Seeing What

Others Dont

Seeing What

Others Dont

THE REMARKABLE WAYS

WE GAIN INSIGHTS

GARY KLEIN

PublicAffairs

New York

Copyright 2013 by Gary Klein.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs,

a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book Design by Pauline Brown

Typeset in Bembo Std by the Perseus Books Group

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Klein, Gary A.

Seeing what others dont : the remarkable ways we gain insights / Gary Klein. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61039-275-4 (e-book)

1. Insight. I. Title.

BF449.5.K58 2013

153.4dc23

2013005824

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jacob and Ruth

CONTENTS

ENTERING THROUGH

THE GATES OF INSIGHT

T HIS WASNT SUPPOSED TO BE A MYSTERY STORY. It started out innocently as a collection of clippings from newspapers and magazines. I would come across an article describing how someone made an unusual discovery, and Id add it to a stack on my desk. The stack included notes describing stories Id heard during interviews or in conversations. Like other enthusiasms, the stack sometimes got covered up in the competition for space. But unlike the rest, this stack survived. Whenever it got completely buried, it recovered each time I found another article and searched for a place to put it. This pile of clippings endured the occasional bursts of house cleaning that sent many of its neighbors into the purgatory of my file cabinets, if not the trash basket. Im not sure why it survived. I didnt have any grand plans for it. I just liked adding new material to it. And I liked sifting through it every few months, savoring the stories.

Heres an example of the type of incident that made its way into my stack. Two cops were stuck in traffic, but they didnt feel impatient. They were on a routine patrol, and not much was going on that morning. The older cop was driving. Hes the one who told me the story, proud of his partner. As they waited for the light to change, the younger cop glanced at the fancy new BMW in front of them. The driver took a long drag on his cigarette, took it out of his mouth, and flicked the ashes onto the upholstery.

Did you see that? He just ashed his car, the younger cop exclaimed. He couldnt believe it. Thats a new car and he just ashed his cigarette in that car. That was his insight. Who would ash his cigarette in a brand new car? Not the owner of the car. Not a friend who borrowed the car. Possibly a guy who had just stolen the car. As the older cop described it, We lit him up. Wham! Were in pursuit, stolen car. Beautiful observation. Genius. I wanted to hug him it was so smart.

I like this kind of story that shows people being clever, noticing things that arent obvious to others. Theyre a refreshing antidote to all the depressing tales in the popular press about how irrational and biased we can be. It feels good to document times when people like the young police officer make astute observations.

What changed the fate of this stack of discoveries was that I couldnt answer an important question. I am a cognitive psychologist and have spent my career observing the way people make decisions. Different types of groups invite me to give talks about my work. In 2005, I learned about a movement called positive psychology, which was started by Martin Seligman, a psychotherapist who concluded that his profession was out of balance. Therapists tried to make disturbed and tormented people less miserable. However, eliminating their misery just left them at zero. What about the positive side of their experience? Seligman was looking for ways to add meaning and pleasure to the lives of his clients.

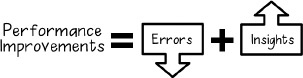

I felt that the concept of positive psychology applied to decision making as well. Decision researchers were trying to reduce errors, which is important, but we also needed to help people gain expertise and make insightful decisions. Starting in 2005, I added a slide to my presentations showing two arrows to illustrate what I meant. Here is an updated version of that slide:

To improve performance, we need to do two things. The down arrow is what we have to reduce, errors. The up arrow is what we have to increase, insights. Performance improvement depends on doing both of these things.

We tend to look for ways to eliminate errors. Thats the down arrow. But if we eliminate all errors we havent created any insights. Eliminating errors wont help us catch a car thief who chooses the wrong moment to flick his ashes.

Ideally, reducing mistakes would at least help us gain insights but I dont believe thats how it works. I suspect the relation between the arrows runs the other way. When we put too much energy into eliminating mistakes, were less likely to gain insights. Having insights is a different matter from preventing mistakes.

When I showed this slide in my seminars, I got a lot of head nods. The participants agreed that their organizations were all about the down arrow. They felt frustrated by organizations that stifled their attempts to do a good job. Their organizations hammered home the message of reducing mistakes, perhaps because it is easier for managers to cut down on mistakes than to encourage insights. Mistakes are visible, costly, and embarrassing.

However, I also started getting a question: How can we boost the up arrow? The audiences wanted to know how they could increase insights. And that was the question I couldnt answer. How to boost insights? I had to admit that I didnt know anything about insights. This admission usually drew a sympathetic laugh. It also drew requests to come back if I ever learned anything useful about insights.

After one such seminar in Singapore, I had a long flight back to the United States to reflect on the up arrow. I wished I could help all the people who wanted to restore a balance between the two arrows in the equation. And then I remembered my stack of clippings that was waiting for me back home.

So in September 2009, I started my own investigation of insight. I began collecting more examples. I was just poking around, nothing serious. I wanted to explore how people come up with unexpected insights in their daily work. Most studies on insight take place in laboratory settings using college undergraduates trying to solve artificial puzzles. I wondered if I could learn anything useful by studying the way people form insights in natural settings.