Adventurer

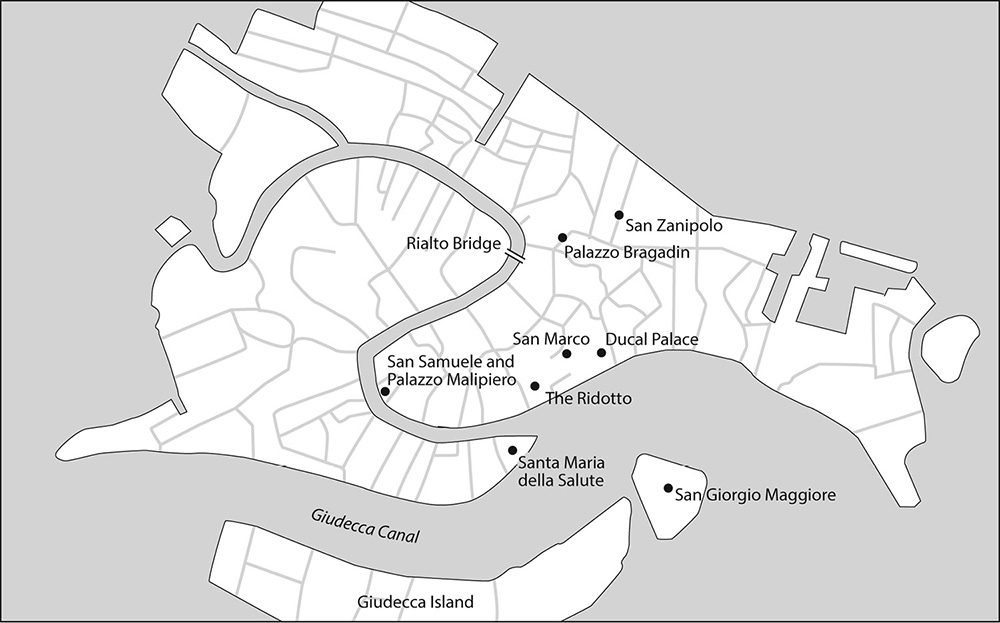

Casanovas Venice

Adventurer

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF GIACOMO CASANOVA

Leo Damrosch

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund

and the Louis Stern Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2022 by Leo Damrosch. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Adobe Garamond type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021949604

ISBN 978-0-300-24828-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Acknowledgments

I owe special thanks to three people above all. Tina Bennett became my agent twenty years ago when I had never published anything for general readers; with each of the six books that ensued she has inspired and encouraged me, and sustained me with her rock-solid support. Jennifer Banks, my editor at Yale University Press, for this and three previous books, has an ideal combination of intelligence, imagination, and wisdom, helping each of them to find its best form, and afterward presiding over a superb production team. And my wife, Joyce Van Dyke, brings a fellow writers insight to everything I write. Her advice has been essential in developing each project, she has improved every page and every chapter with a keen critical eye, and her perspective as a playwright has been invaluable in creating narrative energy and flow.

Finally, this book is appearing at a cultural moment when the story of a notorious seducer needs to be addressed frankly and critically. For helping to conceptualize and ponder the issues involved, I am deeply grateful to these gifted advisers.

