CONTENTS

Guide

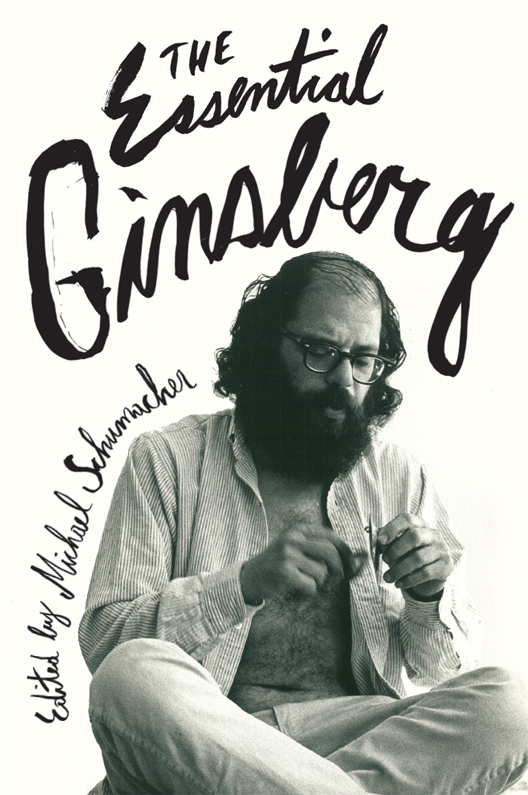

Allen Ginsberg, one of the most influential poets of the twentieth century, was such a familiar face in newspapers and magazines and on television that he was internationally famous to millions who had never read any of his poetry. He spent much of his life as an advocate for human rights, freedom of expression, gay liberation, and other causes; he was one of the early, vocal opponents of the Vietnam war. He was a teacher, Buddhist, essayist, songwriter, photographer. One of the core members of the Beat Generation, he slipped easily into a position of leadership among war protesters, college students, Flower Power hippies, and political radicals. It occurs to me that I am America, he wrote, semihumorously, in one of his early poems, but he wound up being much more than that. Poet/editor J. D. McClutchy summed up Ginsbergs influence in one simple statement published in the New York Times following Ginsbergs death in 1997: His work is finally a history of our eras psyche, with all its contradictory urges.

Given the man Ginsberg became, its hard to believe that, at one time, people feared for his psychological well beingeven for his survival. Louis Ginsberg, Allens father, worried that he might be following the path of his mother, Naomi Ginsberg, a bright but troubled schoolteacher who spent much of her adult life institutionalized for mental disorders. William Carlos Williams, Allens early mentor and sponsor, expressed his concern when, in his introduction to Howl and Other Poems, he wrote: I never thought hed live to grow up and write a book of poems. His ability to survive, travel, and go on writing astonishes me. That he has gone on developing his art is no less amazing to me.

How did Allen Ginsbergs life develop from his difficult youthful days to a point where he would be honored for his intellectual and artistic mind? This book, aside from assembling selections of Ginsbergs most memorable poetry, prose, music, and photographs, will attempt to answer this question. Ginsberg described his work as a graph of my mind. He spent a lifetime trying to expand his own consciousness, employing everything from drugs to meditation to provide different inducements to that expansion. He believed that his writings, music, and photography might be useful (as he liked to put it) to readers, whether that usefulness came from art in the strictest sense, from the way his work pinpointed precise moments in history, or from assuring others that they were not alone, that their thoughts and longings were part of a universal consciousness greater than any individuals.

