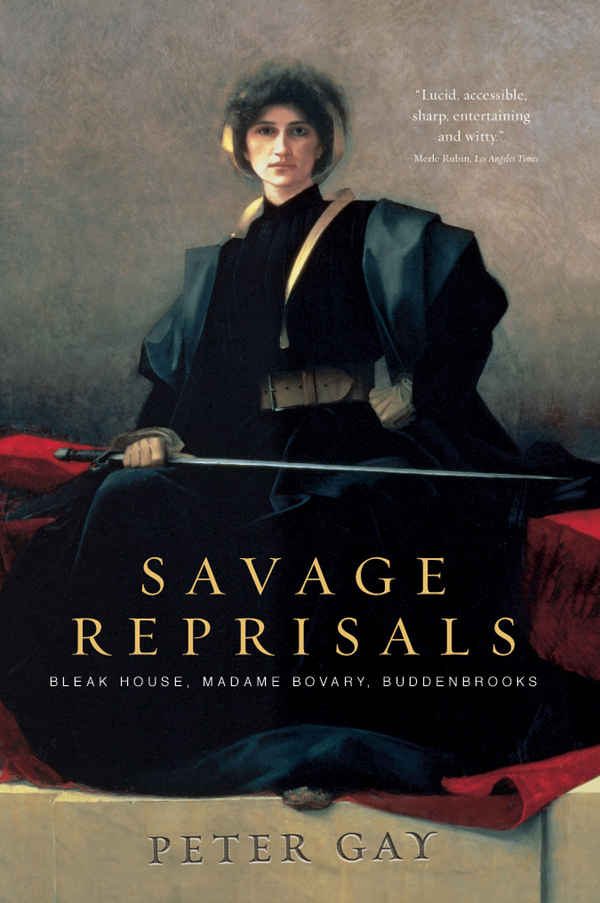

SAVAGE REPRISALS

Bleak House

Madame Bovary

Budden brooks

PETER GAY

To Dorothy and Lewis Cullman,

who changed my life,

and to

Doron and Jo Ben-Atar

Jerry and Bella Berson

Henry and Jane Turner,

my New Haven crew

The face of Dickens... is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry, in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.

George Orwell on Charles Dickens (1939)

For Flaubert, who all his life repeatedly declared that he wrote to take his vengeance on reality, it was above all negative experiences that inspired literary creation.

Mario Vargas Llosa on Gustave Flaubert (1975)

But the only weapon available to the artists sensitivity, to let him react with it to phenomena and experiences, to defend himself against them handsomely, is expression, is description. And this reaction by expression which (to speak with a certain psychological radicalism) is the artists sublime revenge on his experience, will be all the more vehement the more refined his sensitivity.

Thomas Mann on Thomas Mann (1906)

CONTENTS

, by Alfred Pierre Agache (18431915). Oil on canvas, Art Gallery of Toronto, Canada, 1896.

Original caption: Author Charles Dickens surrounded by his characters. From a drawing by J.R. Brown. Undated illustration. Corbis.

, by Albert August Fourie. Muse des Beaux-Arts, Rouen. Photo credit: Giraudon/ Art Resource NY.

by Thomas Mann, 1901. Courtesy of S. Fischer Verlag.

DURING THE SPECTACULAR CAREER OF LITERARY Realism in the nineteenth century, the style was covered with accolades, none more heartfelt than Walt Whitmans: For facts properly told, how mean appear all romances. Honor de Balzac famously saw himself as the amanuensis of history, a vaulting claim that the following pages will serve to examine and complicate, but which on their own convey a novelists powerful sense of reality. And in February 1863, Ivan Turgenev brought word to fellow diners in Paris, all of them prominent literary figuresFlaubert was there, as were Frances leading critic, Sainte-Beuve, and the Goncourt brothers, diarists and noveliststhat Russian writers, too, a little belatedly, had joined the Realist party.

