for Julian and Luca

The units of currency in late medieval England were pounds (), shillings (s) and pence (d); there were twelve pence to the shilling and twenty shillings to the pound. Money could also be accounted in marks, each of which was equivalent to two-thirds of a pound (13s 4d). Among the coins in circulation were the groat, worth a third of a shilling (4d), and the noble, worth a third of a pound (6s 8d).

The spelling of all quotations from contemporary sources has been modernised . As far as possible, vocabulary has been left unaltered, but a few now-obsolete words have been substituted for ease of comprehension. Some less familiar words, and familiar words used in unfamiliar ways, are listed below.

advertise warn, notify, instruct (also advertisement, instruction)

assoil absolve, pardon

avoid remove

brothel good-for-nothing

but if unless

con know how to

conceive think, understand (also conceit, opinion or understanding)

crazed ill

devoir duty

divers several

fain glad, gladly

frieze coarse woollen cloth

fumous angry

hap (n.) happening; (v.) happen

harness armour

heavy sad or oppressive

journey either in modern sense, or a days work

labour (v.) try to achieve or seek to persuade

large liberal, ample: can have positive connotations of generosity or negative ones of offensiveness

let either allow or prevent

lewd ignorant or foolish or vulgar

liefer rather (from lief, glad or willing)

livelihood landed estates or the income from such property

lumish malicious

maintenance support of a litigant by someone with no legitimate connection to the case

marvellous to be marvelled at, not necessarily in a positive sense

move urge

noise (n.) rumour; (v.) to spread a rumour

noyous harmful

obloquy bad repute

paid pleased (as in well paid and evilpaid)

pipe roll

proper ones own

sad wise, sensible, serious

sans without

shrew malevolent person

shrewd malicious or dangerous or poor in quality

simple plain or humble or foolish

strange alien, other; or unfriendly

therefor for that object or purpose

treat (v.) negotiate

trow (v.) believe, think

unsitting unsuitable, unbecoming

very true

vouchsafe (v.) graciously agree

weal well-being

wicket small opening in a door or wall

worship qualities characteristic of gentility , or the respect in which someone displaying those qualities is held

wroth furious

I could not have been more fortunate in my agent, Patrick Walsh, and my editors, Jon Riley and Walter Donohue: they have made the impossible happen , several times over. To them, and to Charles Boyle, Ron Costley, Josine Meijer, and the remarkable team at Faber, I am extremely grateful.

Christine Carpenter introduced me to the Pastons sixteen years ago; for that, as for so much else, I am profoundly in her debt. As always, she has been unfailingly generous with her expertise and her friendship, as have Richard Partington, Caroline Burt, John Watts, Benjamin Thompson and Rosemary Horrox. Richard Beadle first made me think about telling the Pastons story, and Colin Richmond offered kind encouragement along the way. Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, has been a happy academic home for me for ten years, and I must thank everyone there master, fellows, staff and students, and particularly the historians for making it so.

I owe more than I can say to the people who have seen me through the writing of this book from its very beginnings: Rachel Aris, Lucyann Ashdown, Tony Badger, Gary Beggerow, Sarah Beglin, Nigel Blackwood, Katie Brown, Melissa Calaresu, Virginia Crompton, Russell Davies, John Foot, Robert Gordon, Harriet Hawkes, Grace Hodge, David Jarvis, Emily Lawson, Jo Marsh, Rosemary Parkinson, Barbara Placido, Anne Shewring, Keith Straughan, Catherine Taylor, Thalia Walters and Simon Whiteman. Without Allison Weild, the book could not have been written: thank you.

My family, and especially my sisters Harriet and Portia, have been a constant source of encouragement and inspiration. Very special thanks to my parents, Grahame and Gwyneth, for a truly extraordinary combination of emotional, practical and intellectual support.

Julian Ferraro has helped in more ways than I can begin to describe. The book is dedicated to him and to Luca, with all my love.

