Translated from the Hebrew by Nicholas de Lange

in collaboration with the author

A Harvest Book Harcourt, Inc.

O RLANDO A USTIN N EW Y ORK S AN D IEGO T ORONTO L ONDON

Copyright 1968 by Am Oved Publishers Ltd.

English translation copyright 1972 by Chatto & Windus Ltd.

and Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should

be mailed to the following address: Permissions Department,

Harcourt, Inc., 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

www.HarcourtBooks.com

This is a translation of Mikha'el Sheli, originally published

in Israel by Am Oved Publishers Ltd. 1968

First published in English by Chatto & Windus Ltd.

and Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1972

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

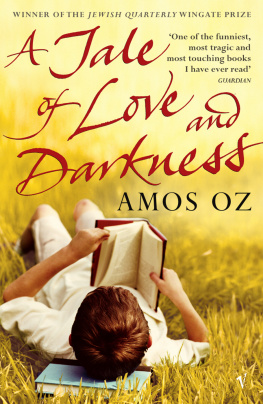

Oz, Amos.

My Michael/Amos Oz; translated from the Hebrew by Nicholas de Lange

in collaboration with the author.

[Mikha'el sheli. English]

p. cm.1st Harvest edition.

(A Harvest Book.)

Originally published: London: Chatto & Windus, 1972.

I. De Lange, N. R. M. (Nicholas Robert Michael), 1944. II. Title.

PJ5054.O9M513 2005

892.4'36dc22 2005040354

ISBN-13: 978-0156-03160-8 ISBN-10: 0-15-603160-4

Text set in Minion

Designed by Cathy Riggs

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvest edition 2005

A C E G I K J H F D B

Translator's Note

The translator's task is not simply impossible, it is also extremely difficult, and especially so in a book, such as My Michael, whose essence consists, to a large extent, in the texture of the language. A further complication is that Israeli Hebrew naturally reflects the varied linguistic backgrounds of the people who speak it, and the reader may amuse himself by spotting among the characters in this book examples of almost all the national and linguistic groups who go to make up the population of Israel. Among the older generation Polish and Yiddish predominate; Hannah's mother speaks both these but is more at home in Russian and speaks Hebrew with difficulty; then there are Germans, Arabs, Persians, Yemenites, and even Bokharians. Each of the characters, including native Hebrew-speakers like Michael and Hannah and their contemporaries, speaks his own distinctive brand of Hebrew; I have done my best to convey this variety in the translation, but I should like to draw attention to it here because it is an integral feature of the book, which might confuse or elude a reader who has never experienced it.

The Israeli background is unfamiliar, but not, I hope, unintelligible. The calendar is, of course, the Jewish calendar, dominated by the Sabbath, which begins and ends at sunset. As for the urban landscape of Jerusalem, which is so prominent in the story, and the interplay of the various factions of the population, Jews and Arabs, Europeans and Orientals, religious and "enlightened" Jews, I cannot hope to add anything to Hannah's own vivid and penetrating commentary.

A few specific points which may be helpful or interesting: It was pointed out by Israeli critics that Michael's surname, Gonen, means "protector," and it is only fair to offer this information, for what it is worth, to the English reader. I have kept several non-Hebrew words and phrases in their original languages; where they are not self-explanatory I have occasionally inserted the translation. ("Cholera," on p. 227, is not a diagnosis, but a common Polish curse.) One or two of the names have affectionate diminutive forms"Hannah," for example, becomes "Hannele" (in Yiddish) or "Hanka" (in Russian). The Palmach was the striking-force of the Haganah, the Jewish defense organization set up in Palestine during the British Mandate. In transliterating the Hebrew and Arabic names I have aimed at a certain consistency, basing myself on the current pronunciation, but I have sometimes surrendered to the claims of familiar usage. Ch, kh, and frequently h are to be pronounced like the ch in loch.

Finally, although I have enjoyed and benefited from the close collaboration of the author, any shortcomings in the translation are mine, not his, and I take full responsibility for them.

N. de L.

Cambridge

November 1971

1

I AM WRITING this because people I loved have died. I am writing this because when I was young I was full of the power of loving, and now that power of loving is dying. I do not want to die.

I am thirty years of age and a married woman. My husband is Dr. Michael Gonen, a geologist, a good-natured man. I loved him. We met in Terra Sancta College ten years ago. I was a first-year student at the Hebrew University, in the days when lectures were still given in Terra Sancta College.

This is how we met:

One winter's day at nine o'clock in the morning I slipped coming downstairs. A young stranger caught me by the elbow. His hand was strong and full of restraint. I saw short fingers with flat nails. Pale fingers with soft black down on the knuckles. He hurried to stop me falling, and I leaned on his arm until the pain passed. I felt at a loss, because it is disconcerting to slip suddenly in front of strangers: searching, inquisitive eyes and malicious smiles. And I was embarrassed because the young stranger's hand was broad and warm. As he held me I could feel the warmth of his fingers through the sleeve of the blue woolen dress my mother had knitted me. It was winter in Jerusalem.

He asked me whether I had hurt myself.

I said I thought I had twisted my ankle.

He said he had always liked the word "ankle." He smiled. His smile was embarrassed and embarrassing. I blushed. Nor did I refuse when he asked if he could take me to the cafeteria on the ground floor. My leg hurt. Terra Sancta College is a Christian convent which was loaned to the Hebrew University after the 1948 war when the buildings on Mount Scopus were cut off. It is a cold building; the corridors are tall and wide. I felt distracted as I followed this young stranger who was holding on to me. I was happy to respond to his voice. I was unable to look straight at him and examine his face. I sensed, rather than saw, that his face was long and lean and dark.

"Now let's sit down," he said.

We sat down, neither of us looking at the other. Without asking what I wanted he ordered two cups of coffee. I loved my late father more than any other man in the world. When my new acquaintance turned his head I saw that his hair was cropped short and that he was unevenly shaven. Dark bristles showed, especially under his chin. I do not know why this detail struck me as important, in fact as a point in his favor. I liked his smile and his fingers, which were playing with a teaspoon as if they had an independent life of their own. And the spoon enjoyed being held by them. My own finger felt a faint urge to touch his chin, on the spot where he had not shaved properly and where the bristles sprouted.

Michael Gonen was his name.

He was a third-year geology student. He had been born and brought up in Holon. "It's cold in this Jerusalem of yours."

"My Jerusalem? How do you know I'm from Jerusalem?"

He was sorry, he said, if he was wrong for once, but he did not think he was wrong. He had learned by now to spot a Jerusalemite at first sight. As he spoke he looked into my eyes for the first time. His eyes were gray. I noticed a flicker of amusement in them, but not a cheerful flicker. I told him that his guess was right. I was indeed a Jerusalemite.

Next page