I WOULD LIKE FIRST OF ALL to thank my wife, Eva, for listening to me while I have tried to establish the basic idea for this book. I needed someone to bounce my ideas off and Eva, unfortunately for her, was at hand: to discuss, assess and advise on the progression of my thoughts.

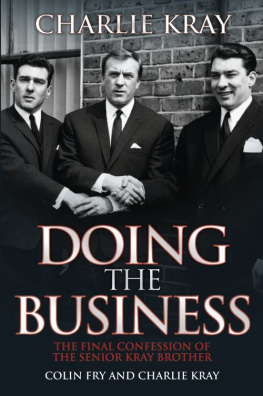

Later on I was ably assisted by Robert Smith, my previous publisher, who spent many a day with me finalizing the concept of the book. I will always be thankful for his involvement. This team effort was continued with John Blake at Blake Publishing, who encouraged me to update Doing the Business, thus involving previously researched material considered at the time to be too dangerous to include in the original book back in 1993.

A special thank you must go to Richard F. Young of the Hartley Library at Southampton University. Early on in my research, he gave me great assistance and put the university library facilities at my disposal. On a personal note, I would also like to thank Southampton University for my recent BA Hons degree, awarded through King Alfreds, Winchester.

Likewise, I will always be grateful to Charlie Kray (although I could have done without the threats), without whom this book would have been an impossible task. His efforts were relentless and his memory exceptional as he helped me to appreciate the style of business favoured by the twins, Ron and Reg Kray, his brothers.

And last, but not least, I would like to thank my good friend Charles Rosenblatt, without whom this book would never have been attempted. His guidance during the evaluation of my synopsis was invaluable, and I can still remember his opening words: Everyone has at least one good book in them. With 40 years in the motion-picture business, he should know what he is talking about.

C HARLIE K RAY IS DEAD - but he is not forgotten!

On 4 April, just into the start of the new millennium, Charlie Kray succumbed to the effects of a sudden heart-attack and quietly passed away at St Marys Hospital, only a stones throw away from Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight. He was, at the time, serving a 12-year sentence for his part in a 39 million cocaine smuggling plot. He died broke, homeless and alone.

The demise of Champagne Charlie made the front pages how Charlie would have loved to have seen the obituaries, the media hype, the gossip and the gas. And he would have been thinking all the time of the money he could have been making, selling his story loads of money, by the bucketful. He would have laughed all the way to the bank!

But the circumstances surrounding his death were all but cheerful, hopeful, colourful and there was no humour of any kind. The troubles surrounding Charlie Kray started in 1999 when he suffered his first stroke, causing him to have reduced circulation in his legs and feet. And he never overcame the effects of this, brought on as they undoubtedly were by the trial, the conviction, the appeal process and his imprisonment at Frankland Prison.

To his friends, Charlie had openly admitted his guilt in the cocaine smuggling operation but he was after the money, and in no way did he intend to go through with the deal. He was put under extreme pressure by the police officers involved to come through with the goods and being Charlie Kray, he knew exactly where he could lay his hands on 39 million worth of cocaine. That was always the problem it was his making and it was eventually his downfall. Everyone would confide in Charlie he knew where the bodies were buried, he knew who was doing what and to whom. He knew but he couldnt tell. That would be breaking his code and Charlie was an old-time criminal he believed in respect, in tradition, in honesty among thieves.

Certainly, Charlie felt that his current spell behind bars was a gross injustice it was a sting operation, set up by the Met to catch the last remaining Kray still at large. His feelings of outrage and his unmanageable frustrations were exacerbated by the fact that his first stretch in prison was a horrendous miscarriage of justice he had served seven years for helping to dispose of the body of Jack The Hat McVitie, when all the time he was safely tucked up in bed, with not a care in the world. He didnt know until the following day any of the events of the preceding evening, when his brother Reg Kray, urged on by twin brother Ron, stabbed McVitie to death. But the police wanted the Krays, all three of them, and there was no hope for Charlie, who was inextricably involved in the Firms activities. However, it may be well worth noting that Charlie Kray was never on the Board of any of the Kray companies, he was never in charge in any way, shape or form. But Charlie was always there to support the twins, to offer advice and to make a little something for himself, if he could, in the process.

His first time in prison had not been kind to him he remembered and remembered, and he regretted and regretted. But it did no good at all. However, he did promise himself that he would never be sent to prison again, never, not for anyone.

One way of trying to come to terms with his life, before and after prison, was to write, and I was privileged to be involved in the writing of this book. All the remembering, all the regretting it all served a new purpose, a way of redemption and a means of helping him to find his own way in life without the twins Ron and Reg Kray.

The second time around, first in Frankland and then in Parkhurst, was hard for Charlie Kray. He wasnt a youngster any more he was 70 years of age and a pensioner. He lost much of his hair after the first stroke and with the blood circulation problems he became a pitiful, frail and ghostly image of his former self. When he started complaining of chest pains, prison authorities at Parkhurst were quick to act they decided to send him to St Marys for investigations, medical not criminal. Their suspicions were well founded Charlie Kray was suffering from a heart-attack.

On the following day, Saturday 18 March, news reached Reg Kray in Wayland Prison, Norfolk. The message said simply, Charlie is dying. He immediately contacted the authorities at the prison and arrangements were hurriedly put together for him to visit Charlie on the Isle of Wight, probably for the last time. Reg hadnt seen Charlie for over five years not since his twin brothers funeral.

Reg Kray is no stranger to Parkhurst. He served at least 17 years, mainly in isolation, at this establishment he knows all the rules, all the regulations. He wasnt keen on going back there, and the thought of confronting Charlie, possibly on his death bed, was not what he had wanted.

At around 8.00am on the morning of Sunday, 19 March, Reg Kray, together with three trusted warders, left Wayland Prison in a white van, driving carefully and slowly through the giant main doors of the prison. The van had arrived earlier, at around 6.45am, but it had to be inspected and checked, even by a sniffer dog, before Reg could be safely put inside. They were taking no chances with their prize prisoner.

The van was quickly on to the M11, and then the M25 around London, to the west. At around 11.00am the warders were hungry so they pulled into Winchester Prison, a scheduled stop for lunch. The meal was the usual thing, something good for the warders, something not so good for the prisoners, but Reg couldnt eat much he kept on thinking of Charlie. He wanted to get there fast at any cost.

The white van, complete with its occupants, made the ferry at Porstmouth early in the afternoon and by mid-afternoon they had reached St. Marys Hospital and the dying Charlie. Reg had endured the entire trip handcuffed to two warders, except for a brief interlude when waiting for the ferry, where he was allowed to smoke a cigarette or two while one wrist was freed. On this first day he was allowed to see Charlie for around 45 minutes, still handcuffed to the two warders, one on each side plenty of time for a quick chat and a few words of encouragement. Charlie hugged his brother, nothing could dent the Kray spirit, but his legs were already beginning to turn black, and the feeling had gone. Reg was under no illusions it was all true. At 73 years of age, Charlie hadnt long to live.