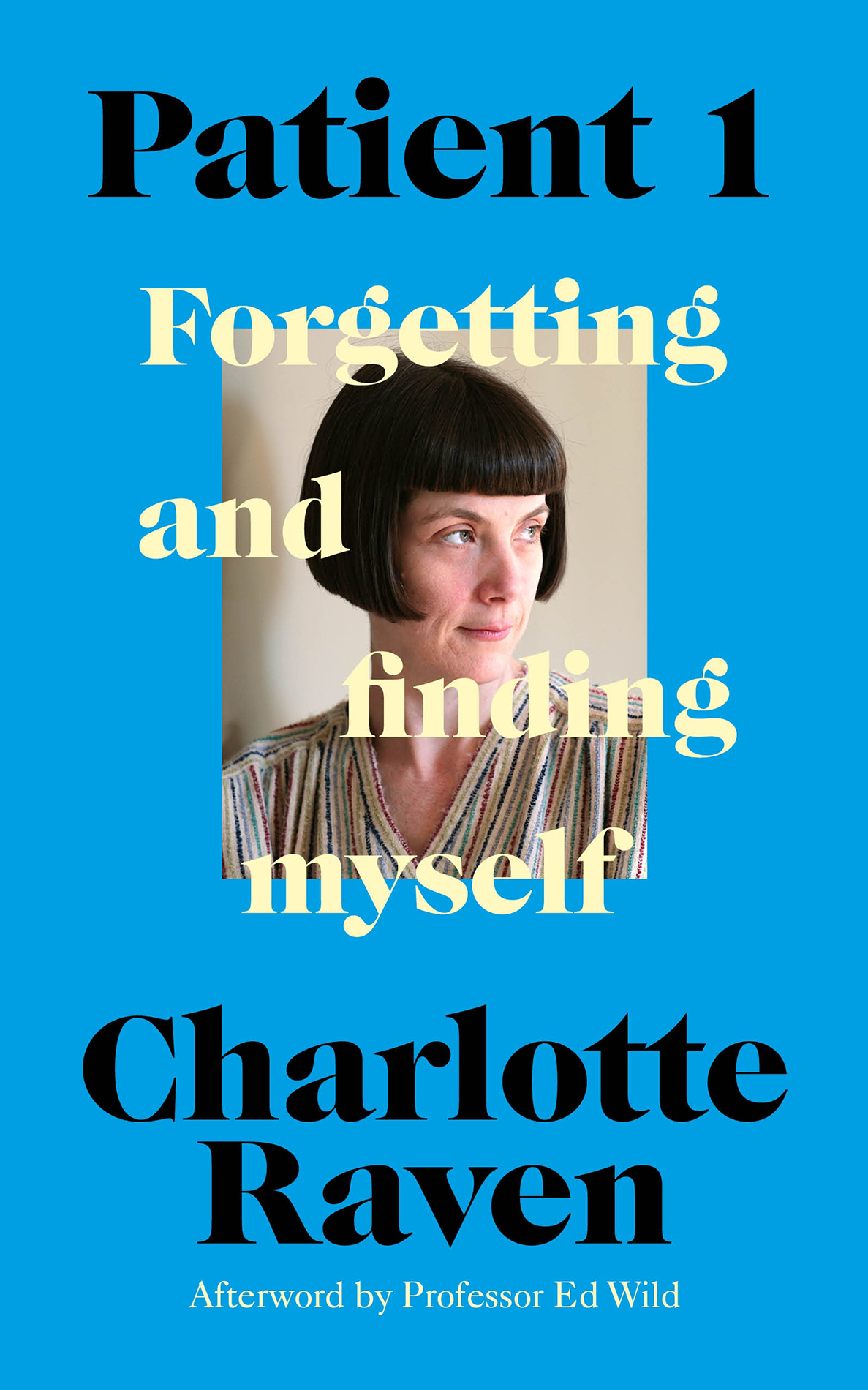

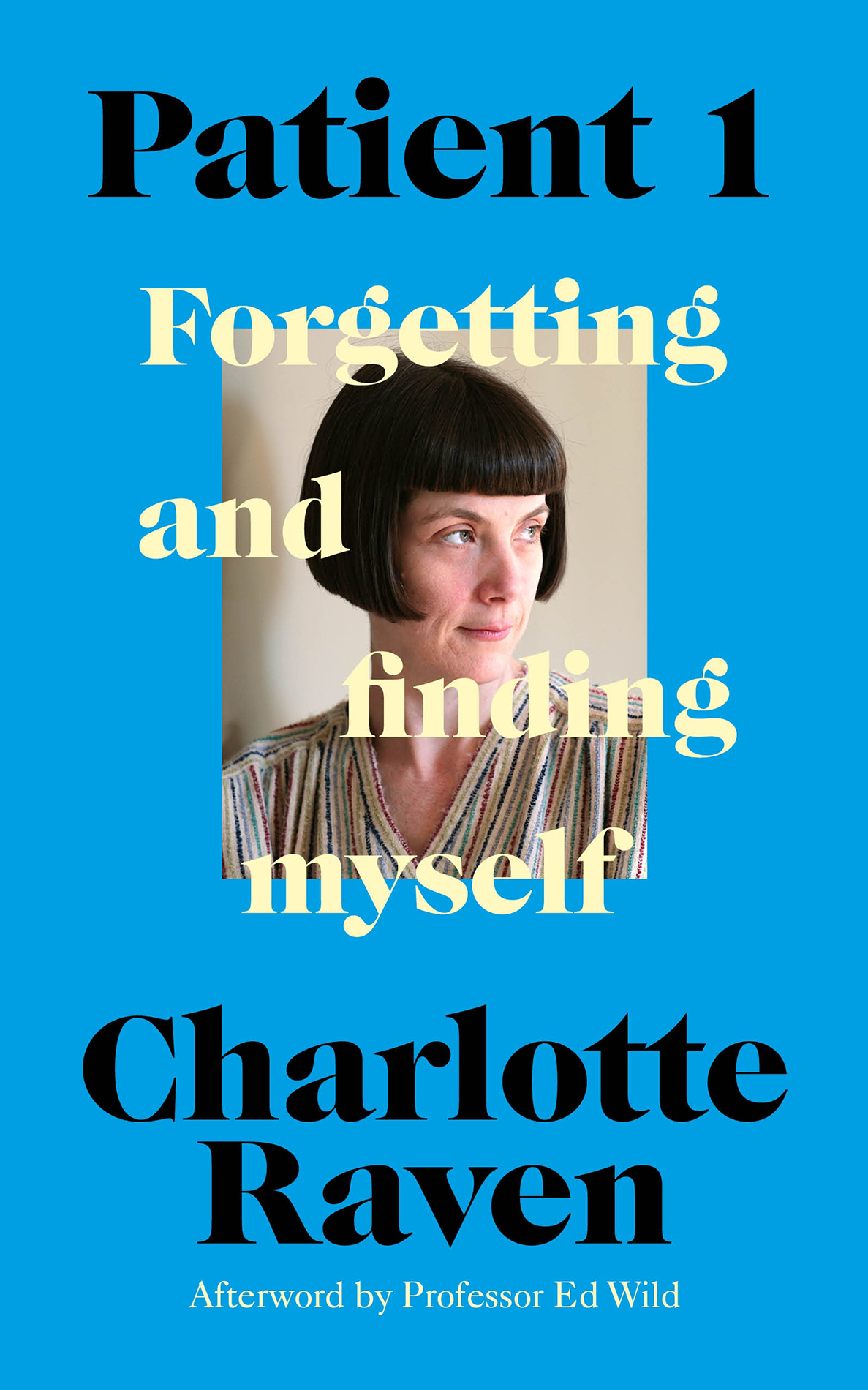

Charlotte Raven

PATIENT 1

Forgetting and Finding Myself

with Daniel Raven

with an Afterword

by Professor Ed Wild

Contents

About the Author

Charlotte Raven was a journalist in the 1990s and her columns and articles have appeared frequently in the Guardian and New Statesman. She was a contributor to the Modern Review, and editor of the relaunched version in 1997. She lives in London.

Professor Edward Wild is Professor of Neurology at University College London, a Consultant Neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in Londons Queen Square, and Associate Director of UCL Huntingtons Disease Centre.

