Table of Contents

Guide

Page List

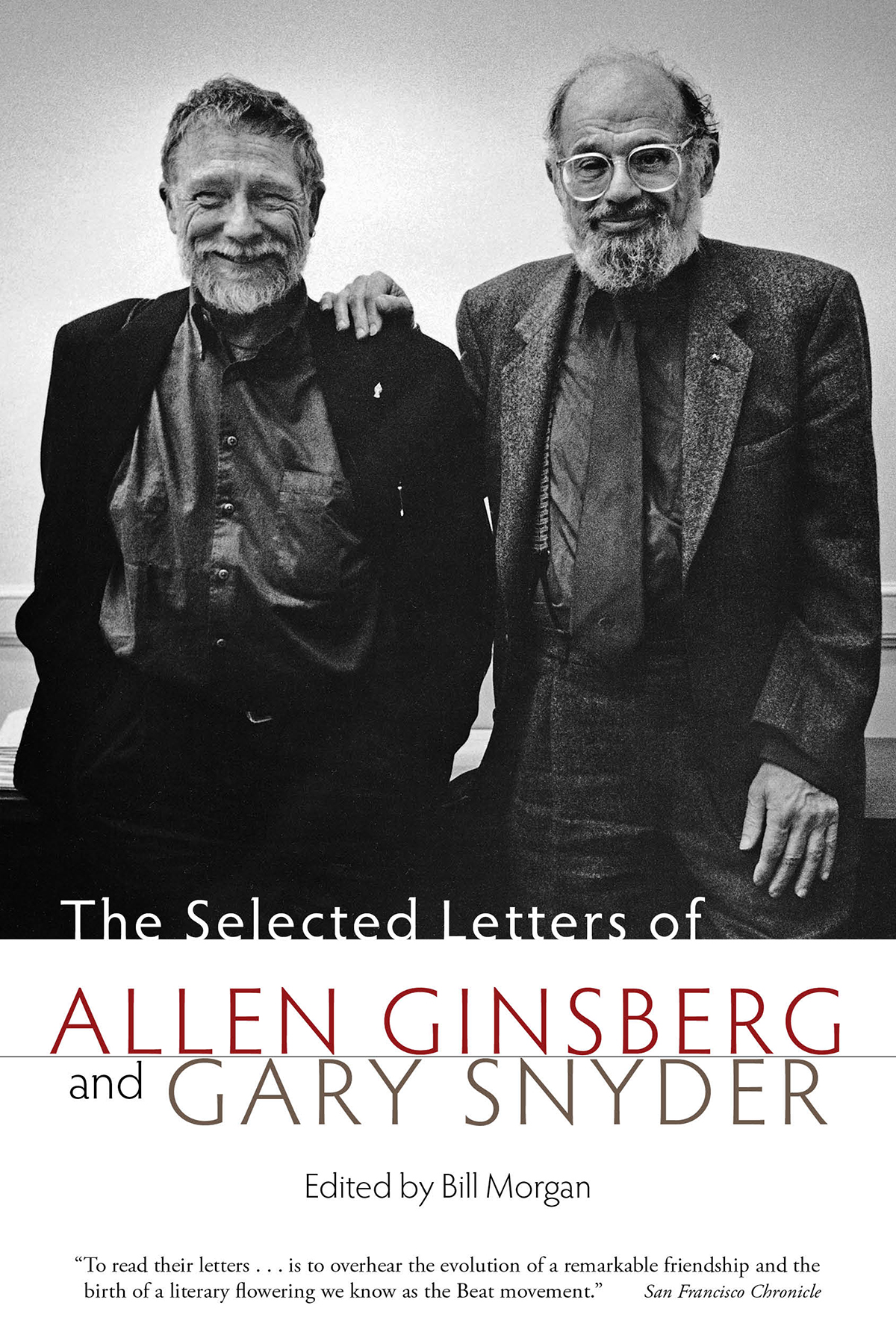

The Selected Letters of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder

Contents

During the twentieth century, letters were a literary form that nearly everyone practiced. In todays world of cell phones, text messaging and email, it all seems quaint and old-fashioned, but in the days before inexpensive long-distance telephone service became commonplace, the main avenue for communication was the written word.

Gary Snyder and Allen Ginsberg were no exception. After they met in the summer of 1955 they kept in touch by a correspondence that lasted through the next forty years. Both faithfully saved their friends letters even as they traveled around the world. When the editorial director of Counterpoint books, Jack Shoemaker, discovered that their letters still existed, he asked me to edit them into a book. I knew of Ginsbergs letters from my earlier work on his biography, but I was surprised by the wealth of information that Snyders side of the correspondence provided. Together they reveal a friendship that helped shape American literature, environmental concern, and spiritual discovery in the second half of the twentieth century. It was through Snyders studies in Japan and Ginsbergs continual proselytizing that so many people in the West came to discover Eastern spirituality and Buddhism. They were the poet/magnets to whom other like-minded people were attracted after the pair appeared onstage together as hosts for the first San Francisco Human Be-In of 1967. That event heralded the Summer of Love that changed midcentury popular culture forever. Through their example they passed along a knowledge of Eastern meditation practice to countless members of the youthful counterculture during the following decades. Without them would the sixties have unfolded in the same way?

