Don King in the Twilight

Don King and I have had our differences over the years. And at times, they've been heated. I'm grateful that he allowed me to share the night of March 9, 2013, with him.

Don King arrived at Barclays Center for the March 9, 2013, IBF 175-pound title fight between Bernard Hopkins and Tavoris Cloud shortly after 8:00 PM.

King will be eighty-two years old on August 20, but he has the physical presence and vitality of a man half his age. His large bulky frame, Cheshire Cat grin, booming voice, and high-pitched laugh suggest a force of nature.

Wherever King goes, he's encapsulated in a bubble of public attention. Everyone, from high-ranking corporate executives to men and women on the street, stop and stare and are drawn to his side.

In the September 2, 1974, issue of Sports Illustrated, Mark Kram wrote, Don King is big, black, and hardly beautiful, a 50-carat setting of sparkling vulgarity and raw energy, a man who wants to swallow mountains, walk on oceans, and sleep on clouds.

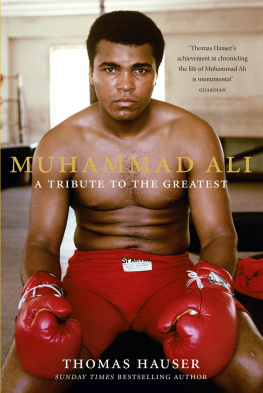

That was mainstream America's introduction to King. Two months later, Muhammad Ali dethroned George Foreman in Zaire with Don playing a key role in the promotion. In the decades that followed, King promoted more than five hundred world championship fights. At one point, Don King Productions could lay claim to promoting seven of the ten largest pay-per-view fights in history (as gauged by total buys) and twelve of the top twenty highest-grossing live boxing gates in the history of Nevada.

King has promoted Ali, Foreman, Joe Frazier, Larry Holmes, Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield, Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Julio Cesar Chavez, Felix Trinidad, Roy Jones, and dozens of other Hall of Fame fighters. He's one of the few people in boxing today who transcend the sport. His name and face are more recognizable than those of Floyd Mayweather Jr or any other active fighter.

People come up to me all the time, put their babies in my arms, and ask me to kiss them. King chortles. That doesn't happen to Bob Arum or Richard Schaefer.

Boxing fans are used to seeing King in a tuxedo on fight night; a shining apparition draped in bling that seems to reflect off everything from the top of his hair down to his black patent-leather shoes.

At Barclays Center, King had a different look. The promoter was wearing red-white-and-blue jogging shoes, maroon corduroy pants, a blue shirt, an American-flag-themed tie, and a rhinestone-studded blue-denim jacket accessorized by three Obama buttons. The jacket (one of three celebrating America that the promoter owns) was badly frayed. By contrast, King's fingernails were impeccably manicured. He had an unlit cigar in one hand and miniature flags representing two dozen nations in the other. The name of each country was written at the base of its respective flagstick.

There was a time when it didn't matter a whole lot to King who won or lost a big fight because he controlled both fighters. That time is long gone. Now it's rare for Don to control even one combatant in a major bout. Cloud was under contract to King, but the Hopkins fight was the last under their promotional agreement. It was also possible that this would be King's last fight on HBO.

What happened to King's power?

For starters, he was a prisoner of his own success. What had worked in the past stopped working as well as it had before. But King had enough money and enough trappings from the glory years that he wasn't forced to adapt. The times changed and he didn't change with them.

King is into control. He has always been hands-on in every area of his business. He likes everything to run through him and chooses not to share his tricks of the trade with anyone. Thus, he never had a strong number two to help with the heavy lifting or guide him in new directions.

Don had always played leverage to the hilt. For years, control of the heavyweight champion (Ali, Holmes, Tyson) and the heavyweights beneath them was his most valuable asset. Then he lost that control. He managed to thrive afterward with lighter-weight fighters like Felix Trinidad and Julio Cesar Chavez. But the power dynamic in boxing was shifting to favor the premium cable television networks. Network executivesfound other promoters easier to deal with than King. After Don took Mike Tyson to Showtime in the mid-1990s, HBO made a decision to license fewer fights from him. Then King lost Tyson, and Showtime moved away from him too. Eventually, King no longer had a fighter that network executives felt they absolutely needed, and HBO begin the process of helping to build Golden Boy as a countervailing promotional power.

Also, whatever corners King had cut as part of his business model (and there were many), other promoters began cutting with an even sharper razor. The world sanctioning organizations found new suitors to occupy the place on their balance sheets where King had once been. The tentacles of these promoters soon reached throughout the boxing industry as Don's once had.

Meanwhile, King's reputation was catching up with him. National attention focused on him in a critical way. Elite fighters became wary of signing with him. He was subjected to closer legal scrutiny than other promoters and, in some instances, held to a higher standard.

And finally, Don got old. People slow down at a certain age. There are no eighty-year-old international chess champions. At a certain age, men and women think one fewer move ahead than they used to.

I'm like Churchill, King says. I'll never surrender.

But one had the feeling at Barclays Center that King is nearing the end of an extraordinary journey. Indeed, although his fighter was the champion, it was Bernard Hopkins (promoted by Golden Boy) who had been listed first in pre-fight promotional material. Cloud was fungible, a guy with a belt. Hopkins vs. Cloud was about Hopkins.

The defining feature of Bernard's career has been his longevity. As noted by Tom Gerbasi, He took the time when boxers legacies get destroyed or at least tarnished and made his even greater.

Hopkins ascended to stardom with a twelfth-round knockout of Felix Trinidad on September 29, 2001. He was thirty-six years old, and the assumption was that his days in boxing were numbered.

Big number.

Over the next forty-one months, Bernard recorded victories over Carl Daniels, Morrade Hakkar, William Joppy, Robert Allen, Oscar De La Hoya, and Howard Eastman. Then, at age forty, he lost twice to Jermain Taylor. Now, surely, the end was near.

Hopkins's record has been uneven since then. Prior to facing Cloud, he hadn't scored a knockout since stopping De La Hoya in 2004. Over the previous eight years, he'd recorded 6 wins, 4 losses, and 1 draw with 1 no contest. He had won only one fight in the preceding thirty-five months. But he'd been competitive every time out. And what makes Bernard's ledger so impressive is his age. He's now forty-eight years old.

Margaret Goodman (former chief ringside physician for the Nevada State Athletic Commission) says, If a fighter is old enough to need Viagra, he shouldn't be boxing.

Hopkins says, I'm a fighter. This is what I do. Age is not my enemy. Don't look at the number. Look at the man. I'm not counting age. Everybody else is counting it. I'll stop when I want to stop.