For B

Contents

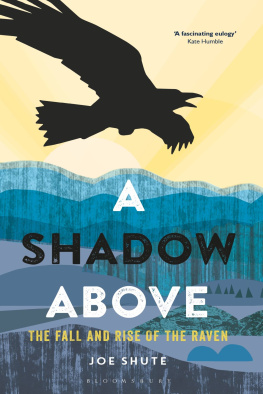

My thanks to all those who helped me weather various squalls. Grahame Madge at the Met Office, Paul Stancliffe at the British Trust for Ornithology, Kate Lewthwaite and others at the Woodland Trust, Tim Sparks, Nigel Hand, Alistair McLean at Museums Sheffield, Sue France and Jon Bradley at Green Estate, Ollie Douglas at the English Museum of Rural Life, Kieron Atkinson at Renishaw Hall, Rob Adams at the Spurn Bird Observatory, Kevin Walker and Louise Marsh at the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Viv and Nigel Smith at Claude Smith Ltd, Al Dix, Anne Storm and Norman Ackroyd.

My thanks also to all the readers of my Weather Watch column who, as well as being quick to correct my mistakes, have sent me so many entertaining and moving letters over the years. They make writing a privilege.

Once again my ace Bloomsbury editor Alice Ward has been invaluable in helping steer me through the fog. I am grateful to my copy editor Mari Roberts for her thoughtful suggestions and Jim Martin for taking a punt on me many seasons ago. Thank you also to my agent, Antony Harwood, and Jon Day for advice on early drafts of the book.

I am also indebted to my Telegraph editors, especially Vicki Harper, Jessamy Calkin and Jane Bruton for all their support.

Finally, thanks to my friends and family for their kindness and always keeping my outlook bright. To my mum, for her sharp eye for grammatical errors and being a sounding board for so much else. And most of all to my wife, Liz, for trusting me to tell our story in the hope it might help others.

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee

Shakespeare, Sonnet XVIII

The seasons are against us.

Professor Chris Whitty, Chief Medical Officer for England, 21 September 2020

It takes three weeks for spring to travel up the country, moving north-east at a rate of about 2mph. As I drove along the A1 in the early days of the first spring of a new decade, I wondered at which point I had passed it by. There was nothing else to overtake but the rising sap, roadside blossom and unfurling leaves. The Great North Road was so deserted I could drift across the white motorway lines.

Buzzards starved of roadkill perched on the treetops staring blankly over the empty asphalt. Some deer had ventured out of a patch of trees to graze the grass verges, nitrogen-enriched from the exhaust pipes of the tens of thousands of vehicles that on any usual day would be passing by. Insects spattered against the windscreen with a ferocity I had not seen since childhood, smearing a blood mosaic across the glass.

The road signs blinked STAY AT HOME . Police patrols were randomly stopping the few cars they could spot. But in my pocket was a piece of paper granting me special access to this spectral road. In the early days of the 2020 lockdown, brought in to contain the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic, I had suddenly gone from being a journalist to a key worker. And my newspaper had tasked me with travelling the length and breadth of the country, from north to south and coast to coast, to discover how communities were responding to the deadly new virus in our midst.

Over the course of that week on the road, my photographer colleague and I stopped at motorway service stations populated solely by the animated screens of Costa Coffee self-service machines. We passed Stonehenge, where the empty car park normally filled with coaches reminded me of a go-kart track. At night we stayed in any hotel we could find that had remained specially open for key workers.

One dilapidated seafront guesthouse near Eastbourne we shared with doctors working on the Covid wards, who didnt want to go home for fear of spreading the virus. As we passed one another on corridors that smelt of hand-sanitiser and bleach, we each shrank into our side of the wall, doing our best to crease our masked features into a recognisable smile.

Another hotel, an imposing Victorian building with sweeping views across Morecambe Bay, reminded me of the Overlook in The Shining . We were the only two guests staying among hundreds of empty rooms spread over two wings. The cavernous dining room was perfectly laid for a breakfast that never happened. We took our meals as instructed, alone in our rooms, watching the news for updates of the daily death toll and of the condition of the Prime Minister, who was in intensive care after contracting the virus.

Do you know what the people we met wanted to speak most about that week, as life as we knew it transformed before our eyes? The weather. That lockdown spring was, paradoxically, the brightest on record. March gave way to the sunniest April, which in turn became the sunniest May ever witnessed (at least since records began in 1881). It was the fourth driest May, too. As every day dawned to another endless blue, I had a sense of Covid-19 bending time.

So many of the seasons which normally dictate our year were, in a matter of days, rendered meaningless. The football season, the fashion season, the fishing season, the wedding season, academic calendars and holiday dates, all evaporated from diary pages as if drawn in invisible ink.

Four seasons, however, remained. Their passing suddenly gained an importance that had been forgotten in the hurried turmoil of modern lives. People spoke of the scales falling from their eyes and wondered if the birds always sang this loud, or had we just started listening to them? Amid the spiralling death toll and fear of every interaction with a stranger, spring, the season of regeneration, erupted in glorious technicolour.

My lockdown road trip ended in the Derbyshire village of Eyam, where in 1665 residents cut themselves off from the outside world for eighteen months after an outbreak of bubonic plague, to prevent it spreading to the surrounding area. I interviewed residents who in some cases could trace their families back to the original epidemic and were now shielding from coronavirus in the very same seventeenth-century cottages as their ancestors once had. Standing there talking to people the agreed distance of two metres away in the threshold of the old plague cottages, rarely had I been so aware of the elasticity of our ties to the past.

I returned home to nearby Sheffield to commence my own period of self-isolation. Among the strange must-haves during that period sourdough starters, tomato plants and so on was a copy of The Plague by Albert Camus. My mum sent me one in an early Covid care parcel and reading of the fate of the people of the Algerian port city of Oran, gripped by an outbreak of bubonic plague, I was struck by similarities with our own situation. Not least, the weather. Camus wrote of the incessant sunshine weighing heavily on the plague-ridden town as the death toll crept up. The French word for weather, temps , is the same as for time, and I started to feel a strange interlocking between the two.

Weeks blended into months as I watched spring pass. Every morning before settling down to write, I took a walk through my local woods. In my garden I counted the species of birds and insects and the flowers that had come into bloom. This in itself is nothing particularly new. Since moving here with my wife three years previously, we had both always kept a close eye on life in our garden. But suddenly I was able to watch the season on a level of intimacy my peripatetic life as a journalist never normally affords.