To Anna and John

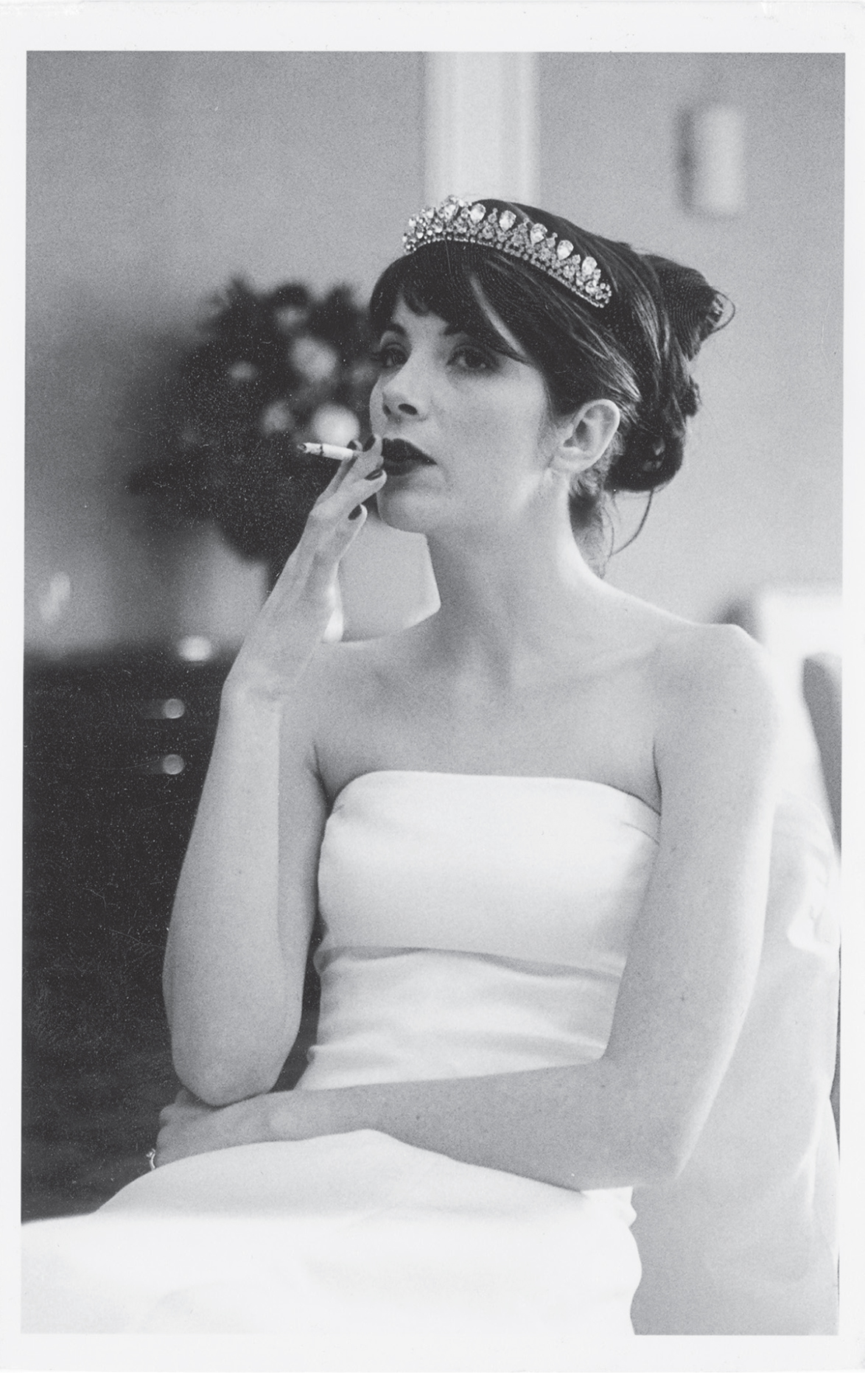

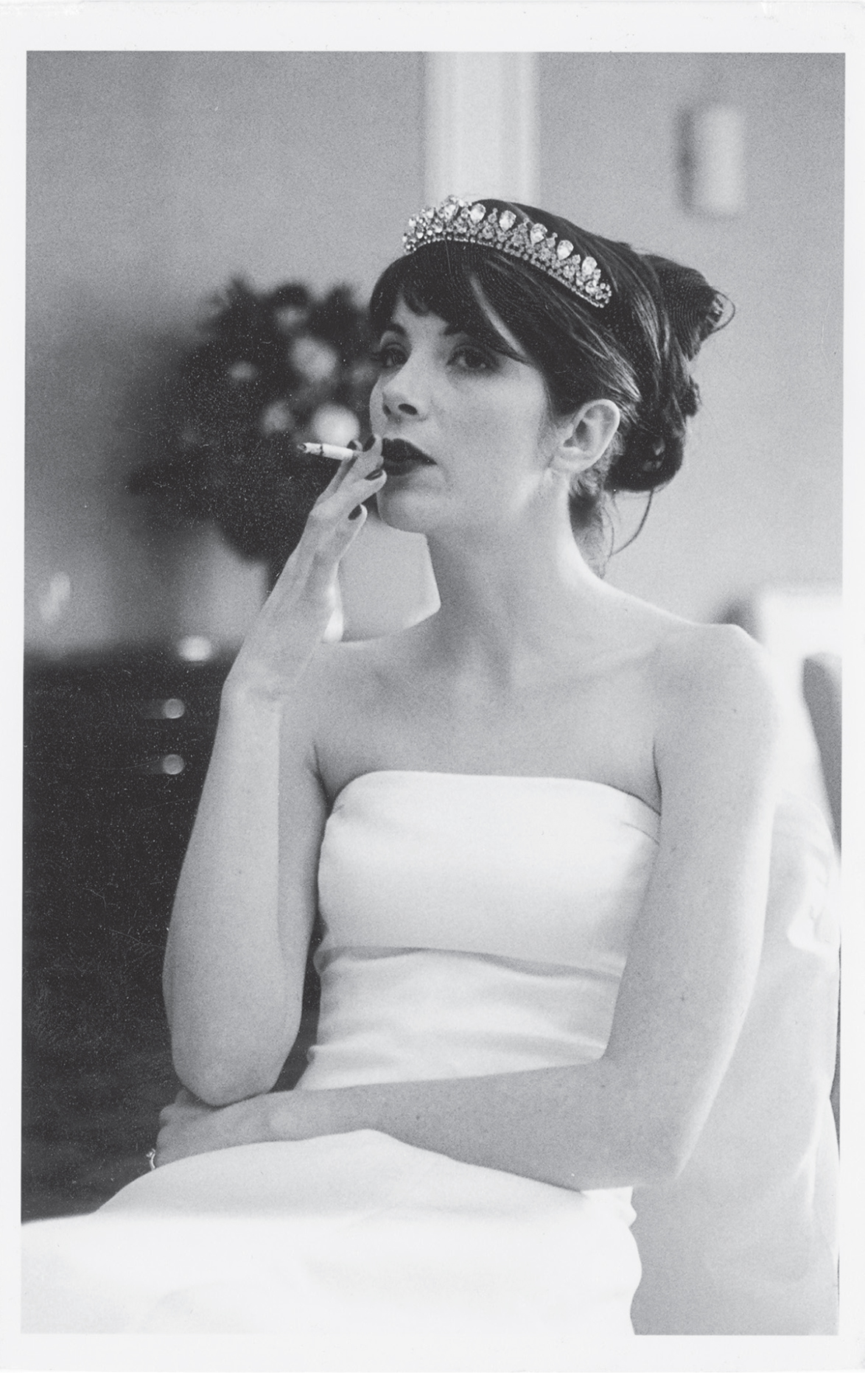

The smoking bride

Introduction

This book started life as an autobiographical blog about living with Huntingtons disease, a degenerative neurological condition that causes cognitive impairments, short- and long-term memory loss, changes in personality and a movement disorder called chorea. It is rare only 6,000 people in the UK have it so talking to medical professionals about it can be difficult, as theyve often never heard of it.

I started writing the blog in 2017 as an awareness-raising exercise, and was pleased when people from the HD community who had never reached out to anyone before got in touch and trusted me with their stories. I sent the link to the Huntingtons Disease Association, who asked if Id mind them sharing it with doctors and specialist care agencies, and I got lots of positive feedback when they did. Some of them said they could tell I was a professional writer.

