THIS IS A CARLTON BOOK

Design copyright 2008 Carlton Books Limited

Text copyright 2001 Peter Gerrard, Joe Lee and Rita Smith

Illustrations copyright 2001 Peter Gerrard, Joe Lee and Rita Smith, unless otherwise stated

This edition published in 2008 by

Carlton Books Limited

20 Mortimer Street

London

W1T 3JW

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior written consent in any form of cover or binding other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition, being imposed upon the subsequent purchaser.

All rights reserved.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN 978-1-78011-053-0

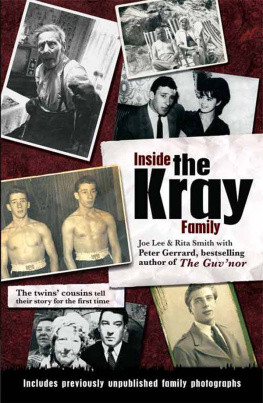

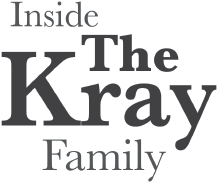

The twins cousins tell

their story for the first time

Joe Lee & Rita Smith

with Peter Gerrard, bestselling of the The Guvnor

Dedication

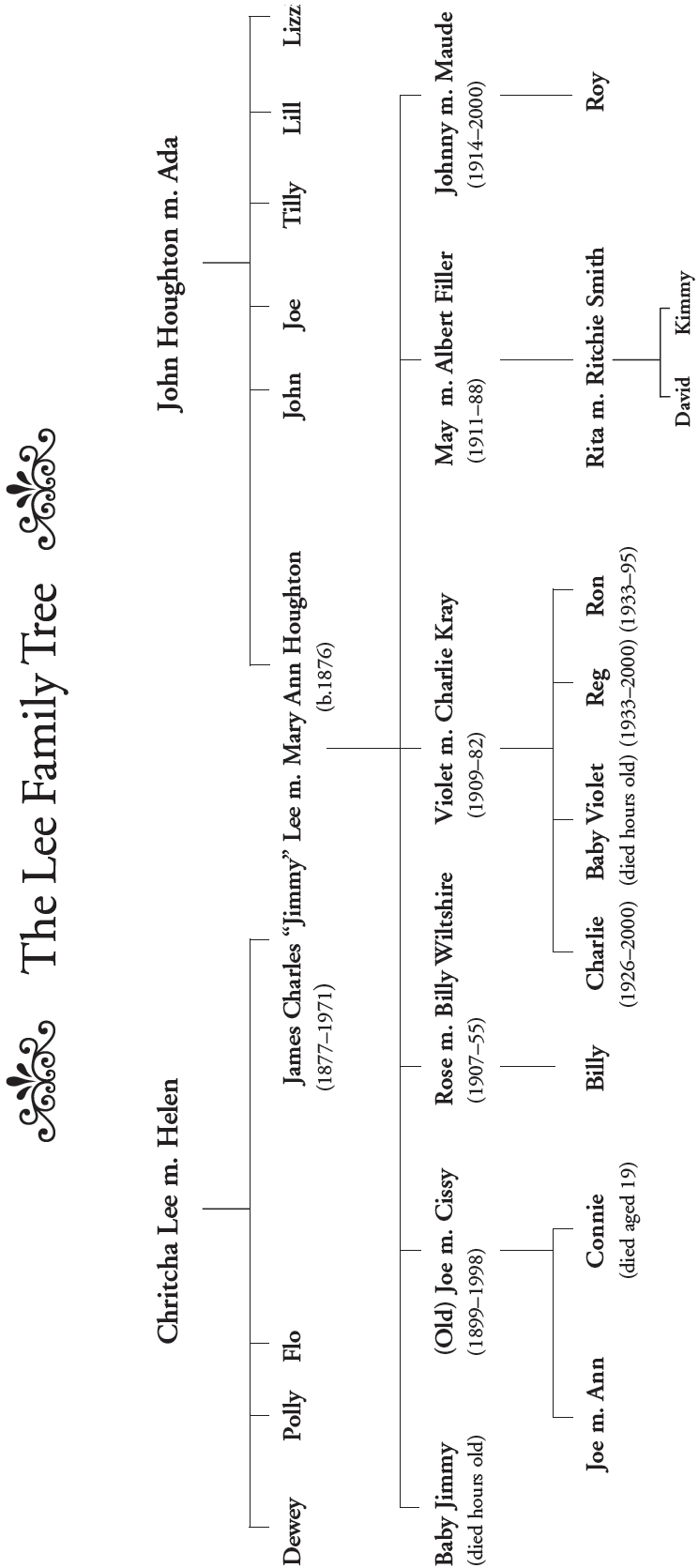

