DISTANT NEIGHBORS

Copyright Chad Wriglesworth 2014

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN 978-1-61902-373-4

Interior design by VJB/Scribe

COUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

Dear Gary,

I think it would be both surprising and disappointing if we agreed more than we do. If we agreed about everything, what would we have to say to each other? Im for conversation.

Wendell Berry

Dear Wendell,

... Im not sure if anything is [between you and me] except distance and differing plant communities and climates. Thats how it feels to me, anyhow.

Gary Snyder

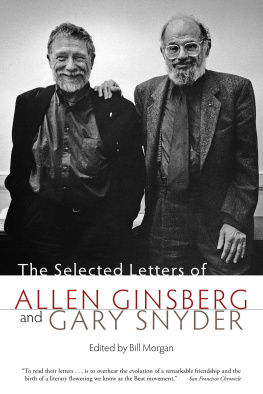

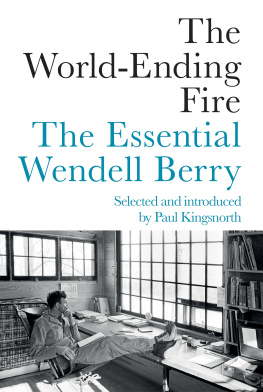

In contemporary American literature and environmental thought, Wendell Berry and Gary Snyder are often mentioned among the most important writers and public intellectuals of our day. Gary Snyder was born in 1930 and grew up on the West Coast in a politically active household of timber workers and dairy farmers during the 1930s and 40s. He studied literature and anthropology at Reed College and emerged in San Francisco as a central figure in the counterculture movement. He went on to travel throughout Japan and across the globe, before settling down in 1970 with his young family at Kitkitdizze, a homestead built with friends in the Sierra Nevada foothills. While living there, Snyder has written more than twenty works of prose and poetry that explore connections among ecology, Eastern philosophy, and indigenous anthropology. On the opposite side of the nation, Wendell Berry was born in 1934 and also grew up in a family committed to economic reform through the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative, a regional initiative begun in the 1920s to secure marketplace parity for local farmers, and established finally under the New Deal in 1941. After studying English at the University of Kentucky, Berry attended the Stanford Creative Writing Program in the late 1950s. His first novel, Nathan Coulter, was published in 1960. In 1965, after an extended period of travel, Berry moved with his family to Port Royal, Kentucky, where he has written more than fifty works of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. He continues to live and work alongside his wife, Tanya Berry, at Lanes Landing Farm.

For the past two years, I have had the pleasure of working with nearly 250 letters exchanged between Wendell Berry and Gary Snyder from the early 1970s to the present. When these two men began writing to each other, neither could have imagined the impact their lives would have on American literary and political culture, nor how their lives would link them to distinct places, as well as to one another. The letters tell a story of friendship between men committed to restoring ecological, cultural, and economic health in two different American regions. They speak of shared experiences at their respective homesteads Lanes Landing Farm and Kitkitdizze their influence on each others numerous writing projects, and their participation in groups such as the Lindisfarne Association, The Land Institute, and the Schumacher Society. But even more important, the letters exchanged between Berry and Snyder provide a lived example of something increasingly scarce in American culture two people working to recover and maintain the art of dialogue namely, the practice of sustaining a meaningful conversation that is both critical and hospitable, particularly when ideological tensions run high enough to spark division.

When reading the works of Wendell Berry and Gary Snyder, it can be tempting to stress points of difference, setting Snyders radical countercultural commitment to reinhabiting the Sierra Nevada foothills as a Zen Buddhist against Berrys agrarian practice of land stewardship that is shaped by Christian thought. However, focusing on differences alone clouds the unifying power of fidelity. The beauty and witness of this complex friendship exists in the mens expressions of particularity more than stark points of division. Snyder remains a practicing Zen Buddhist committed to principles of animism and hunting-and-gathering in the Sierra Nevada foothills, even as Berry works from Port Royal, equally dedicated to revising rural economies in relation to the inheritance of Western culture. Neither man practices a superficial what Berry calls feckless expression of religiosity, but instead weaves the ecological rhythms and patterns of the places they inhabit into their lives. Their distinct cultural upbringings, educations, and commitments to particular regions shape where they stand and how they write. Yet the shared practice of restoring the health of wounded places remains intact in the work of both men.

When differences arise between Wendell Berry and Gary Snyder, the two writers remain in conversation, benefiting from what Berry calls binocular vision, the art of gaining clarification of thought by perceiving through the other persons way of being. This leads to an awareness of their mutual existence in an expansive and generous source of energy that Snyder calls mind. For example, in 1980, after reading Snyders The Real Work: Interviews & Talks, 19641979, Berry sent a letter acknowledging key differences between himself and Snyder, yet was also moved to write the following:

... I read this book with a delight and gratitude that I rarely feel for the work of a contemporary. Given our obvious differences of geographic origin, experience, etc., it is uncanny how much I feel myself spoken for by this book and, when not spoken for, spoken to, instructed. It is a feeling I have only got elsewhere from hearing my brother speak in environmental controversies the realization and joyful relief of hearing someone speak well out of deeply held beliefs that I share. And this always involves a pleasant quieting of my own often too insistent impulse to speak.

In that same collection of interviews, Snyder in spite of any differences also spoke of the common bond he shared with Berry. While stating the importance of Eastern philosophy in his life and In this spirit, Berry and Snyder retain their particular ways of being, but through hospitable acts of perceiving beyond the self are also enlarged into a common existence of work and hope.

Wendell Berry and Gary Snyder knew about each other long before they met in the early 1970s. After Berry and Tanya Amyx were married in 1957, the couple spent a summer living in the Camp, a family cabin on the Kentucky River. That fall, they moved to nearby Georgetown, where Berry taught English at Georgetown College. Following the birth of their first child, Mary, the growing family headed west to California, where Berry attended the Stanford Creative Writing Program on a Wallace Stegner Fellowship (195860). It was then, while living in Mill Valley at what is now the OHanlon Center for the Arts, that Berry was reading Poetry magazine and took interest in the work of Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov, and Gary Snyder. Before long, he went to City Lights Books and bought a copy of Riprap (1959), Snyders first book of poems that was published in Kyoto, Japan, by Origin Press. The poems made a substantial impression on Berry, who, a few years later, spoke of Snyders work in A Secular Pilgrimage, a lecture given through United Campus Ministry at University of Kentucky, before it was published in

Next page