This was only half true, though. I had indeed been a successful newspaper columnist in the 90s and often found myself wishing Id never given it up, but my history with longer form works was not a happy one. Conversations with my agent towards the tail end of my time as a columnist resulted in a book idea that seemed ambitious but achievable: a feminist conduct book about false consciousness addressed to an imaginary teenager. It was to be called Advice to a Young Girl on Avoiding the Illusions of her Sex a title I really liked and we found a publisher for it surprisingly quickly. I wanted to write a feminist classic that would be remembered and talked about for years after my death so no pressure, then.

The publishers were patient and I met the editor every few months to check in with him. I kept saying Id nearly finished but in fact I was just rewriting the first chapter over and over again. It took me ten years to realise that it wasnt working, by which time it had changed from a feminist advice book to a self-lacerating attack on my own narcissism. I shredded the 100-page manuscript and threw it in the bin, then deleted it from my computer so there would be no way back to it.

My children were shocked when I destroyed the book of doom in front of them but it felt good to me. When I eventually returned to my desk it was with a different perspective on writing, and more realistic expectations about what would be possible given my cognitive impairments and other difficulties. I felt like my story was backing up in my mind and I needed to find a form quickly; with HD attacking my memory, this really was the last chance saloon. A writer friend suggested I try writing a blog about the illness and its effects on the people around me, with some personal history woven in.

I called the blog Forgetting Myself, to reflect the fact that my identity was as imperilled as my cognitive processes. My carer helped me set it up and the friend whod suggested it edited it, so it looked quite polished. I updated it every couple of weeks and felt more emboldened with every post.

I worried what my husband Tom would think about the way I was portraying him, as our marriage was in the process of breaking down and I was chronicling that as well as the intrusions of my illness. It was a difficult balancing act and I may not always have succeeded, as my ambivalence led to inconsistencies: I deified him one minute and deplored him the next, when neither view was entirely justified. Mostly, though, I realised that the evidence Id amassed to indict him was outweighed by the case against me, and couldnt help feeling guilty about the way Id behaved towards him before I got ill.

HD is an interesting illness so I was never short of material, and at least I didnt have any competitors I was glad to be writing about a rare illness rather than, say, food or cats. But I soon started to feel like the posts were floating up into a cloud and never really landing anywhere, so in a cynical bid to give the public what they wanted I wrote about my deranged cat Archie, the Staffy of cats, who regularly attacked my carers and sometimes drew blood. I got more comments than Id ever had for the posts about my own derangement.

When Tom finally saw the blog, he called me out for invading our childrens privacy. But he was supportive of me and saw its potential to evolve into a book as I was secretly starting to hope it would.

Although it had never exactly been what youd call enjoyable, writing about my situation and trying to put the jigsaw-puzzle pieces of my life together on the page had felt therapeutic and even necessary. I wanted to extend this approach and bring in more stuff about my past while I could still remember it, but the blog clearly wasnt the right place for that. I wanted to write a book, but only if I could avoid the conventions of the standard misery memoir. I had many examples of this genre on my shelves but they were just for hate-reading I wasnt a fan. The authors all bragged about the journeys theyd been on but never really seemed to learn anything about themselves, and often ended up with bigger egos than when theyd started. For all their claims of searing honesty, they lacked self-awareness. If I didnt want to write something like that Id need an angle on HD that felt fresh and true to my experience. The illness had challenged me and precipitated an existential crisis that I wanted to explore without constantly moaning about my symptoms.

I had become friends with Dr Ed Wild, a warm and approachable HD specialist whod been there for me when the disease first sent my life spinning out of control, offering wise counsel on everything from barbiturates to my failing marriage. It occurred to me that if we worked on a book together, his medical account of the illness could complement my personal one. Ed said he was up for it and I was thrilled to have him on board; a joint enterprise felt much less daunting than a solo project.

We decided that the best way for me to approach my chapters would be to mix my recollections with updates on whatever was happening in my life at the time of writing, so that the end result would feel like a cross between an autobiography and a blog. It would be organised as a series of themed chapters, so the autobiographical elements wouldnt always be in chronological order, but the updates would.

This part of the plan rather alarmed me at first, as grouping my many and varied tribulations under neatly divided subject headings sounded like a much more challenging task than simply telling my story from A to Z, but then I realised that it made perfect sense: I had experienced HD as a dramatic, non-linear series of assaults, so any confusion in the books chronology would mirror mine.

Next page

The smoking bride

The smoking bride