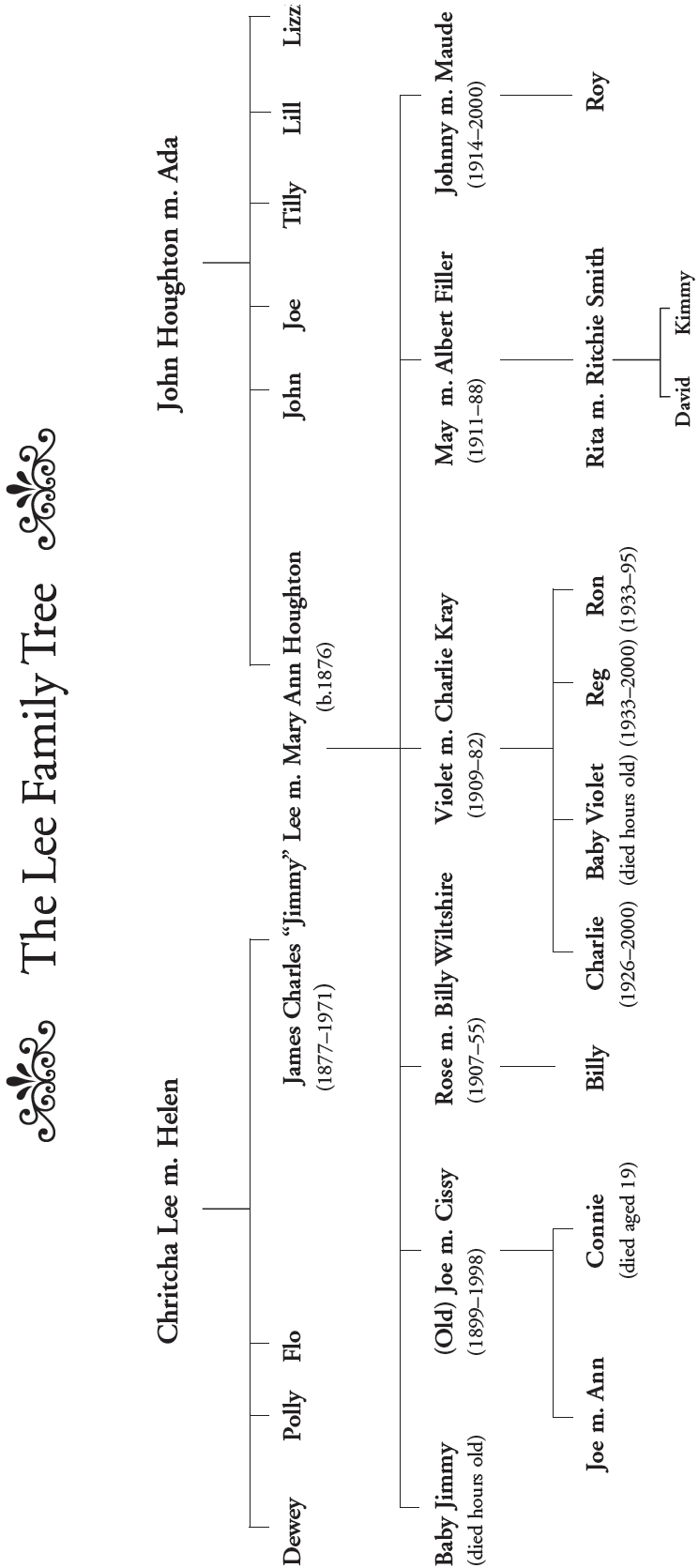

R ITA S MITH In memory of my mum and dad, May and Albert Filler and for my children, David and Kimmy.

J OE L EE To The Lee family who Ive been proud to be a part of and my wife Ann. She probably kept me on the straight and narrow.

P ETER G ERRARD To my wife Shirley whose honest criticism, editing skills and encouragement make my half of our partnership the easier option.

Introduction

Peter Gerrard

Ronnie Kray never tired of telling anyone who would listen that he was descended from a mixture of nationalities: Gypsy; Jew; German; Austrian; Irish; Dutch. No doubt he would have loved to add Sicilian to the list but this would have stretched an already overstretched truth. Reggie was more indifferent to the past but to Ronnie this colourful patchwork of ancestors set him apart, which was a state of affairs he strove for from an early age.

