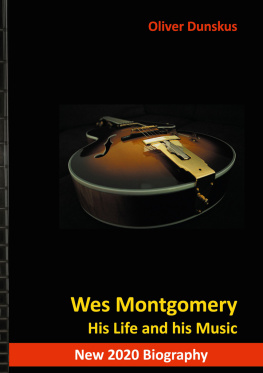

Through Others' Eyes

Published Accounts of Antebellum Montgomery, Alabama

Compiled By

Jeffrey C. Benton

N EW S OUTH B OOKS

Montgomery

Also by Jeffrey C. Benton

A Sense of Place:

Montgomerys Architectural Heritage, 18211951

The Very Worst Road: Travellers Accounts of Crossing

Alabamas Old Creek Indian Territory, 18201847

They Served Here: Thirty-three Maxwell Men

Respectable and Disreputable:

Leisure Time in Antebellum Montgomery

NewSouth Books

105 S. Court Street

Montgomery, AL 36104

Copyright 2014 by Jeffrey C. Benton. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by NewSouth Books, a division of NewSouth, Inc., Montgomery, Alabama.

ISBN: 978-1-60306-258-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-60306-259-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014949888

Visit www.newsouthbooks.com

To my daughters,

Caroline and Catherine

Contents

Editors Note on the Text

Each passage in this volume is transcribed exactly from the original source indicated at the beginning of the chapter. Misspellings, spelling variants, as well as grammatical and typographical errors follow the original sources. Punctuation varied from author to author, but all used commas more frequently than standard usage today; usage of colons and semi-colons also varied from contemporary practice. With few exceptions, errors in fact are reprinted without editorial comments.

The copies of the originals used in this volume are held by the Library of Congress or by the Special Collections, Ralph Brown Draughon Library, Auburn University. Most of the travel books are available online and at large university libraries.

Preface

T hrough Others Eyes , like its companion volume, The Very Worst Road: Travellers Accounts of Crossing Alabamas Old Creek Indian Territory, 1820-1848 , grew out of my research on leisure activities in antebellum Montgomery. In the mid-1990s, while I was compiling those accounts, I also began collecting published accounts of antebellum Montgomery itself.

It was not, however, until the summer of 2009 that I was inspired to follow through with the project begun more than a decade earlier. Both the scholars and schoolteachers participating in Slavery in Alabama: Public Amnesia and Historical Memory, a continuing education course for teachers conducted by the Alabama Humanities Foundation and the Alabama Department of Archives and History, provided the inspiration by reminding me of the power of primary sources.

In rereading the collected accounts, I began to compare memories of my own travels (unlike the writers of the published accounts in this book, I did not keep notes). Although my travels have given me perspective and a measure with which to evaluate different places, including Montgomery, my adopted hometown, they have serious limitations. I certainly have a more realistic understanding of the nine states and four foreign countries in which I have lived than I do of all fifty states and the thirty-two countries that I have merely visited.

One whirlwind visit, however, stands out: five days in Romania in 1993. I knew little about Romania before being selected from the U.S. Air War College faculty to travel to Bucharest to speak on the role of national armed forces in a liberal democracy, something foreign to the students in the Romanian War College. Unlike our four war colleges, Romanias not only had senior officers of the Romanian armed services but also parliamentarians, government bureaucrats, and representatives of the media. In addition to formal lecture hall and classroom experiences, I was dined and toured and had several hours to explore the city alone and on foot.

A significant part of what was once known as the Paris of the Balkans had been leveled by Nicolae Ceausescu in a mad failed attempt to rebuild the city on a monumental scale; Napoleon, Hitler, and Stalin came to mind as I walked. Thanks to our military mission, I was also able to spend one day in Transylvania with a University of Texas professor. We visited a fortified Saxon (German) village that had no electricity, running water, or gas. Most shocking was looking in the home of a Gypsy family who had been slaves until the fall of Ceausescu in 1989, although slavery had been legally ended in Romania in 1918. I vividly remember looking into a room that had no furniture. Its only contents were a pile of rags on one side of the room for the females and another pile on the other side for the malesand in the middle, on the floor, a hunk of raw meat with several dogs licking up the blood. The point of this extended example is this: What do I really know about Romania, even with educated and knowledgeable people helping to interpret what I was seeing and experiencingand what did most of those traveling through antebellum Montgomery really know about the city, its people, its values, and its manners?

In the Prologue that follows, I address how these limitations affected the accounts of antebellum visitors to Montgomery.

Acknowledgments

As mentioned above, I am indebted to the participants in the workshop on Slavery in Alabama organized by Alabama Humanities Foundation and the Alabama Department of Archives and History, especially to Mary Ann Neeley, who remembers more about Montgomery than others have ever heard, and Dr. Chaunda A. McDavis of Auburn University, who introduced me to James Redpath. My wife, Karen, has as usual undertaken the laborious task of proofreading the text; I want her to know that it is not a thankless task.

Prologue

Travel books were extremely popular in the nineteenth century. At least forty mention Montgomery, which, because of its location just off the Federal Road and near the head of navigation on the Alabama River, made it a natural transit point between the Seaboard States and the Gulf cities of Mobile and New Orleans.

Travel books, however, have their limitations, especially those by writers who only experienced cursory visits. Their comments tend to be mere sketches; they may capture a vague likeness of the place, but they rarely are portraits that capture the soul of the place. Consequently, the primitive state of roads, hotels, food, and the inhabitants themselves filled many inches of type. Some of those who wrote about antebellum Montgomery were famous, others were obscure; the length of the biographical comments that precedes each account indicates the authors relative prominence. Of the twenty-seven writers included in this book, only Harriet Martineau and Fredrick Law Olmsted spent more than a few days in Montgomery and present content that exhibits depth of understanding. The entertainers Noah Ludlow, Sol Smith, and P. T. Barnum may have had extended visits or visited several times, but their accounts tend to be focused on themselves and to be rather frivolous. William Howard Russell managed to observe and analyze in a short time, but then he was a seasoned reporter for The Times of London and had access to everyone from Abraham Lincoln to Jefferson Davis. Others, such as Auguste Levasseur, an aide to the Marquis de Lafayette, and Francis Pulszky, who served Louis Kossuth in a similar capacity, were on semi-official visits and would, therefore, have been insulated to a degree from an ordinary experience. James Redpath, operating at the other extreme, traveled incognito so as to be able to interview thousands of slaves.

American chattel slavery was of great interest to the Europeans and to a somewhat lesser degree to the Northerners. As the century wore on, fewer Europeans would have remembered slavery in Europe; between 1787 and 1808, French and British slavery had been abolished, first domestically, then in their empires, and finally the legal slave trade itself. Slavery began to die out in the Northern States after the American Revolutionit was deemed incompatible with revolutionary idealsand was essentially nonexistent in the Northern states as far as Northerners were concerned. So slavery had become, in the Southern phrase, the peculiar institution.