Eternitys Sunrise

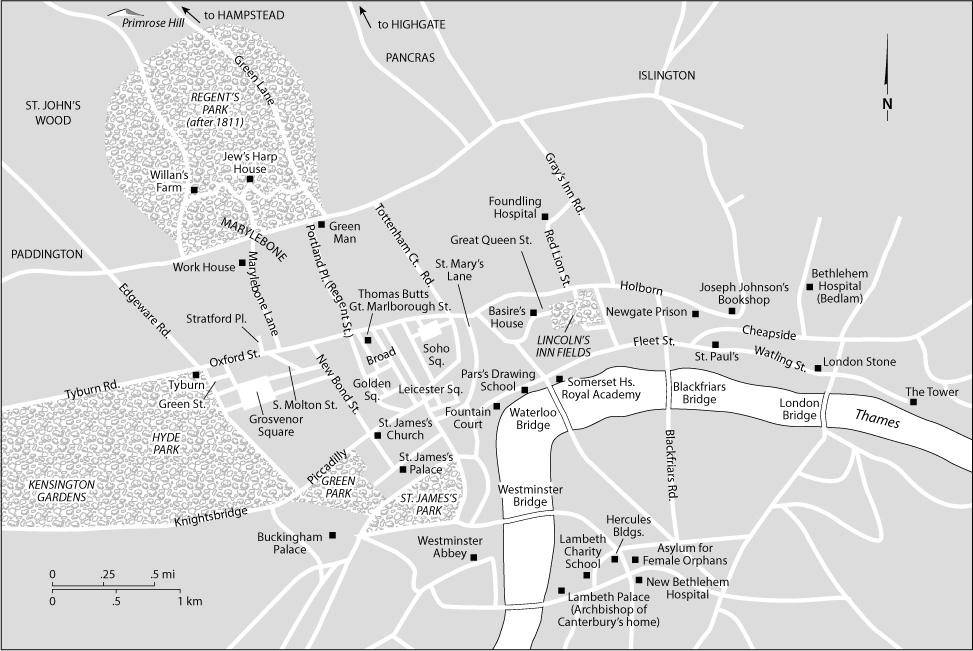

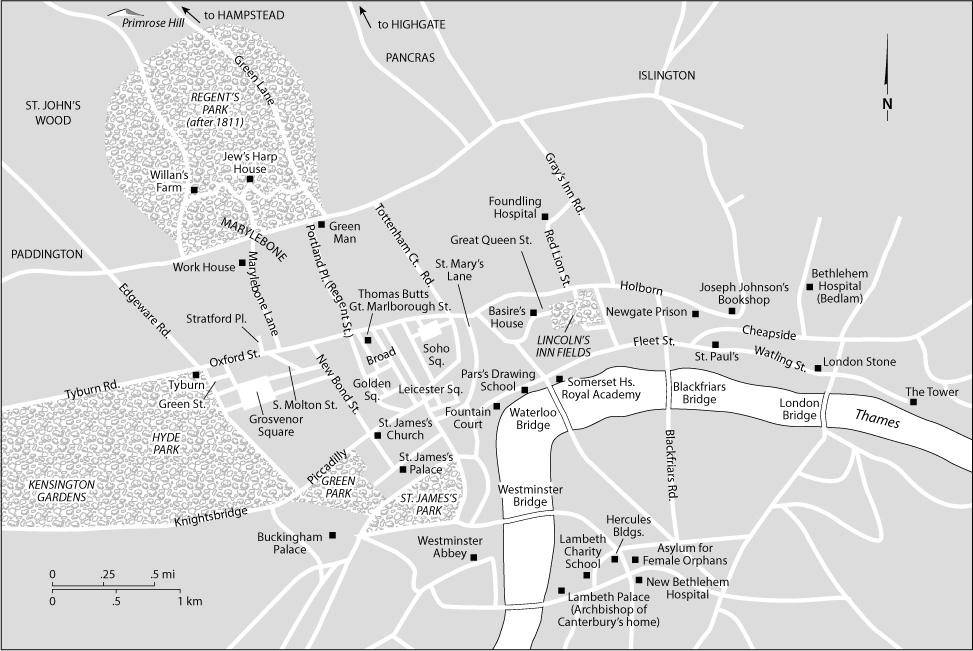

William Blakes London

ETERNITYS SUNRISE

The Imaginative World of William Blake

Leo Damrosch

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund and the Louis Stern Memorial Fund. The acquisition of images was supported in part by a grant from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Copyright 2015 by Leo Damrosch.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (UK office).

