ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the editors and publishers of the following journals and magazines in which some of these interviews first appeared: Berkeley Barb, City Miner Magazine (Issue #12, P.O. Box 176, Berkeley, CA 94701), East West Journal, Espejo (Spring 1974, Vol. XII, No. 2, Southern Methodist University), Field, Io/ 12 (Earth Geography Booklet No. 1), Literary Times, New York Quarterly, The Ohio Review (Vol. XVIII, No. 3), Plucked Chicken, Road Apple Review, and Western Slopes Connection.

Acknowledgment is also given to the following for the use of excerpts in the section Some Further Angles: Conversations: Christian and Buddhist by Dom Aelred Graham (Copyright 1968 by Dom Aelred Graham; reprinted by permission of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.), Mountain Gazette, Poetry Nippon 21, River Styx 4 (1979), and Wind Bell (Vol. VIII, Nos. 1-2, Fall 1969, published by the Zen Center).

The editor would like to give special thanks to Peggy Fox of New Directions for her care in helping put this book together.

FOR KAI, GEN, AND DAVID

A NOTE FROM GARY SNYDER

I would like to thank the men and women who provided warm rooms and tea, and then posed questions and elicited information. This book is a product of the interaction of many minds. In particular I would like to acknowledge the creative and deliberate interviews by Peter Barry Chowka and Paul Geneson, interviews in the course of which I learned things.

Without the energy of my collaborator-editor, Scott McLean, these papers would have remained scattered through the periodicals. Thanks to Scott and Patricia McLean.

Finally I would like to thank the people who transcribe tapes. Its slow, tedious work, but without their labor, our attempts to capture the spirit of the moment and the freshness of the oral context, and then put it on paper, would come to naught.

INTRODUCTION

In 1969 Gary Snyder published a collection of journal excerpts, reviews, translations, and essays under the title Earth House Hold. The materials collected covered a fifteen-year period, spanning the years Snyder spent doing forest service lookout duty in the Cascade Mountains of Washington State (195253) to his marriage with Masa Uehara on Suwa-no-se Island in 1967.

Thematically and structurally the interviews and talks gathered in this volume complement and extend the positions taken in Earth House Hold. A line can be traced in the earlier prose collection from Snyders first statements on poetics in the Lookouts Journal to the essay Suwa-no-se Island and the Banyan Ashram, celebrating a sense of community that has been lost all too long. A similar line can be followed in The Real Work, from Snyders comments on the complementary nature of inner and outer realities explored in his poetry to the talk Poetry, Community, & Climax. But whereas the relationship between poetry and community was only sketched out in the later essays of Earth House Hold, it becomes the focal point early in this collection, as poetry is seen more and more by Snyder to be a binding force in the fabric of community life.

Gary Snyders poetry has continued a tradition first pursued in late eighteenth-century Romantic thought and carried on in American literature most notably by Thoreau: a belief that the outer and inner life correspond and that poetry is the

But if Snyders work follows this thread in European and American literature, the bases for his poetry lie elsewhere: in oral traditions of transmission, in Chinese and Japanese poetics, and in the ancient and worldwide sense of the Earth Goddess as inspirer of song.

Snyders early work in Riprap was directed toward getting down to a flat surface reality, to break what William Carlos Williams called the complicated ritualistic forms designed to separate the work from reality.

In reaching that absolute bottom transparency, Snyders meditative poetry has taken two directions. One is toward a short lyric that pushes up against an edge of silence, an ellipsis where the silence defines the form and substance. In a number of these poems (Pine Tree Tops is a good example) the texts represent arrested phenomena, and the poems become, as Donald Wesling says in a related context, like the objects of modern physics,... at once product and process. These poems are small knots, whorls in the grain, a bit of stored energy that draws the reader/listener at the end of the poem to follow out in his or her mind the pathways marked.

The second form Snyders meditative poetry takes is the long poem that begins in the everyday world but then spirals up from that area, working on more mythological and archetypal The poems in Myths & Texts and in sections of Mountains and Rivers Without End touch on the most basic, deeply felt mythological ground, and they do what myth has always done: they give us some access to the intense instance of our lives in the vast series of interrelationships established by the figures, events, and images of the myth.

All of Gary Snyders study and work has been directed toward a poetry that would approach phenomena with a disciplined clarity and that would then use the archaic and primitive as models to once again see this poetry as woven through all parts of our lives. Thus it draws its substance and forms from the broadest range of a peoples day-to-day lives, enmeshed in the facts of work, the real trembling in joy and grief, thankfulness for good crops, the health of a child, the warmth of the lovers touch. Further, Snyder seeks to recover a poetry that could sing and thus relate us to: magpie, beaver, a mountain range, binding us to all these other lives, seeing our spiritual lives as bound up in the rounds of nature.

Snyders concerns are, as Luis Ellicott Yglesias recently noted, archaic in the primal sensea going into the deep past not to escape or to weep with loud lamentations, but to see whether with the help of the earth-lore that is all forgot it might be possible to open life to a more livable future.

The anthropologist Stanley Diamond has stated that the sickness of civilization consists... in its failure to incorporate (and only then) to move beyond the limits of the primitive. Taking up the oldest songs, extending them and sustaining them, is a part then of what Gary Snyder has called the real work of modern man: to uncover the inner structure and actual boundaries of the mind (Earth House Hold, 127).

What then of the interviews and talks collected here in the context of Snyders poetry? A lot of what follows is simply good, plain talk with a man who has a lively and very subtle mind and a wide range of experience and knowledge. But there is one important aspect of these texts that Id like to follow out for a moment: the place of the interview in our literature.

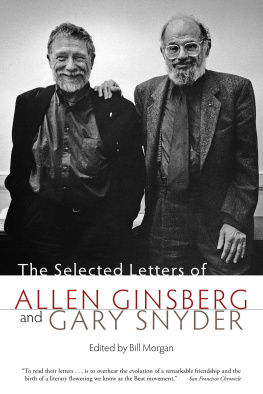

Scholars today take for granted the journals, workbooks and letters of authors as important source materials. And though primarily personal, these different kinds of writing have led in significant directions beyond their original bounds. Some have become recognized separate genres; such was the case with Bashs travel diaries. Letters have provided possibilities for greatly expanding the scope of the novel in the European context. It was the introduction of the epistolary element in eighteenth-century English and German works that brought attention to the individuals inner life, a quality we now perceive to be a central element of the novel. And more recently the journal has had an increasingly important place in the work of many poets, Paul Blackburn and Allen Ginsberg among them.