Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

2017 by Robert Inchausti

The Credits section on constitutes a continuation of the copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

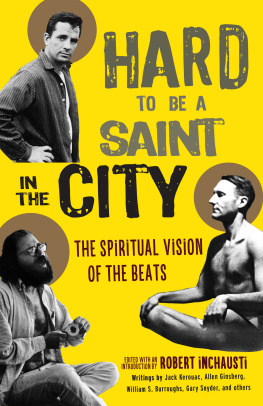

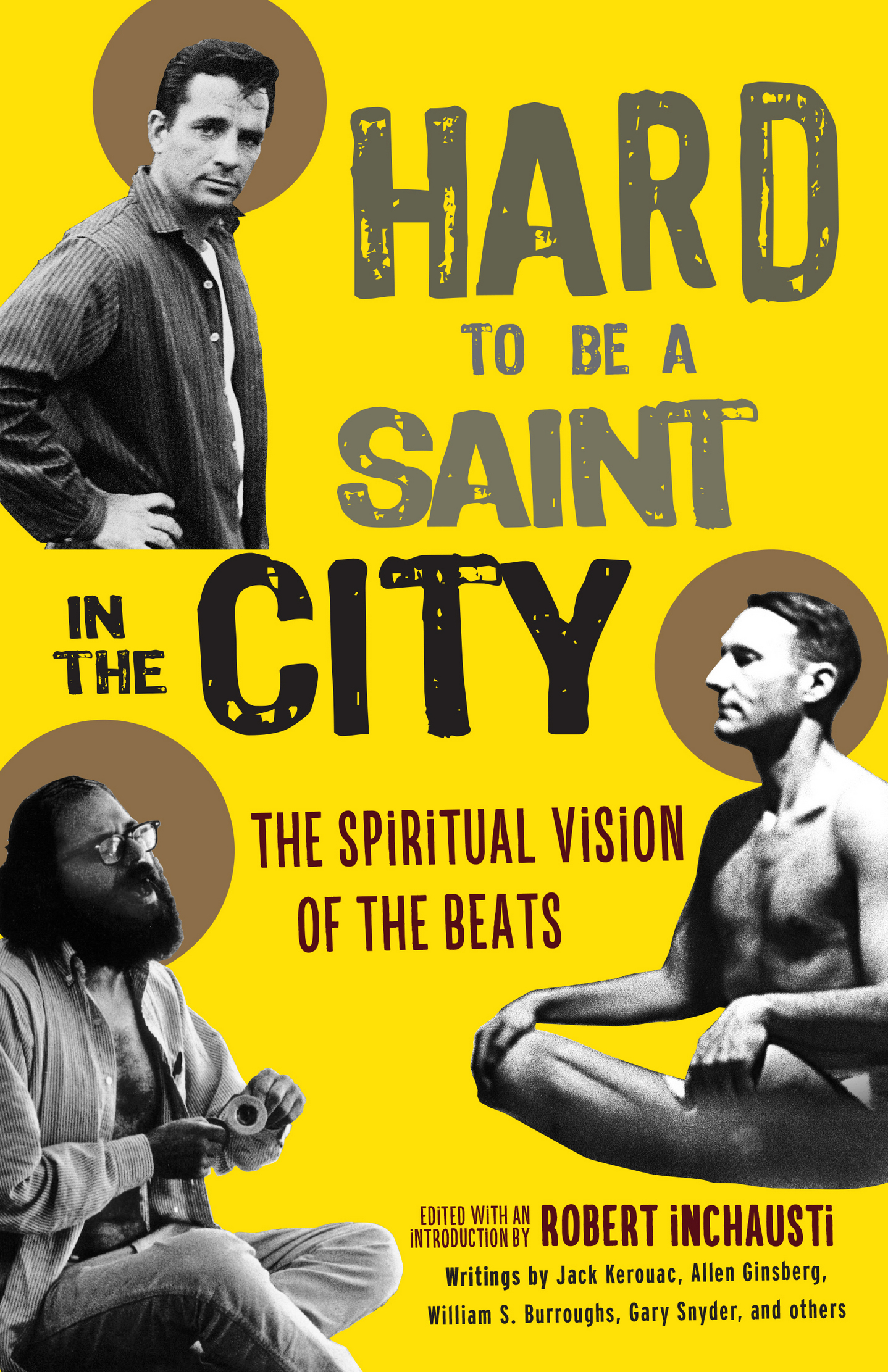

Cover design by Jim Zaccaria

Cover photos: Jack Kerouac: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Gift of P / K Associates, 84.1008 Robert Frank; Allen Ginsberg: by Larry Keenan, courtesy of Pace/MacGill Gallery New York; William Burroughs: by Allen Ginsberg LLC, Corbis Premium Historical, gettyimages.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Inchausti, Robert, 1952 editor.

Title: Hard to be a saint in the city: the spiritual vision of the Beats / edited by Robert Inchausti.

Description: First edition. | Boulder: Shambhala, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017020875 | ISBN 9781611804171 (paperback)

eISBN9780834841093

Subjects: LCSH: Beat generationPhilosophy. | Literature and SpiritualismUnited StatesHistory20th century. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / American / General. | BODY, MIND & SPIRIT / Spiritualism. | RELIGION / Buddhism / Zen (see also PHILOSOPHY / Zen).

