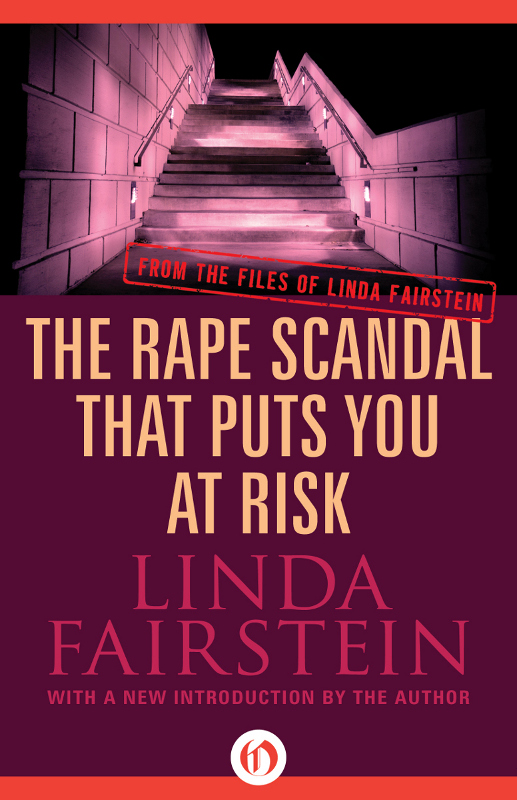

The Rape Scandal That Puts You at Risk

From the Files of Linda Fairstein

Linda Fairstein

Introduction

THE RAPE EVIDENCE KIT BACKLOG that I first wrote about in Cosmopolitans April 2011 issue continues to be a national scandal to this day. Estimates from crime victim advocacy groups and law enforcement agencies across the country suggest that there are more than 250,000 untested kits on police storage shelves, from crimes committed anywhere from one to twenty-five years ago. These kits contain potential evidence that was collected when victims submitted to medical exams following sexual assaults. But thanks to vigorous advocacy and responsible media attention to this issue, there are pockets of progress in a few cities. This confirms the need to step up the action, identify the cases, develop the DNA evidence, and submit the results to our national databank.

The case I featured, Helena Lazaros, ended well because her own efforts to get her evidence tested fourteen years after her attack resulted in the arrest of a convicted rapist named Charles Courtney. Last year, Courtney appeared in a California courtroom and pleaded guilty to the brutal crimes against Lazaro. When he finishes serving his twenty-five-year sentence in an Ohio jail for a crime he committed after Lazaros assault, I expect that he will spend the rest of his life in a California prison doing time on her case.

Three of the big backlog cities I mentioned in 2011 have really stepped up to the plate to solve this egregious problem. In 2011, Detroit (more than 11,000 backlogged kits) and Houston (more than 4,000 backlogged kits) were the first two cities awarded federal grants of one million dollars by the National Institute of Justice to analyze cold cases and determine which kits should be tested first, in hopes of getting valuable results. Detroits efforts were led by prosecutor Kim Worthy, the victim of a stranger rape when she was a law school student at Notre Dame. Four hundred kits were analyzed and revealed that most of the offenders were serial rapists, responsible for a high percentage of the long-unsolved cases. In May of this year, the first rape case from an untested kit went to trial, and the survivor of the 1997 case testified about waking up during a home invasion, with a stranger straddling her and threatening her with a gun. The jury convicted Antonio Jackson, now thirty-eight years old, of first-degree criminal sexual conduct, long after he thought hed be at risk for capture. The evidence that had languished on a dusty shelf for more than a decade matched Jacksons DNA profile in the national criminal offender databank.

Cleveland, too, has had exciting results. The 2011 movement to address more than 6,000 kits started with testing 170 of the oldest kits from the 1990s. From that sampling, thirty-six of the cases yielded useful lab results. (Not every case yields DNA evidence of value, especially with forensic techniques two decades old.) According to Cleveland Police Lieutenant James McPike, in charge of Special Victims cases, eleven of these had useful DNAand ten of those eleven cases were matched to men whose DNA was in the national databank. Those men were among the original suspects all those years ago, when the crimes were committed. These results make it clear that we must continue to press for government funding to solve these hundreds of thousands of heinous crimes and bring to justice the assailants who have rapedand raped againbecause the evidence was never analyzed, despite the cooperation of the survivors who agreed to be tested.

The Rape Scandal That Puts You at Risk

I FIRST HEARD ABOUT 31-year old Helena Lazaro last year through a colleague, and the details of her casea series of brutal rapes followed by 14 years of injustice at the hands of law enforcementleft me shocked and angry.

When Helena was 17, she pulled her Volkswagen Rabbit into a carwash one evening in her suburban Los Angeles hometown. A man approached her and asked for a ride. She said okay just to stall him, intending to drive away quickly. But he slid into the backseat, pressing a knife against her throat and ordering her to drive to specific deserted spots. At each onea parking lot, an underpass, a rail trackhe either raped her or made her perform oral sex. When he finally ran off, Helena flagged down a police cruiser.

At the local police precinct, she bravely provided a description of her assailant and detailed the assaults to investigators. Helena was then taken to a hospital, where she underwent a rape exam, during which a doctor probed her entire bodyincluding her vagina, rectum, and mouthfor physical clues the rapist had left.

This uncomfortable but important exam has been routine since the mid-1990s, when it became possible to link DNA found on a womans bodyvia semen, hair, and other biological matterto a suspect. Whats found is stored in a rape kit, a package containing envelopes, swabs, and other items to help preserve evidence.

As a former sex-crimes prosecutor, I can vouch that Helena did everything right after her ordeal: She reported her attack, endured a rape exam, and called the L.A. County Sheriffs Department regularly asking for updates on her casealthough they never once got back to her. She did this despite the constant fear that her rapist would return, since he had stolen her drivers license, which listed her address.

Two years after her assault, in 1998, she became hopeful her attacker would be found when the new FBI computer database of criminal DNA came into use. Before the database, a suspect had to be identified and DNA extracted from him before a match could be made. But now, if the evidence collected in her rape kit yielded DNA, it could be fed into a computer and matched to one of millions of DNA samples from criminals. As time passed without word from the police, Helena figured that tests of her rape kit returned no evidence or the kit had been lost.

What really happened was much more appalling. In 2009, Helena shared her story with a friend who worked at a social-services group. The friend pressed the sheriffs office on Helenas behalf to find out about her rape kit. Within a week, they got a response. Helenas kit had been tested, and the DNA evidence matched a predator named Charles Courtney, who has been in prison in Ohio since 2002 for raping a 21-year old woman in 1998.

Helena wanted answers from police as to why shed been left in the dark for so long and whether Courtney could be charged with the crimes against her. Thats where I came in. Helenas friend is my colleague at the Joyful Heart Foundation, founded by Law and Order: Special Victims Units Mariska Hargitay to help heal sexual-assault victims. After she told me about her situation, I offered to be Helenas advocate and called the sheriffs office to get the truth.

Last October, the sheriffs department admitted that Helenas rape kit had been tested back in 2003 and returned a match to Charles Courtney. In other words, crucial evidence sat around for seven years, and once it was finally linked to a predator, the police never informed Helena, who had been living in fear all that time that her assailant was out there.

Helenas story is a tragic example of the outrageous backlog of untested rape kits that has existed nationwide for more than a decade. Experts estimate that hundreds of thousands of kits remain unopened.

Behind the Backlog

Ideally, after a victim undergoes a rape exam, her rape kit should be sent to a police forensics lab, where it would be immediately tested for DNA. That DNA is then run through a criminal DNA database to see if a match is found.

Next page