As much a work of intellectual history as art history, Hausers work remains unparalleled in its scope as a study of the relations between the forces of social change and western art from its origins until the middle of the 20th century.

Harriss introductions to each volumedealing with Hausers aims, principles, concepts and terms are extremely useful. This edition should bring Hausers thought to the attention of a new generation of readers.

First published in 1951 Arnold Hausers commanding work presents an account of the development and meaning of art from its origins in the Stone Age through to the Film Age. Exploring the interaction between art and society, Hauser effectively details social and historical movements and sketches the frameworks within which visual art is produced.

This new edition provides an excellent introduction to the work of Arnold Hauser. In his general introduction to The SocialHistory of Art, Jonathan Harris assesses the importance of the work for contemporary art history and visual culture. In addition, an introduction to each volume provides a synopsis of Hausers narrative and serves as a critical guide to the text, identifying major themes, trends and arguments.

The Social History of Art

Arnold Hauser, with an introduction by Jonathan Harris

Volume IFrom Prehistoric Times to the Middle Ages

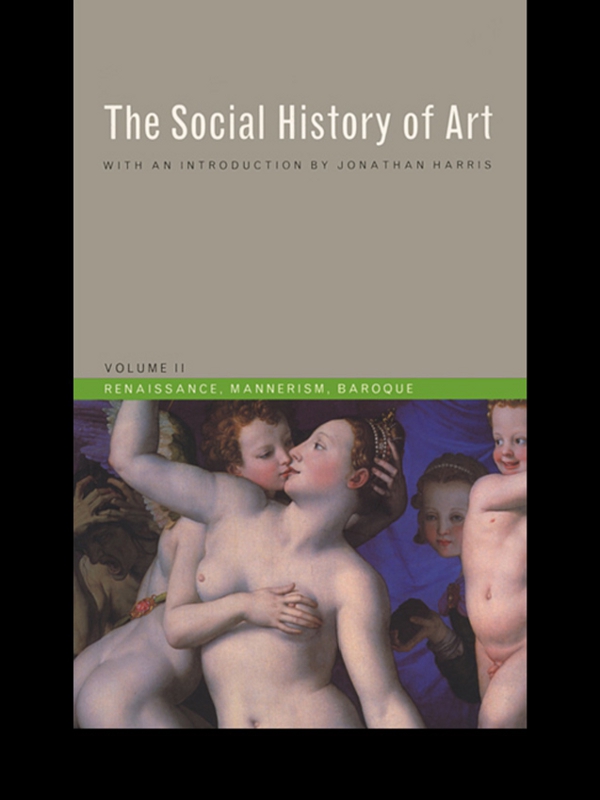

Volume IIRenaissance, Mannerism, Baroque

Volume IIIRococo, Classicism and Romanticism

Volume IVNaturalism, Impressionism, The Film Age

THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF ART

VOLUME II

Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque

Arnold Hauser

with an introduction by Jonathan Harris

First published in two volumes 1951

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

Second edition published in four volumes 1962

by Routledge & Kegan Paul plc

Third edition 1999

1951, 1962, 1999 The Estate of Arnold Hauser

Introductions 1999 Routledge

Translated in collaboration with the author by Stanley Godman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested

ISBN 0-203-98132-4 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-415-19946-8 (Vol. II)

ISBN 0-415-19945-X (Vol. I)

ISBN 0-415-19947-6 (Vol. III)

ISBN 0-415-19948-4 (Vol. IV)

ISBN 0-415-21386-X (Set)

ILLUSTRATIONS

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Jonathan Harris

Contexts of reception

Arnold Hausers The Social History of Art first appeared in 1951, published in two volumes by Routledge and Kegan Paul. The text is over 500,000 words in length and presents an account of the development and meaning of art from its origins in the Stone Age to the Film Age of Hausers own time. Since its publication, Hausers history has been reprinted often, testament to its continuing popularity around the world over nearly a half-century. From the early 1960s the study has been reprinted six times in a four-volume series, most recently in 1995. In the period since the Second World War the discipline of art history has grown and diversified remarkably, both in terms of the definition and extent of its chosen objects of study, and its range of operative theories and methods of description, analyses and evaluation. Hausers account, from one reading clear in its affiliation to Marxist principles of historical and social understandingthe centrality of class and class struggle, the social and cultural role of ideologies, and the determining influence of modes of economic production on artappeared at a moment when academic art history was still, in Britain at least, an lite and narrow concern, limited to a handful of university departments. Though Hausers intellectual background was thoroughly soaked in mid-European socio-cultural scholarship of a high order, only a relatively small portion of which was associated directly with Marxist or neo-Marxist perspectives, TheSocial History of Art arrived with the Cold War and its reputation quickly, and inevitably, suffered within the general backlash against political and intellectual Marxism which persisted within mainstream British and American society and culture until at least the 1960s and the birth of the so-called New Left. At this juncture, its first moment of reception, Hausers study, actually highly conventional in its definition and selection of artefacts deemed worthy of consideration, was liable to be attacked and even vilified because of its declared theoretical and political orientation.

By the mid-1980s, a later version of Marxism, disseminated primarily through the development of academic media and cultural studies programmes, often interwoven with feminist, structuralist and psychoanalytic themes and perspectives, had gained (and regained) an intellectual respectability in rough and ironic proportion to the loss of its political significance in western Europe and the USA since the 1930s. Hausers study was liable to be seen in this second moment of reception as an interesting, if, on the whole, crude, antecedent within the development of a disciplinary specialism identified with contemporary academic art and cultural historians and theorists such as Edward Said, Raymond Williams, Pierre Bourdieu and T.J.Clark. By the 1980s, however, Hausers orthodox choice of objects of study, along with his unquestioned reliance on the largely unexamined category of artseen by many adherents of cultural studies as inherently reactionarymeant that, once again, his history could be dismissed, this time primarily on the grounds of its both stated and tacit principles of selection. Yet The Social History of Art, whatever its uneven critical fortunes and continuing marginal place in most university courses, has remained an item, or an obstacle, to be reador at least dismissively referred towithin the study of the history of art. Why should this be the case?