Classification: LCC PS 228 .B 6 H 36 2018 | DDC 818/.5409dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017020875

v5.2_r1

a

Contents

Editors Introduction

I am Buddha come back in the form of Shakespeare for the sake of poor Jesus Christ and Nietzsche. J ACK K EROUAC

I have tried many times to share my admiration for Jack Kerouac with my Catholic and Buddhist friends. But as a rule, his reputation as a know-nothing Bohemian so precedes him that they simply refuse to take me (or him) seriously. And I can understand their skepticism. His most famous novels are written in a self-invented bop-spontaneous prosea jazz-inspired meld of improvisation and stream of consciousness. And the stories he tells are largely autobiographical accounts of his interactions with various social misfits and outsiders. So when Kerouac says I have nothing to offer anybody but my own confusion, it is easy to take him at his word.

Yet serious readers should not be so easily fooled. Kerouacs Dionysian revels and Dostoyevskian reflections lend weight to his work rather than detract from it. And there are other reasons to consider Kerouac among the most important American spiritual writers of the last half of the twentieth century. Not only did he refashion American Transcendentalism through the modern idioms of jazz, haiku, and memoir, but he also inspired a small army of imitators and disciples who carried his literary project far beyond anything he could have accomplished on his own.

Ethan Hawke (the actor) once said that Kerouac made it cool to be a thinking person seeking a spiritual experience. And there is no doubt that the writers Kerouac knew and inspirediconic figures like Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Gary Snyder, and Michael McCluredid just that. And taken together they have produced one of the most profound bodies of spiritually oriented literature since the American Renaissancewith Kerouac playing Emerson to Ginsbergs Whitman and Snyders Thoreau.

At the heart of this re-visioning of American letters resides Oswald Spenglers eccentric, magisterial opus The Decline of the Westa book that greatly influenced both Kerouac and Burroughs and provided the vocabulary and conceptual framework for the very idea of a Beat Generation. Central to Spenglers thesis is the notion that all cultures begin as cultsspiritual enterprises designed to convert the zoological struggle for survival into a pursuit of various high ideals. In India, for example, life is organized around the transformation of the interior life; whereas in the modern West it is organized around taming nature to produce the greatest good for the greatest number.

As cultures age, Spengler observed, they inevitably decline into civilizations, which means that the mechanical operation of their institutions come to replace the idealistic zeal that fueled their collective endeavors in the first place. Altruism gives way to the imperatives of practical life, and over time everyday existence becomes less and less of a heroic adventure and more and more of an irreligious routine. This decline can go on for hundreds and hundreds of years. In fact, according to Spengler, most civilizations spend the greater part of their life spans in decline.

And yet, Spengler also noted that a second religiosity often emerges in the twilight of waning civilizations when the old symbols take on a new meaning and renewed vitality. These cultural revivals are normally short-lived, but during them a more inclusive interpretation of the founding tradition takes place that serves as a preview of the next great world civilization waiting in the wings of human history. A good example of this can be seen during the Axial Age when the Buddha refurbished what had become a rigid Hindu religious system into a method for universal Enlightenment, or when Elijah united the twelve tribes of Israel around a more inclusive, visionary interpretation of the Mosaic Covenant.

The Beats came of age just as the United Statesin order to win a world war against its fascist enemieshad reorganized itself into a security state. The ensuing Korean War only increased this move away from democratic values, and as a result, the Beats found themselves, like every American coming of age in the late forties and early fifties, caught between a new mass-mediated consumer society and their own aspirations for a life of personal freedom and self-expression. As Norman Mailer put it in The White Negro, postwar America was rapidly dividing itself between the hip and the square, between the status-seeking Mad Men in their grey flannel suits and Allen Ginsbergs angel headed hipsters seeking the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.

Spengler called these idealistic culture-bearers living on the margins of civilization the fellaheen. Originally a derogatory term used to describe displaced Egyptians living within the Roman Empire, the fellaheen represented a more inclusive interpretation of the prevailing cultural myths, images, and memes than the conventions of the prevailing civilization allowed. And although Spengler himself was an archconservative who saw the fellaheen as essentially powerless retrogrades doomed to fail, the Beats admired their sincerity and the deep piety that filled their waking-consciousness with the naive belief that there [was] some sort of mystic constitution to reality.

When Allen Ginsberg began Howl with the memorable line I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, he was speaking for those fellaheen idealists not yet recognized as a progressive force in contemporary historya fellaheen avant-garde, as it were, whose story had already been told in six unpublished novels by Jack Kerouac.

The Beats saw themselves as living in the middle of two very different historical epochs. On the one hand, they spoke for a new, international spiritual community coming into being and, on the other, for an old-fashioned candor and tenderness seeking expression within the new regime. When Kerouac admitted that I had nothing to offer anybody but my own confusion, he wasnt being nihilisticjust offering an honest, hip characterization of what it felt like to be caught between cultural idealism and civilized order. As one might surmise, not many grasped the Spengler meta-historical perspective behind the Beats revolt, and so the intellectual sources of their work remained mysteriouseven to many of the Beats themselves.