INTRODUCTION

The Challenge of Casanova

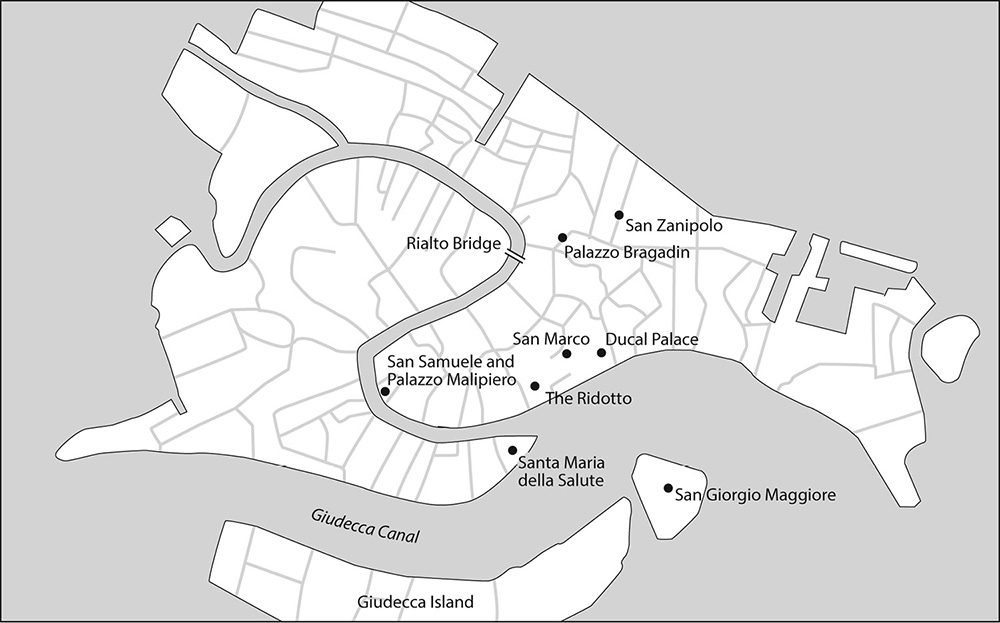

Everyone knows that Casanova was a seducer. He belongs to that rare company of mortals whose personal names have floated free from history, and we know what a Casanova is even if we know nothing about the man who bore that name. He was Giacomo Casanova, a gifted and complicated Venetian who lived from 1725 to 1798, and his story is a fascinating one. But although he was more than his myth, the myth is grounded in truth. His career as a seducer, already notorious in his own time, is often disturbing and sometimes very dark. It challenges any reader today, and still more it challenges a biographer. Casanova aspired to a life of freedom from restraintsbut freedom at whose expense?

There have been a number of biographies of Casanova, but the time is overdue for a biography of a different kind. He was the first to tell his own story, in a massive autobiography entitled Histoire de Ma Vie. Fluent in French, he wrote in that language since unlike Italian it was understood throughout Europe. The word histoire can mean story as well as history, and a story it certainly is. Previous biographers have tended to retell it as he told it, adopting his own point of view with only occasional queries. Some have betrayed a vicarious investment in his tales of seduction, just as many readers clearly have; its interesting that men with great political power, such as Winston Churchill and Franois Mitterrand, have been especially warm admirers of Casanova.

In fiction such a character might be a charming rogue, but in real life Casanovas

Proud of being a bad boy, Casanova was self-serving in every aspect of his life, not just the sexual, but the erotic encounters in the Histoire vary greatly. Sometimes his behavior was abusive in ways that are not just disturbing today, but would have seemed disturbing to many people in his own day. At other times he convincingly describes experiences of deep mutual enjoyment.

Casanova did value his partners individuality, and he genuinely wanted to share mutual pleasure with them. But the balance of power was always unequal, and every one of his relationships was short-livedsometimes only a single encounter, and never lasting more than a couple of months. Not until very late in life did he live with a woman for more than a brief time. And although he occasionally considered marriage, or claims he did, he made sure that it never happened.

With only two or three of his many partnersand he names over a hundredwas Casanova really what most people consider in love. What he calls love usually began with excited infatuation, and sometimes it developed into passion, but it always burned out fast. The psychoanalyst Lydia Flem claims, There is not a trace of misogyny in Casanova; in the great book of life, women are his masters. But if his technique of seduction sometimes gave women a feeling of power, that feeling never lasted.

To hear him tell it, desire was always mutual and relationships always ended amicably. But even in his own telling, its obvious that some women got involved with him against their better judgment, and were regretful or bitter afterward. Even if relationships did end amicably, what would that mean? Casanova saw it as evidence of his generosity of spirit, but it can also be seen as invincible narcissism. The critic Franois Roustang provides an insight that goes much deeper than Casanovas rationalizations: He is incapable of making the women he deceives suffernot so much for their sakes as for his own,

In reality, Casanovas treatment of women was manipulative. He had power over them, he knew it, and he enjoyed exploiting it. He hardly ever acknowledges the power imbalance between women and men, but once in an essay he does mention our despotism over women. That seems to mean the social and legal power over women that wethe male sextake for granted.

Women in the eighteenth century were subjected to social and legal constraints that Casanova never was. Some with whom he got involved were adventurers like himself, traveling opportunistically under assumed names and enjoying their independence. But most were in no position to move on freely, as he always did, after an affair came to an end. They were girls still living with their families, or wives who were willing to risk a brief holiday from marriage. Since respectable marriages were arranged by families for financial considerations, with little regard for the desires of the spouses, the numerous wives with whom Casanova slept may have found him romantically as well as erotically exciting. He says they did, and there is probably some truth to that. But when he moved on they couldnt, and didnt.

There were prostitutes, too, sometimes in upscale brothels, sometimes encountered casually. Like most men, Casanova didnt reflect about why they were reduced to supporting themselves in that way; he simply took their existence for granted. Many were orphans with no other means of survival, and some were girls whose impoverished parents had literally sold them into prostitution. He also had a number of encounters with girls whose parents, lacking other sources of income, were openly pimping them out, though he usually paid them with presents rather than cash.

Next page