Here, in a single volume, you will find a sampling of the range and topography of Ginsbergs mental landscapes. There are the long, rhythmic lines found in Whitman, one of Ginsbergs most significant influences; the prophetic voice of William Blake, whom Ginsberg had heard in a series of auditory visions in Harlem in 1948; the bop prosody of Jack Kerouac, novelist and poet and enduring Ginsberg friend. There are dream notations, travel journals, autobiographical fragments, chatty letters to friends, details of his expulsions from Cuba and Czechoslovakia in 1965, photographs of the important people in his lifeeven the testimony he gave to a U.S. Senate subcommittee. He writes in great depth about the creation of Howl (1955) and Kaddish (1959), two masterworks, and speaks of how his meditation practices informed and added texture to his work. From the prose poem, The Bricklayers Lunch Hour, to the rhymed lyrics of Starry Rhymes, one of Ginsbergs final poems, the reader is introduced to one of the most compelling minds that the American literary world has ever encountered.

Kaddish, Ginsbergs moving elegy to his mother, goes beyond providing the details of Ginsbergs difficult youth and his familys dealing with Naomi Ginsbergs mental illness. The poem, like Howl, offers a powerful backstory to Ginsbergs lifelong empathy for the disenfranchised, the embattled pilgrims, the souls wandering in uncharted spacethe beat. Ginsbergs empathy is evident in Portrait of Huncke, a fragment of a large 1949 journal entry, in which a nave young Allen Ginsberg takes pity on a homeless street hustler and invites him into his home, only to be dragged into his schemes and ultimately a run-in with the law. His 1979 letter to Diana Trilling, essayist and wife of one of his most trusted college professors, Lionel Trilling, is an account of an incident that led to Ginsbergs being expelled from Columbia University. Then there are accounts (in his letter to John Clellon Holmes and in his Paris Review interview) of his 1948 Blake visions, which alarmed his family and some of his friends, and caused them to wonder if he was losing his mind. These visions started Ginsberg on a fifteen-year quest to discover and expand the unexplored regions of his mind.

And this was all before he celebrated his twenty-third birthday.

For all the difficulties in his late-teens and twenties, Ginsberg never abandoned his extremely self-disciplined writing of poetry. The early work, derivative of poets he studied in high school and college, evolved rapidly after he met Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady, and othersall of whom served as mentors in his intellectual and creative development. The Bricklayers Lunch Hour (1947) and The Trembling of the Veil (1948), two poems fashioned from journal entries, pleased William Carlos Williams when the older poet saw them, and with Williamss encouragement, Ginsberg shed the skin of his youth. He grew at an astonishing rate, especially in the mid-1950s, after he moved to the West Coast, met Peter Orlovsky, became involved in what became known as the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance, and wrote such classics as Howl, A Supermarket in California, America, and others that were included in Howl and Other Poems, his first published collection of poems. Ginsbergs lengthy explanatory letter to Richard Eberhart on the writing of Howl proves, if there was any doubt, that Ginsbergs work was the result of a convergence of acquired knowledge, a continuous process of self-discovery, experience, and creative courage.

The Beat Generation phenomenon, coupled with the attention Ginsberg garnered from Howl and its successful defense in a celebrated obscenity trial, changed Ginsbergs life. He enjoyed celebrity status, his poetry was in constant demand, and the press sought his opinions on just about every imaginable topic. Ginsberg basked in the limelight, and he used the interview and occasional essay to expound on a wide spectrum of subjects, from literature to politics. He grew up listening to his parents bicker over politics and had nurtured an interest in political and social issues dating back to his teenaged years, when he and his older brother, Eugene, wrote letters to the editors of area newspapers, including the New York Times. Fame became Ginsbergs soapbox, and from the 1960s he was not shy about expressing his views on censorship, psychedelic drugs, gay liberation, international politics, Vietnam, and the suppression of individual freedoms. Poems such as Wichita Vortex Sutra and Plutonian Ode smoulder with Ginsbergs passionate feelings about the war in Vietnam and the proliferation of nuclear power. A calmer, yet still firm and reasoned, approach can be found in his senate subcommittee testimony on LSD or his statement on censorship. His accounts of his 1965 misadventures in Cuba and Czechoslovakia, found here in a previously unpublished journal entry and in his letter to Nicanor Parra, are exceptional supplements to Kral Majales, Ginsbergs poem on his election as King of May and subsequent expulsion from Czechoslovakia.