In fact, it is fair to say that well into the twentieth century, novelists across Europe and the United States were firmly committed to the Reality Principle. They made, as it were, a tacit compact with their reading public that obligated them to remain close to truths about individuals and their society, to invent only real people and situations, in short to be trustworthy in their fictions about ordinary life. Romantic sagas about gallant knights and improbable adventures, seductive ladies and doomed lovers, all bathed in extravagant luxury, were not for them. Rather, the Realists found their materials in circumstances essentially like their bourgeois readers own styles of speech and ways of life. Even classic modernists like Marcel Proust or James Joyce created characters that, they insisted, obeyed the laws of human nature; in fact, A la recherche du temps perdu and Ulysses aimed at penetrating to the heart of internal life, the one with meticulous analyses and the other with linguistic experiments, more effectively than their more predictable fellow novelists could manage. Avant-garde or conventional, Realists made exceptional efforts to paint credible backgrounds and credible personages.

The three writers I am exploring in this book were all Realists, each in his own way. Their writings consistently paid homage to their commitment to the mundane. For all the eccentrics that populate Charles Dickenss novels, all his unsubtle division of characters into heroes and villains, he insisted in the strongest termsin Bleak House perhaps most urgentlythat he was in league with nature and science in imagining the scenes he spread out before his readers. Thomas Mann rifled his memories of Lbeck and canvassed his older brother Heinrich, other family members, and older acquaintances to provide his Buddenbrooks with the authority of living verisimilitude. Even Gustave Flaubert, who despised the newly fashionable genre called Realism for what he derided as its alleged vagueness and vulgarity, developed his own brand of Realism with fussy, downright obsessive care, making the characters in Madame Bovary as lifelike as possible. Whatever precise meaning authors, critics, and readers might assign to Realism, they could agree that the serious novelist must strictly confine himselfand herselfto plausible characters living in plausible surroundings and participating in plausible (and one hoped, interesting) events.

But their increasingly prestigious vocation as novelists pushed leading Realists beyond the Reality Principle. They were makers of literature, not mere photographers or stenographers of commonplace life. Their prized imaginative powers liberated them in ways barred to scientists of societysociologists, political scientists, anthropologists, historiansfor whom facts and their rational interpretation remained paramount. That is why nineteenth-century writers basked in the right to cherish their freedom from pedestrian constraintsof course always within reason. In the extraordinary letters that Flaubert wrote to his mistress Louise Colet at midcentury while he was at work on Madame Bovary , long bulletins from the front that amount to a treatise in aesthetics, he exclaimed over and over: That is everything: the love of Art.

For his part Thomas Mann, astonished that Buddenbrooks should have caused a sensation in Lbeck and bad blood, protested against this literal-minded reception of his first novel at home. The reality that a writer subjects to his intentions, he wrote with some indignation of his own, may be his daily world, may as a character be his closest and most beloved; he may show himself as subordinate as possible to details provided by reality, may use its deepest trait greedily and obediently for his text; and yet there will remain for himand should for all the world!an immeasurable difference between the reality and his handiwork: that is to say, the essential difference which forever separates the world of reality from that of art.

This Realist manifesto is too eloquent to require much comment. There is no point in making excessive demands on the realism of Realism. Certainly, as Realist novelists and their readers knew perfectly well, Realism is not reality. At one point in Buddenbrooks , Mann propels the tale forward with the bridge passage, Two and a half years later, a reminder that in fiction time makes acrobatic leaps. Again, late in Education sentimentale, Flaubert breaks into the continuity of his heros life with a famous two-word paragraph, He traveled, and then in a few terse words reports what happened to Frdric Moreau between 1848 and 1867. The Realist novel cuts the world apart and puts it together again in distinctive ways. Its reality is stylizedpushed and twistedto serve the requirements of an authors plots and character developments. Even when novelists deliberately resort to such easy, lazy tricks as the long arm of coincidence and the all-solving deus ex machina, they profess that the world they are constructing is authentic.

Next page