W orking South African journalists dont write books. We chase tons of stories every day, break them, drink beer and watch how the caf attendant wraps fish and chips in our precious work of yesterday. Tomorrow we wake up and do the same thing. Sitting in courtroom 4B of the South Gauteng High Court for over fifty days, listening to the gripping evidence being stacked up against the former Interpol president and South Africas police chief Jackie Selebi, I realised this wasnt just another story in which fish and chips should be wrapped.

Selebi was the most prominent civil servant facing corruption charges post-1994. He was a powerful member of the governing African National Congress and the stakes at play were huge. The investigation and eventual prosecution against him claimed the careers and reputations of mighty people. It fertilised the soil for the most efficient law enforcement agency in South Africas history the Scorpions to be shut down and exposed police corruption at the highest levels. The Selebi trial also exposed the ugly face of organised crime and showed how quickly and relatively easily its tentacles were able to reach into the office of the one man supposed to uphold law and order in the land.

Luckily, a number of special and courageous people agreed with me that this story needed to be recorded in a more lasting form than newsprint.

FOREWORD by Ferial Haffajee

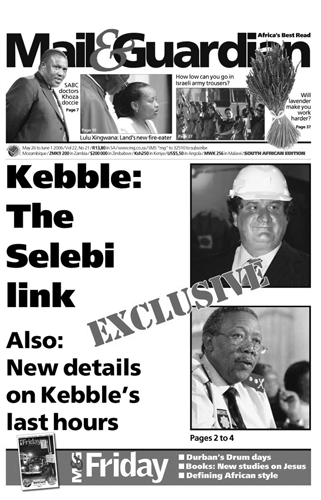

In May 2006, which feels like a lifetime away now, my colleagues at the Mail & Guardian came to me with a story, the basis of which was that the national police commissioner Jackie Selebi was on the take.

The Mail & Guardian s crack team of Stefaans Brmmer, Sam Sole and Nic Dawes broke the story and invited a storm upon our heads. The cops formed a thick blue line around Selebi, dismissing the story and the newspaper. Political pressure was intense and dirty tricks the order of the day, as Brmmer and Sole faced efforts to plant drugs on them and monitor their mobile phones. Later there was a raid on our offices and late-night attempts to gag the story.

Not Jackie, I remember thinking when they first told me of the story. The same incredulity peppered later conversations with my friend and fellow editor Mondli Makhanya when the Sunday Times followed our work. Not Jackie.

In my simplistic division of politicians, he was a good guy. He was not a Joe Modise, the former defence minister who was known to be corrupt and corruptible. Or a member of the Alex Mafia, the second generation of activists from Alexandra township in Gauteng, who treated the provincial fiscus as their personal piggy bank. Or even a Jacob Zuma, who at the time was at the centre of the arms deal scandal and who had been ousted for allegedly getting his bagman Schabir Shaik to ask for a half-a-million-rand allowance from an arms company.

As the investigation unfolded, we found that Selebi was at the centre of a Scorpions investigation christened, ironically, Operation Bad Guys. It shook my trust and political moorings as someone who believed intrinsically in the African National Congress as a largely moral force, which took care in its choice of cadres to lead the party. And it began a process of rapid political maturing in our country where we saw, graphically, through the investigation, prosecution and eventual conviction of Selebi, that power does corrupt. Sadly, corrosively, quickly, power does corrupt.

Jackie Selebis life story was one of those that taught us as young people the art of the possible. A schoolteacher, he was targeted by the system and had to leave the country. In exile his life was one of service in the achievement of freedom. He ended his life in exile at the United Nations in Geneva, where he built a reputation as a negotiator and lobbyist for anti-landmine and small arms protocols.

When he came back home, it was as a hero and a natural leader. As the first post-apartheid director-general of foreign affairs, he had his work cut out for him. How to take the isolated and shamed pariah state and capitalise on the global goodwill to build a geopolitical strategy that would deliver desperately needed investment and influence for South Africa? It was not an easy task but he acquitted himself well, and soon his friend and president Thabo Mbeki asked him to become national police commissioner.

With crime out of hand an unexpected and sour consequence of freedom Selebi was widely welcomed in our misguided belief that political activists made good crime fighters. Selebi soon revealed his arrogance when he called a young constable a chimpanzee because she was not reverential to him on a visit to a police station. It was an arrogance that would contain the seeds of his destruction. Selebi believed himself to be infallible, but the easy way in which he was lured by lucre speaks instead of a man who has not mastered the ways of the world even though he was a globetrotter.

Convicted drug dealer Glenn Agliotti courted Selebi and found his Achilles heel, a love of bling. While in the main Selebis court case has often been dry, it has been narrative of bling: the Fubu kit Agliotti sponsored for Selebis boys, tens of thousands in cash parcels and even expensive handcrafted leather shoes bought for Mbeki (Agliotti said he bought them; Selebi said he did).

As an aide to Selebi told me when he was convicted, none of this bling is affordable on a commissioners salary and so, somewhere in his conscience the commissioner justified these as gifts from a friend, finish and klaar. Thus was traded a reputation measurable in gold for a few pieces of silver. In essence, Selebi became a bellboy for Agliotti, available for dinners with others in the shady businessman network of cronies, on the other end of a phone line when there was trouble like Brett Kebbles gruesome death on the side of a Joburg road.

He dropped us, the nation, and all our trust in him for a cappuccino in Sandton City where he helped his friend Glenn out of several sticky situations.

When the charges were laid, Selebi was suspended and his friends quickly evaporated like the foam over a rapidly cooling cappuccino. His political support thinned to nothing by the day of his sentencing, when only his friends, family and his loyal wife, Anne, attended.

Alone, drained, grey, Selebi cut a pathetic figure. Abandoned, broke and bitter. Selebis is a cautionary tale, his story played out for national attention by ever-vigilant cameras.

My great and abiding fear is that we, or at least those who lead us, have learnt nothing, and that our criminal justice system is not sturdy enough to prosecute corruption in thorough and committed ways. Corruption is entrenched, from the metro cops who let you off for R20, to the mining officials who give up concessions to cronies in dubious circumstances, to the numerous shady tenders ticked as OK in provinces and municipalities everywhere. Corruption curdles hopes and dreams; it keeps wealth and prosperity circling within connected elites so that it never percolates downward. It destroys leaders and it harms trust.

All these trends are contained in this book written by the countrys most talented young investigative journalist. I hope it becomes one of those books that people talk about and learn from. It must teach us as ordinary citizens to say that corruption is not acceptable, whether small or grand.

Ferial Haffajee

Johannesburg

Haffajee was editor of the Mail & Guardian from February 2004 until her appointment as editor-in-chief of City Press in March 2009.

KEY CHARACTERS

Agliotti, Glenn: Convicted drug trafficker, and Jackie Selebis corruptor and (former) friend.