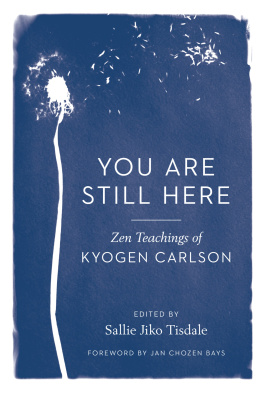

S HAMBHALA P UBLICATIONS , Inc.

.

Cover design: Kate E. White

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For more information please visit www.shambhala.com. Shambhala Publications is distributed worldwide by Penguin Random House, Inc., and its subsidiaries.

Names: Tisdale, Sallie, editor.

Title: You are still here: Zen teachings of Kyogen Carlson / edited by Sallie Jiko Tisdale; foreword by Jan Chozen Bays.

Description: First edition. | Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references.

Subjects: LCSH: Zen Buddhism. | Carlson, Kyogen.

FOREWORD

I am delighted that talks given by Roshi Kyogen Carlson are being published. When he died unexpectedly, in 2014, my husband and I lost a very dear friend. The world lost a true teacher of Dharma. It is wonderful that his teaching can still be heard.

Kyogen was a thoughtful person, often pondering for days or weeks questions that piqued his curiosity. These were his personal koans. Personal koans are the best sort. The classic koan often begins with A monk in all earnestness asked The words in all earnestness speak to weeks, months, or years of pondering a question that has become deeply lodged, like a ticking time bomb, in your body-heart-mind, a question that cannot be released until it opens of itself. Opens of itself includes hours on a cushion in the meditation hall, hours spent clearing the mind. Once clear, the nagging question can be dropped in, and, like a stone dropped in a still pool, ripples spread and intersect, and sometimes, sometimes, everything turns inside out.

Kyogen describes this process. He had worked for a while on a koan, dropped it, and then, years later, At the end of the day, as it was getting dark, the lights in the cloister came on. It was a funky thing, this cloister, a covered walkway that wound through a lot of incense cedar and beautiful trees, with each section of the cloister lit by little wrought iron lamps. All of a sudden the lights came on and I immediately understood the koan.

There is a reluctance to talk about spiritual openings among Zen practitioners, concern about aggrandizing or concretizing these experiences, setting a goal the student then strives for. There is also endless curiosity among Zen students about these glimpses. Despite the fact that at Zen Center of Los Angeles, where I trained, we were warned not to read about enlightenment experiences, the copies of The Three Pillars of Zen in the library would automatically fall open to the well-thumbed pages of enlightenment stories of both Japanese and Western students. In several of the talks in You Are Still Here, Kyogen speaks with appropriate delicacy about his own experiences of awakening, the sudden overturning that can emerge from long hours of dedicated gradual practice.

He also understood that enlightenment experiences are not the end, but a tentative beginning to the rest of our life of practice, of dwelling in One Mind while meeting things just as they are, as they come forward. As Kyogen puts it, We transform samsara into nirvana[by] functioning in the world from unconditioned space.

Kyogen was an innately kind person. He could be strict, clear, and even stern in his admonitions, but what he said was always supported by a foundation of love. And humor. If enlightenment is composed of equal parts wisdom and compassion, he added what I think is absolutely the test of true awakening: a silly sense of the absurdity of the predicament of being born as a human being who is trying to rediscover what they have always had, searching for what is hidden in plain view and what turns out to be so simple it cannot be believed. To add to the absurdity, some of us become Zen teachers and spend decades, as Kyogens root teacher, Jiyu Kennett Roshi, put it, selling water by a river.

When my husband, Hogen, and I left the Zen Center of Los Angeles more than thirty years ago to move to Oregon, as our rental truck lumbered its way down the hills from California and into Portland, I heard a remarkable event on the radio. A Zen priest was appearing before the Portland city council, calmly answering questions about what Zen folks actually do. When asked about the sounds that might emanate from the proposed temple, the priestKyogenrang a lovely bell. The council seemed charmed, and I thought, Well have friends in Portland! Which turned out to be true.

For many years Kyogen and his ordained wife, Gyokuko, and Hogen and I met, able to freely discuss the frustrations and the joys, the disappointments and small victories, the sorrows and the hilarious events inherent in the vows that compelled us to dedicate our lives to the strange job of establishing Zen centers and teaching Dharma. Kyogen and Gyokuko were what is called in the Christian tradition equally yokedthat is, pulling the same spiritual cart in the same direction. Their love and respect for each other was evident. Once we were at a Zen conference, and as my also equally yoked husband and I settled into bed I heard a pleasant steady murmur from the adjacent bedroom. The next morning I asked the Carlsons about it and found that they had a sweet habit of reading to each other every night before they fell asleep. They had read many books together in this way.

As you will discern from bits and pieces in these talks, Kyogen and Gyokuko experienced tough training under their teacher, Jiyu Kennett Roshi, and even tougher times after they were sent out to teach at a center in Portland. I was moved by their respect for their root teacher, evident as they struggled with her decisions to remove outlying centers authority to make everyday decisions such as writing and publishing their centers newsletter, and her demands that married couples become celibate. Kyogen was able to describe these difficulties clearly, while maintaining love and appreciation for all he had learnedand unlearnedfrom Kennett Roshi. A good teacher will challenge you by seeing further than you can, and seeing into your koan in ways you might not want to see, he said. But just as you face your own limitations and flaws, so too you face the limitations and flaws of the teacher. I do not love my teacher any less or respect her any less for having seen herall of herclearly. On the level of Dharma, what I gained from my relationship with Kennett Roshi is beyond any possible measure. The cost of this is also beyond measure. One has to be willing to sacrifice everything and jump beyond all knowable boundaries. This balanced, wide view is what led him into years of warm and respectful but honest dialogue with a conservative Christian minister.