The Poems of Our Climate from THE COLLECTED POEMS OF WALLACE STEVENS by Wallace Stevens, copyright 1954 by Wallace Stevens and copyright renewed 1982 by Holly Stevens. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Designed by James J. Johnson.

Set in Dante type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015942776

ISBN 978-0-300-20067-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To

Harold Bloom and E. D. Hirsch

and in memory of

Charles Ryskamp

three great teachers who first inspired my love of Blake

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to express my gratitude to my agent, Tina Bennett, for her unfailing loyalty over many years; to Jennifer Banks, my marvelously encouraging and intuitive editor; to Laura Jones Dooley, who ably guided the manuscript through all the stages of production; and above all to my wife, Joyce Van Dyke, whose imaginative yet rigorous critique of successive drafts improved this book immeasurably.

Eternitys Sunrise

INTRODUCTION

WILLIAM BLAKE was a creative genius, one of the most original artists and poets who ever lived. Some of his works are widely known: the image of a majestic creator tracing the orb of the sun with a pair of compasses; the hypnotically powerful lyric Tyger tyger burning bright; the poem known as Jerusalem that was later set to music and became a popular hymn. But many years had to pass after Blakes death before he had any reputation at all. His poems were virtually unknown in his lifetime, and even as a visual artist he was considered a minor figure, known mainly for engraving designsusually by other artiststo illustrate books. These jobs dwindled as the years went by, and his contemporaries would have been incredulous if they could have known that one day he would be recognized as a major figure in not just one art but two, and that the greatest museums and libraries would treasure works that he sold for absurdly low prices when he could sell them at all. The disappointments of Blakes worldly career illustrate Schopenhauers saying that talent hits a target no one else can hit, while genius hits a target no one else can see.

Blake was not only a superb painter and poet, one of the very few equally distinguished in both arts, but a profound thinker as well. Trenchantly critical of received values, he was a counterculture prophet whose art still challenges us to think afresh about almost every aspect of experiencesocial, political, philosophical, religious, erotic, and aesthetic. As he developed his ideas, he evolved a complex personal mythology that incorporated elements of Christian belief and drew upon

It is important to recognize that Blake was a troubled spirit, subject to deep psychic stresses, with what we would now call paranoid and schizoid tendencies that were sometimes overwhelming. During his life he was often accused of madness, but the artist Samuel Palmer, who knew him well, remembered him as one of the sanest, if not the most thoroughly sane man I have ever known. And a Baptist minister replied, when asked if he thought Blake was cracked, Yes, but his is a crack that lets in the light.

Throughout his life Blake was bitterly aware that he was an outsider, not just with respect to society as a whole, but even in his chosen profession of graphic art. It was from a wounding sense of alienation and dividedness that his great myth emerged, in response to what Algernon Charles Swinburne called the incredible fever of spirit, under the sting and stress of which he thought and labored all his life through. In some sense we are all outsiders, and his imaginative words and pictures speak to us with undiminished power.

Although Blake is never pious or doctrinal, his thinking is religious in the sense that it addresses the fundamental dilemmas of human existenceour place in the universe, our dread of mortality, our yearning for some ultimate source of meaning. His goal, he said, was to rouse the faculties to act, and he hoped that we would use his images and symbols to provoke a spiritual breakthrough. If the spectator could enter into these images in his imagination, approaching them on the fiery chariot of his contemplative thought; if he could enter into Noahs rainbow or into his bosom, or could make a friend and companion of one of these images of wonder which always entreats him to leave mortal things, as he must know; then would he arise from his grave, then would he meet the Lord in the air, and then he would be happy.make us happy. But it is a poignant fact that Blakes most powerful writing, as the years went by, was haunted by intractable barriers to happiness.

A little poem that Blake never published, entitled Eternity, condenses an important part of his message into four eloquent lines:

He who binds to himself a joy

Does the wingd life destroy,

But he who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in Eternitys sunrise.

Blake believed that we live in the midst of Eternity right here and now and that if we could open our consciousness to the fullness of being, it would be like experiencing a sunrise that never ends. That would not be a mystical escape from realityhe was never a mystic in that sensebut a fuller and deeper engagement with reality. Yet he also knew how hard it is to relinquish the self-centered possessiveness that kills joy instead of kissing it, and much of his work focuses on that struggle.

This book has a strongly biographical focus, but it is not a systematic biography. Two excellent ones already exist, by Peter Ackroyd and G. E. Bentley, each with its own strengths, and in any case Blakes life was relatively uneventful.

Next page