without victuals. I then asked her to get the other girls not to say how long she had been kept without food: but this, she replied, would be useless, as it would be discovered on opening the body. She told me if I would stay with her till she was out of danger, I should go to service. When I thought she was out of danger I begged to go to service, as she proposed. She said, no, I should not; I should stay with her while she was in the house. She said I might tell and be d----d; for if I did, she would swear I killed her, and that she secreted my crimes. The body was never buried. She wanted me one night to help her in dividing the body in pieces, and said I need not be afraid of her now she was dead, for she would not bite me. This was two or three months after the girl died. I told her, indeed I could not. I was then with her up in the room; I offered to go out; but she told me I must help her. I got out of the room; and she caught hold of my clothes. I cried. She said, what would the girls think, seeing me cry so? How could I be such a cruel brute as to leave her? I told her she had brought it on herself, and must get out of it how she could. After that, she told me she had done the limbs up in one bundle, and tied the body and the head up in another. She tried to take the head off, but could not. She brought them down stairs, and first took the limbs out, and carried them to the gully-hold in Chick-lane. She said she tried to fling them over the wall, but could not. Then she came and took the other bundle, which she said she carried to the same place, and found the other parts lying there. One night, after the children were gone to bed, she brought down the hand which had a stump finger, which she said she would make away with in the fire, because the fire concealed every thing. Here the elder prisoner interrupted her daughter, by saying it was all false; and that if she had burnt any part, she might as easily have burnt it all. To which the other replied, that she said she would destroy it all by fire, but it would make a smell, and alarm the neighbours. The daughter called a few witnesses to character; but both prisoners were found guilty. Death.

Next page