For my wife and family, to whom I owe everything

Contents

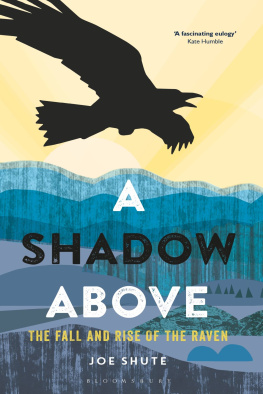

If you place your hand on the top of your shoulder and press your fingers into the muscle where the clavicle meets the scapula, you will find it: the coracoid process, a small curved piece of bone that holds the joint together and takes its name from the ancient Greek for the raven beak.

Or cast your eyes up to the night sky. The Corvus constellation sits just to the right of Virgo. The brightest of its stars, Gienah, which forms the shape of the ravens wing, is 165 light years from earth.

It is after work, and I am on my way home through the Peak District after three long days away, but the evening is still too early for the stars to show through the faltering light. I am parked by the side of the road, watching a raven that I had noticed foraging among the cotton grass on the roadside verge as I approached. I am not far from my house and know this bird: a haggard, fully-grown adult that I often spot on my way across the moors and like to think has lived here long before me.

As soon as my foot depresses the brake pedal, the raven takes flight with a languid ease, wings creaking into action as if attached to invisible pulleys. As it flies away from me, it pursues what has become a now familiar flight line, skirting the lower branches of a row of old oaks and parallel to a drystone wall bordering a small wooded enclosure. This particular raven tends to prefer to fly close to the capstones, the tips of its primaries almost brushing the curved tops as delicately as a quill dipped in an inkpot.

On the car radio they are talking about Manchester, from where I have just driven over Snake Pass, and the man who walked into a concert venue and detonated a shrapnel bomb in his rucksack, killing 22 people, mostly women and children, injuring 250 others and tearing himself in half.

My journalist colleagues and I had been tasked with piecing together and reporting on the horrors of his crime. I had driven between the bombsite and the vigils and homes of grieving friends and relatives. I had written about flowers and tributes and pink balloons released in memory of victims as young as eight. I had been called a vulture in one pub and been bought a drink in another. As Ive been driving home, those images have flickered in my thoughts like a showreel.

The raven comes to rest on a gatepost and sits looking back at me. I rub my tired right shoulder, massaging my fingers deep into the joint around the raven bone where my rucksack had chafed during the days on the road. The last rays of the sun pick out the shimmering, oily, midnight-blue in its plumage. I turn off the radio and wind down the drivers window, hoping to hear the bird call out in the twilight, but it maintains a silent solemnity.

I know this ravens territory, but not where it roosts, nor even whether it has a mate. After we consider each other for a while longer its long, steel-ringed talons skitter off the stones and its wings judder upwards taking it over the trees and out of sight. I contemplate the empty silence of the moor then start the engine to drive back home.

I feel as I always do when I have been watching a raven, a curious sense of realignment. I see in this bird of blood an emblem of my own age: a symbol of its darkness and yet still somehow one of hope; of the rise and fall of empires and the continuum of life; of the wildness we have lost and that which remains within us.

I was born in 1984, making me the flag-bearer of a strange generation. Raised in a comfortable home to a loving family, secure in the knowledge that, as the songs politicians played during the election campaign told us: things can only get better. And then, just as I had left university and started my first proper job in journalism on a local paper, along came the financial crash of 2007; and with it the collapse of all the misplaced entitlement of my youth. Since then, everything has changed. Things were getting more dangerous and unstable; we would never again have it so good. Rather than better, it was going to get far worse.

I could not say exactly when I started noticing the birds around me, but it was an interest that sharpened during this tumultuous time. As the certainties of one world started to dissolve, I began to delve into another that I had previously known little about. I suppose it was a release, at first, but I soon discovered a soothing surety in these ancient rhythms of migration and breeding; of fledge and moult. Learning more about birds helped me to become less fearful of my own world, even as it became an increasingly savage place to exist in. To be precise, I stopped seeing it simply as my world.

Ravens have always stood out for me. The sheer bulk of a bird that weighs in at 1.3kg (2.8lb) and possesses a wingspan of 1.5m (5ft) means you cant fail to be impressed. But aside from this statuesque presence that manages to encapsulate both eagle and vulture, there is an inner life to the raven that fascinates me.

For as long as humans have been on this earth we have attempted to explain ourselves through this soulful bird, drawn our maps upon it celestial and otherwise sought meaning and developed a specific and enduring culture through its twisted shapes and appetites. The raven has been our companion through the ages, and in Britain at the heart of its history. The bird with which we share flesh and bone is a bellwether for the fortunes of our nation; a harbinger of change and blurry black punctuation mark denoting the fall and rise of the epochs that have shaped us.

Ravens are coming back to live among us, returning to both the countryside and human settlements after centuries of exile. The more I watch and learn about these birds the more I want to discover the places and stories associated with them. I want to climb the ancient crags where they have nested for centuries, hear the muscle memory of their wingbeats overhead and fill my ears with their mysterious conversations. I want to visit the raven in the furthest extremities of these islands and also where they had once been feared excised for eternity and are now hiding in plain sight. I want to join the dots, draw my own maps and understand where and why they carve up territories for themselves and feel the bird driving back towards me. I find a deep thrill in the thought and sight of ravens returning. I seek through them a profound, feral meaning missing in modern life.

We have long attributed ravens with the ability to see further into the future than ourselves. In Roman literature and the stories of Ancient Britons the raven was often depicted as a prophet. A few months after the Manchester bombing, in the summer of 2017, a report was published by a group of Swedish researchers who had been studying five captive ravens at Lund University. Through presenting them with various challenges and rewards and monitoring the response of the individual birds to how they hoarded and bartered with food, the research team managed to prove ravens are indeed capable of thinking about the future. For the first time this study confirmed in the raven the power of foresight, an ability previously only documented by scientists in great apes and humans. Now this bird of augury is back among us, I wonder what it sees for our own dark times.

On Dungeness beach, a storm rolls in. The shingle boils with each washing-machine wave. Late afternoon turns to twilight, and blacker still.