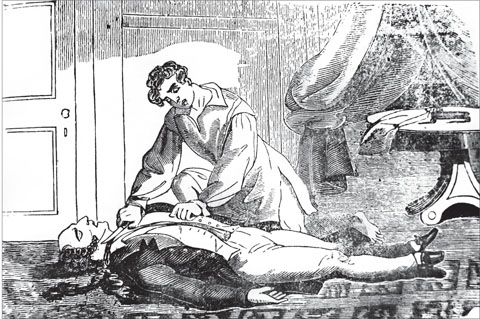

James Hall, who murdered his master in June, before carefully draining his blood into various pots and pans, and hiding his body. (See 18 June)

INTRODUCTION

The years between the accession of George I on 1 August 1714 Queen Anne having succumbed to gout and the death of George IV on 26 June 1830 was one of the most eventful centuries in British history. It was certainly one of the bloodiest: from the French Revolution to the Napoleonic Wars and the American Revolution, some of the key events which defined Britain occurred in this age. Many of the events need no introduction: the Battle of Waterloo, for example, or the Declaration of Independence.

This age was defined by four Georges: German-speaking George I (king from 1 August 1714 11 June 1727), whose reign started with a Jacobite rebellion and who was born on the day that the victim of another rebellion, Charles II, re-entered London in triumph; George II (king from 11 June 1727 25 October 1760), who promised his wife, on her deathbed, that he should not remarry No, I shall have mistresses!; George III (king from 25 October 1760 29 January 1820), the first George with English as his first language, whose reign saw the establishment of an independent United States and the battle against Napoleon twice and whose blindness, deafness and madness are legendary; and finally, George IV, the Prince Regent (who reigned as regent from 5 February 1811, and as king from 29 January 1820 26 June 1830). There are a few royal incidents in this book, including two of the most famous in the life of Queen Caroline, who unsuccessfully hammered on the door of what should have been her own Coronation (see 19 June).

The era began at the last dusk of the Golden Age of Piracy (and indeed, Mary Read of Bonny and Read fame was born in London) and was coloured a pleasing shade of crimson by the all-encompassing, notorious Bloody Code a system which meant that, by 1815, a total of 220 offences carried the death penalty. Hundreds of Londoners stepped into the shadow of the Triple Tree at Tyburn now the site of Marble Arch or on to the gallows set up at Newgates debtors entrance (the site of Londons hangings moved in 1783). Executions at Tyburn were marked by the roar of the crowd, the oaths of the men and women climbing into the cart to be hanged, and the swishing of missiles dead cats, sticks, dead dogs, stones, offal, dung flying thickly through the air as the cart creaked along the route from Newgate to Tyburn. A psalm was sung over the roar of the crowd, last speeches were made, cheers went up for a popular rogue and oaths and boos for unpopular ones, such as Mrs Brownrigg, whom thousands of people wished into Hell and then, as the feet of the prisoner left the wooden platform of the cart, the crowd would surge forward to fight for a souvenir, or for the body, which the surgeons needed and the family wanted to protect. After the Murder Act was passed in 1751, supplies became somewhat more plentiful, as the Act demanded that every murderer be dissected or hung in chains after death. This led to some colourful resurrections on the doctors table.

Other methods of execution in this volume include: hanging, drawing and quartering, where the offender was choked, ripped open and his internal organs pulled out and burned in front of his eyes (after the genitals, of course); beheading with an axe, as in the case of Derwentwater and Kilmarnock; burning, as in the horrible case of Catherine Hayes; and decapitation after death, as in the case of the Cato Street Conspirators. In several instances, a bleeding skull was held aloft to the cry of, This is the head of a traitor! Other corporal punishments included the pillory a death sentence in itself in many cases and the hot irons (burning on the hand for manslaughter), as well as whipping, which a London hangman once refused to perform until he got a pay rise.

It has not been possible to fit every grim event of the Georgian era into this book the subject could fill many volumes: one volume on high life and royal scandals; one on politics and war; another on the brothels, gentlemens clubs and sexual scandals of the day. We have chosen to concentrate, in this volume, mainly on crime in the capital and what crimes they were! From the cupboard murderer, John Williamson, to the death of the Marrs (and another set of Williamsons) in Londons East End a Georgian serial killing that has never been conclusively solved all manner of life and death is in this book. Almost all of the research has involved primary sources taken straight from the magazines and newspapers of the day, or from the trial records available at the magnificent Old Bailey Online.

We must thank the compilers of the phenomenal websites Capital Punishment UK (http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/) and georgianlondon.com, and also the people involved in the Old Bailey project: their exemplary research has made researching this book an absolute pleasure. We would also like to thank Neil R. Storey, who kindly provided some extremely rare images from his own collection for this volume. Graham and I both hope you enjoy reading it.

Graham Jackson & Cate Ludlow, 2011

JANUARY

Elizabeth Canning, who vanished on the evening of 1 January. Had a London gypsy really stolen her underwear and locked her in a hay loft?

1 JANUARY 1771 On this day, John Joseph Defoe (grandson of Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe) was hanged at Tyburn, along with John Clark. They had been convicted of the highway robbery of Mr and Mrs Fordyce, who were travelling in their carriage to London. There were three pistols in the coach at one time, said Mr Fordyce. They put a pistol to my head, and another to my wife; the third pistol was pointed to a gentleman sitting on the other side of the coach. The thieves took their watches and their cash. The criminals were later identified, apprehended Clark was cross-eyed, and hence very memorable and tried at the Old Bailey, where they were found guilty and sentenced to death.