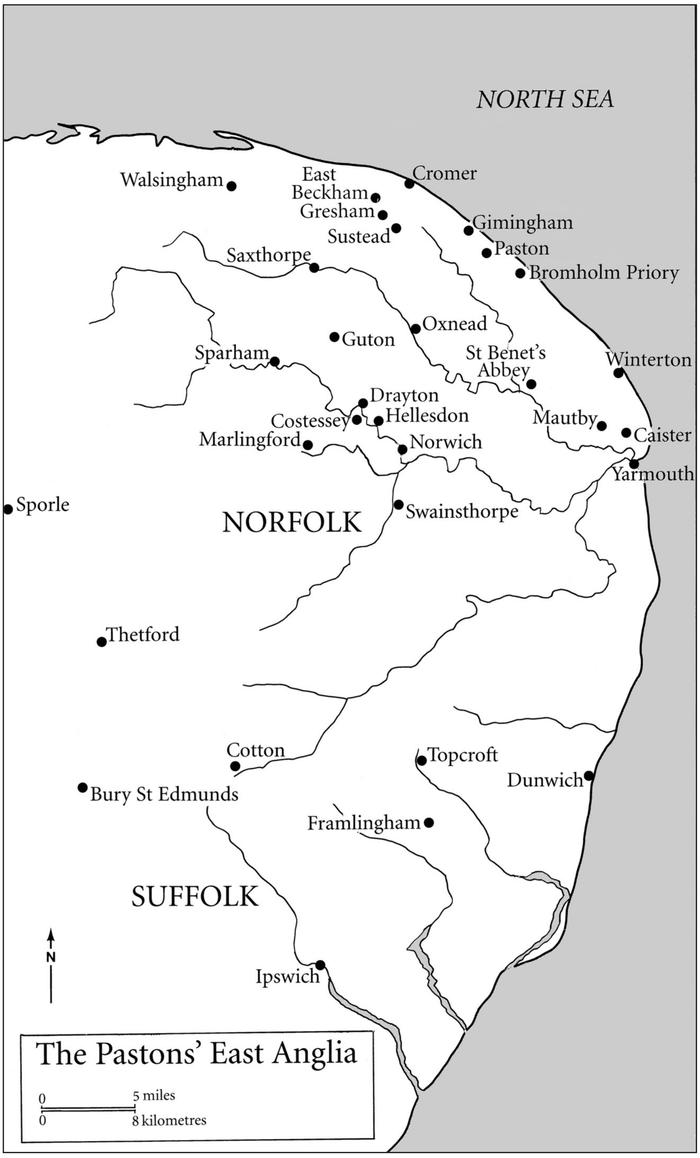

BLOOD & ROSES

In the late spring of 1735 the Reverend Francis Blomefield, a noted antiquarian and local historian, was summoned to give an expert opinion on the family papers of William Paston, the second Earl of Yarmouth, who had died a little over two years earlier. The Earl had been staving off bankruptcy by the narrowest of margins for the last thirty years of his life, and the task of liquidating his estate to pay off his vast debts now fell to his son-in-law Thomas Weldon, the husband of his daughter Charlotte. By the time Blomefield arrived in the muniment room at Oxnead Hall the Paston family seat in Norfolk, now in a state of ruinous disrepair the Earls books, paintings and furniture had already been sold. Before the remaining lands were disposed of and the house abandoned, Blomefield spent two weeks among the old writings in the Paston archive, gathering material for the Topographical History of the County of Norfolk which he planned to publish, and bringing order to the jumbled piles of documents for the benefit of the Earls executors. At the end of the fortnight, he wrote to Major Weldon to report his findings.

There are innumerable letters, of good consequence in history, still lying among the loose papers, all which I laid up in a corner of the room on a heap, which contains several sacks full; but as they seemed to have some family affairs of one nature or other intermixed in them, I did not offer to touch any of them, but have left them to your consideration, whether, when I go to that part of the country, I shall separate and preserve them, or whether you will have them burned, though I must own tis pity they should; except it be those (of which there are many) that relate to nothing but family affairs only. I have placed everything so that now the good and bad are distinguished and preserved from the weather, by which a great number have perished entirely.