The letters that follow are arranged chronologically. In the few instances where the editor has omitted extraneous passages, an ellipsis [... ] is inserted in the text. Anything that appears within square brackets [ ] is an editorial note and does not appear in the original letter. There are a few gaps in the sequence where (for whatever reason) the letters from one or the other poet could not be located. Editorial notes have been added in an attempt to provide information that might have been lost with those letters. Footnotes give some background on people, events, and unfamiliar terms. In the case of East Asian names, scholarly practice has been followed, giving the surname entirely in uppercase letters to distinguish which is which. The family name always comes first and the given name second for names from China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam. In Southeast Asia and India the family name comes second as it does with Western names.

To clean up the text, phone numbers, some addresses, and irrelevant postscripts have been eliminated. Copies of poems, form letters, and other materials that were originally included with letters are generally not reproduced. In the case of poems, those are readily available in collections of Snyders and Ginsbergs work.

Because so many Asian terms were used within the letters, I have relied heavily on dictionaries for definitions and these can often be found in the footnotes following the first use of the word. In addition to standard dictionaries, I am indebted to the editors of The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen (Shambhala, 1991), The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion (Shambhala, 1994), and Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (Thames and Hudson, 2002). However, the most important resource used in the preparation of this book was a living one. Gary Snyder was always willing to be of help during the editorial process. In spite of his busy schedule he answered my every question quickly and thoroughly. It was through his knowledge and experience that many of the letters were deciphered and interpreted. Without his help, this book would have lacked the focus it now has.

Behind the scenes, many people have graciously helped during the preparation of this book. In addition to the patient assistance of Gary Snyder, the people at the Allen Ginsberg Trust were always there to lend support. Peter Hale, who is the unheralded master of all things Ginsberg, worked tirelessly on every query I posed him. He, along with co-trustees Bob Rosenthal and Andrew Wylie, supported this project from the beginning. The extraordinary staff at Counterpoint Press, Jack Shoemaker, Laura Mazer, Adam Krefman, Abbye Simkowitz, and Julie Pinkerton, conceived the project and saw it through to the final stage of this handsome production. All of Gary Snyders letters are preserved with the Allen Ginsberg Papers in the Special Collections Department of Stanford University and Allen Ginsbergs letters are available in the Special Collections Department of the University of California at Davis. The librarians of those two institutions gave their unreserved support to this project.

Acknowledgement is also due to those who gave this editor an extra measure of help along the way: Jack Hagstrom, Joanne Kyger, Peter Orlovsky, John Suiter, and especially to my most steadfast supporter, Judy Matz.

BILL MORGAN

Allen and I came from the far ends of the nation. I was from the German and Scandinavian working farmer/logger/fisherman world of pre-WW II Puget Sound, Allen from the New York City Immigrant Left. We met in a backyard in Berkeley, and again in Kenneth Rexroths wood-floored apartment in the foggy Avenues zone of San Francisco. The fall of 1955 was the end of graduate school for both of us. We argued a lot and were not easy on each other. I made him walk more, and he made me talk more. It was good for both of us. In that first Bay Area eight months, he and his buddy Jack Kerouac managed to push the already strong but reticent Bay Area poetic culture into public light, with a deliberate intention for some sort of transformation, first literary and then social.

We hitchhiked to the Canadian border and back in the middle of winter giving uninvited readings in Portland and Seattle. I left the coast in May of 1956 for a long stay in Japan (sailing by passenger-freighter), and that was the beginning of our correspondence. Living in different parts of the world as we did for most of the later years, we stayed in touch the old way, with letters. Allen was remarkable for his transgressive sanity. I swung between extremes of Buddhist scholar and hermit nerdiness and tanker-seaman craziness at bars and parties. I sense, reading these letters again, that our mutual respect continued to grow.

A lot of the time we were just working out the details, trail routes, land-management plansand thats what the real work is. His apartment on the lower East Side, my hand-built house at the end of a long dirt road in the far far West, were our hermitages, base camps, and testing grounds. It was all just dust in the wind, but also, the changes were real.

GARY SNYDER

26.IX.08

EDITOR S NOTE : Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder were both living in Berkeley, California, during the summer of 1955. Acting as a literary gadfly, poet Kenneth Rexroth suggested that Ginsberg and fellow poet Michael McClure organize a poetry reading that was to feature young, unknown Bay Area writers like themselves. Rexroth had even gone so far as to offer a list of aspiring poets he felt deserved exposure. On that short list was the name of Gary Snyder. In mid-September Ginsberg arranged to have dinner with Snyder. Coincidentally it was on the same day that Ginsbergs close friend Jack Kerouac arrived in town from Mexico. Snyder and Ginsberg hit it off immediately, and the Six Gallery reading, as the October 7, 1955, event became known, was a tremendous success