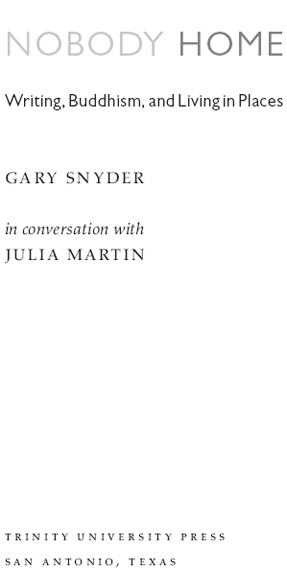

Published by Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright 2014 by Julia Martin and Gary Snyder

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

978-1-5953-4252-2

Cover design by Rebecca Lown

Book design by BookMatters, Berkeley, California

Cover art: Gary Snyder, Black Rock Desert, Nevada, courtesy of the Gary Snyder Archive

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 39.481992.

CIP data on file at the Library of Congress

18 17 16 15 14 | 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

GARY SNYDER

JULIA MARTIN

Crossing the equator

curving over the Atlantic ocean space, southnorth, westeastCape Town and Table Mountain, Namaqualand, Kalaharito Cape Mendocino, Shasta, Black Rock desertJulia and I have tossed our paper airplane letters toward each other now for over thirty years, mostly swooping ok down

To compare our wild / tame female / male scholar / artist parent / wanderer

tricks with each other. All on the path of walking, writing and sitting. Ive learned so much from her. And I love this neo-Gondwanaland we share. Its not over yet.

GARY SNYDER

JULIA MARTIN

One morning in 1984, a letter posted on the other side of the world clacked through the flap of our door in Cape Town. It was from Gary Snyder, a warm response to questions about his writing. I was a graduate student at the time and had been reading his work after a friend gave me a copy of A Range of Poems. That first letter was the beginning of a long, long-distance friendship and an ongoing conversation.

It started as an intellectual exchange and became an exploration of practice. As a young person living in a society demarcated by the paranoid logic of apartheid, it was refreshing to meet the spaciousness of Garys way of seeing. His delight in wildness. Poems opened up the idea of social justice to include nonhuman beings and the living world. The truly radical realization that things are not things but process, nodes in the jeweled net. And in all this a tendency simply to walk out of the narrow prison of dualistic thought. Over the years, what has kept on bringing me back to Garys writing and to our conversation is his steady articulation of this vision in practice: Buddhist practice, the practice of writing, of being a householder, of living in places.

This book puts together three interviews and a selection of letters from around thirty years. During this time many things changed decisivelyin our personal lives, our local environments, and the worldand these changing conditions are the backstory for an evolving dialogue. When Gary suggested publication and I read it all again (or what I could find), I was filled with a sense of deep gratitude. And of poignant immediacy. Transience. As he describes it in a poem called One Day in Late Summer:

This present moment

that lives on

to become

long ago

We recorded the first interview, Coyote-Mind, in 1988 at Kitkitdizze, Garys home on the San Juan Ridge in the Sierra Nevada. It was a hot day in late August, and Carole Koda, his new partner, sat listening throughout. We talked about writing, about Buddhism, and about community, bioregion, and place. At the time, my take on these was strongly inflected by ideas about gender and the political. After all, where I came from, we were living under a dangerously repressive State of Emergency, and everyone was tuned to ideology. Returning to that dialogue now, I see how often I missed a chance to look deeper because of an attachment to my prepared questions. But Gary responded cheerfully to whatever came up, and the result is quite a far-reaching discussion. Decades later, his position from that time remains prescient and lively. As he put it to me then, in his writing the political involves a poetic politics in which what you launch are challenges and suggestions that dont make sense, or dont begin to add up, for a long, long time.

The next interview took place nineteen years later. Gary had since published some important books, including the masterworks Practice of the Wild (1990) and Mountains and Rivers Without End (1996). He now spent much of his time at Kitkitdizze looking after Carole, who was ill with cancer. On the other side of the world, I had written a doctoral thesis on environmental literacy and given birth to twins. In the United States, George W. Bush had entered a second term of office in the wake of 9/11, while in South Africa the long dark era of legislated apartheid had ended in 1994 when we all became citizens of a new democracy. As for the state of the earth, the Worldwatch Institute had declared the 1990s the decisive decade for environmental change, but the local-global crisis of environment and development was becoming ever more desperate.

What made this second interview possible was the curious business of international academic conferencing. On my last visit, Gary had given me a heap of papers, among which was the unpublished text of an essay by Cheryll Burgess (later Glotfelty) about something she called ecocriticism. Within a few years, the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment (ASLE) was launched, and with it, the beginning of a new critical tendency. By the time Gary and I attended the huge ASLE conference in summer 2005, the organization had become professionalized. He was scheduled to be a keynote speaker and suggested I join him. Do a paper.

This time we sat in his hotel room in Eugene, Oregon, and spoke about suffering and the present moment. Carole was too ill to travel, and the sadness of her absence was palpable. Danger on Peaks had appeared the previous year, so far Garys toughest and most tender response to the suffering of sentient beings. So we talked about its story of the vow he made as a teenager to fight destructive powers, after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He laughed, I could say, Well I tried. And it didnt work, did it? Ive been living my life by this and I guess it didnt come to anything. In fact its worse than ever! Then he went on to speak about healing, compassion, and the female Buddha Tara. The conference program was packed, and there were many demands on his time. But within the small space we had, the conversation was open, intimate, and meandering. We called it The Present Moment Happening.

The third interview, Enjoy It while You Can, was recorded at Kitkitdizze once again. It was autumn 2010, four years since Caroles death and a few months after Garys eightieth birthday. He spoke about the experience of nearing the Exit, and about nondualism and impermanence, while his dog Emi interrupted things occasionally for a lick or a pat. This most recent talk was probably our most serious. It was also the most playful. When I asked about old age, sickness, and death, he said, Enjoy it while you can! Because soon you wont even have that. As we worked through the transcript afterward, the main question was how to record repeated laughter without making the text repetitive. We decided to leave out all markers. The reader would have to pick it up.

Next page