If he had had the inclination to study the past, he would have found that rather than set him and his family apart, these mixed-race origins were shared by most other East-Enders around him. For that part of London that lay to the east of the Tower had been first base for incoming communities since the 1700s.

Separating fact from romantic conjecture, it is family knowledge that Krays and Lees were in east London during the mid-nineteenth century. The great great grandparents on both sides seemingly arrived in the land of plenty around the late 1840s, which would fit into the history of what was happening in Europe and elsewhere around that time.

The London they disembarked into, from the decks of tall sailing ships, would barely change for at least another eighty years as far as social conditions for the working classes were concerned. Overcrowded streets seething with traders aside, the most powerful impression that would strike them would be the smell. As a boy fifty years ago I can remember days when the stink from the Thames at low tide was unbearable, and that was when the river was comparatively clean and I was some two miles away. A hundred and fifty years ago it was not only the river that polluted the air but the very streets. For at that time London had no system of underground drainage whatsoever and it would be another ten years before this was rectified. Until then Londoners continued to pour every conceivable type of waste into the open street-drains where it found its way into larger open channels before discharging into the Thames. Small wonder it was known as the Venice of drains. Many if not most of the stinking waterways that were turned into fetid drains were in earlier days rivers and streams, though people of the time might have been hard pressed to imagine them as anything other than the way they were. Though they have now disappeared inside brick culverts these medieval courses are still flowing under the feet of unknowing Londoners.

For those fortunate enough to have piped water in their homes or at least access to a standpipe shared by perhaps ten families, the advantage was tempered by the fact that the supply was only turned on for a couple of hours every other day. With no public services and city government not to be established until 1888 water was a commodity sold by a few private companies with no other thought than profit. For most, without this intermittent trickle, the alternative was to take all their liquid needs from those drains and small streams that carried the sewage. The only precaution taken against the filth and unimaginable debris that floated in the water was to fill a barrel one day and leave it overnight, by which time all the sediment would have sunk to the bottom leaving clean fresh water ready for use. Most must have been so immunized by this daily intake of microscopic disease that they were able to shrug off the worst effects of the contaminated water. But Londons other nickname,Cholera City, suggests that not everyone escaped so lightly.

The first thing our families would have to do, even before registering as aliens, would be to find some sort of accommodation. Now, when you allow that in Whitechapel, as an example, on each acre there lived in excess of 270 people, while in Hampstead one person per acre was the norm, they were going to face a problem. Their choice would be between a room in a common lodging house or a room in one of the hundreds of inadequate houses situated in courts, closes and blind alleyways.

At the turn of the nineteenth century the population of London was around the one million mark. Only fifty years later it touched two and a half million, with the highest proportion of inhabitants living in the east. Overcrowding was made even worse when thousands of residential properties within the city were torn down to make way for commercial outlets like offices and warehouses. To meet demand jerry-building outside the limits became rife, as London was cut up by new road and railway tracks.

Businessmen and artisans left their neat houses and fled to the suburbs. These inner-city properties were then divided and subdivided to the extent that, instead of sheltering one family, they became the single-roomed homes of ten families. But demand still outstripped supply so, without any planning or quality controls being in place, below-standard housing was thrown up on every available space, turning many areas into little more than shanty towns. Houses that were once airy and well ventilated became hemmed in and overshadowed by new buildings that began to deteriorate as soon as the last brick was laid.

Such was the value of every square foot, that the single entrance to perhaps twelve houses would be a narrow alley leading to a dark and sunless centre court that might never feel a breath of moving air. This area of twelve metres by nine would have three or four privies for the use of some sixty families, or between two and three hundred individuals.

Through no fault of the tenants these rookeries, as they were known, were manufactured slums from day one, and as such were mirrored throughout east London. A room for your family in such a place would set you back 8d. per night. A basement cellar, though it was illegal to let them out, could be had for 4d. However, since they lay six or seven feet below overflowing drains, the streets might have been seen as a preferable option. The fact that there were laws against letting out cellars shows that the authorities at least tried to keep standards up. Overcrowding too was illegal, and constables would regularly check out lodging houses to make sure the law was upheld. But there were many ways, not least a shilling for the peeler every now and then to look the other way, of avoiding the law, which most must have done because little changed for over a hundred years.

Next page