T he Paston Letters, written by a fifteenth-century family of the Norfolk landed gentry, their friends, and their associates, comprise more than a thousand letters and documents. Dealing with family and domestic problems, litigation and business affairs, they have no literary pretensions and only peripheral political significance. Their value to historians lies in the familys very ordinariness and the letters consequent wealth of information about manners, morals, lifestyle, and attitudes in the late Middle Ages. Their existence itself reflects the increasing literacy of the gentry, as well as the troubled times that separated family members and imposed written communication.

The Paston archive first came to public notice in 1787 when a Norfolk gentleman named John Fenn, a member of the enthusiastic class of amateur historian-archaeologists known as antiquarians, published two volumes under the cumbersome title Original Letters, Written During the Reigns of Henry VI, Edward IV, and Richard III, By Various Persons of Rank and Consequence . The title was misleading. Most of the correspondence was not that of persons of rank and consequence but of three generations of the Paston family and their compatriots, persons of only middling rank and consequence.

The publication was greeted by an accolade from Horace Walpole, earl of Orford, himself a famous composer of letters, which gave it an immediate boost. Walpoles appreciation was principally for the occasional letters of the persons of rank: Lord Rivers, Lord Hastings, the Earl of Warwick. What antiquary would be answering a letter from a living Countess when he may read one from Eleanor Mowbray, Duchess of Norfolk?1 On the other hand, Hannah More, a prominent blue-stocking, deplored the letters want of elegance and their barbarous style. She concluded that they might be of some use as a historical resource but that as letters they have little merit.2

Mrs. Mores (privately expressed) opinion was not generally shared, and the book was a success in court and literary circles, resulting in Fenns being knighted by King George III. The first two volumes were followed by a third and fourth in 1789, while a fifth, left ready for publication by Fenn at his death in 1794, was published by his nephew William Frere in 1823.

The Fenn edition, like subsequent versions of the Paston Letters, was limited in time frame to the fifteenth century though the familys correspondence, after a break, continued through the seventeenth century. It is the letters and documents of the fifteenth century, by presenting a coherent record of three generations of the family, that constitute an incomparable resource for the social history of the time and a record of a pivotal class of the late Middle Ages. Sandwiched between the nobilitya few score families, most of them very wealthyand the upper (yeoman) tier of the peasant masses, the English gentry numbered only about a thousand households, filling the professions, especially the law, and owning enough property to ensure a decent standard of living.

But the Pastons are more than a microcosm of a class: they are individuals with personalities and stories that are accessible to us, once the obstacle imposed by language has been overcome. With the exception of a few in French or Latin, the letters are written in a language somewhere between the Middle English of Chaucer (d.1400) and the Early Modern English of Shakespeare; in fact, they present, in addition to the raw material of social history, a record of an important stage in the history of the English language, just before and just after the introduction of printing. Geographically, the Paston idiom is located in the East Midlands. North, South, and Midland English differed on a scale that made Northern speech difficult for Southern speakers to understand; Midlanders understood both.3 East Midland speech, used by Court and government circles and by the Justices of Assize, was in the process of becoming modern English.4 In its transitional fifteenth-century state, it presents difficulties for the modern reader in vocabulary, grammar, and spelling. Some words have since passed out of the language; others have changed their meaning; old verb and pronoun forms persist; word order is confusing.

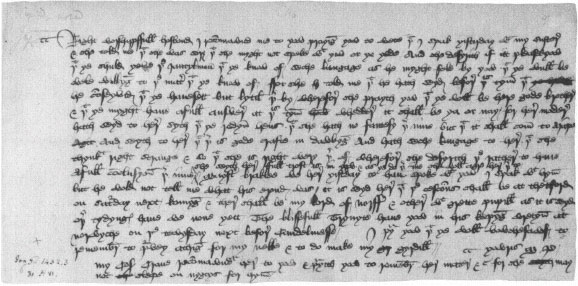

Spelling, however, is the greatest obstacle, differing not only from the modern but from letter to letter, within a letter, or even within a sentence. Evidently English readers of John Fenns day were closer to Middle English than we are today; few modern readers would have the patience to read the Paston letters in their original form. In this book the prose is translated for the sake of intelligibility without, so far as possible, sacrificing contemporary flavor. For example, Margaret Pastons letter to her husband John, about a possible marriage for his sister, Elizabeth, reads in the original:

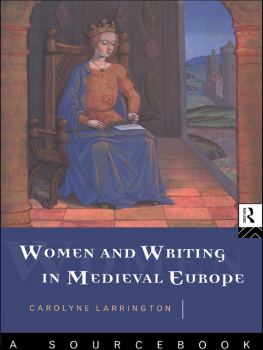

Right worshipfull hosbond, I recommawnd me to yow, praying yow to wete that I spak yistirday with my suster, and she told me that she was sory that she myght not speke with yow or ye yede; and she desyrith if itt pleased yow, that ye shuld yeve the jantylman that ye know of seche langage as he myght fele by yow that ye wull be wele willyng to the mater that ye know of; for she told me that he hath seyd befor this tym that he conseyvid that ye have sett but lytil therby, wherefor she prayth yow that ye woll be here gode brother, and that ye myght have a full answer at this tym whedder it shall be ya or nay. For her moder hath seyd to her syth that ye redyn hens that she hath no fantesy therinne, but that it shall com to a jape, and seyth to her that ther is gode grafte in dawbyng, and hath seche langage to her that she thynkyt right strange, and so that she is right wery therof, wherefor she desyrith the rather to have a full conclusyon therinne. She seyth her full trost is in yow, and as ye do therinne, she woll agre her therto.5 (See illustration in Chapter 1)

Translation:

asking his help in finding a husband for his sister, Elizabeth. (British Library, MS. Add. 36888, f.91)

Right worshipful husband, I recommend myself to you, praying you to know that I spoke yesterday with my sister [-in-law], and she told me that she was sorry that she could not speak with you before you went; and she desires, if it please you, that you should give the gentleman that you know of such an answer that he might feel that you will be favorable to the matter that you know of; for she told me that he has said previously that he thought that you have set but little importance by it, wherefore she prays you that you will be her good brother, and that you might have a full answer at this time whether it shall be yes or no. For her mother has said to her since you rode hence that it shall come to a joke; and says to her that there is good art in putting on makeup; and has language to her that she thinks very strange, so that she is very weary thereof, wherefore she desires rather to have a full conclusion of it. She says her full trust is in you, and whatever you decide to do, she will agree to it.

Numerals in the letters are almost exclusively Roman, although Hindu-Arabic notation had long been introduced in Europe. (For claritys sake, this book writes out the numbers, or substitutes Arabic for Roman.) The Pastons probably employed the counting board (a version of the abacus) for their computations. Margaret makes a reference to Johns board, which, along with his coffers, required space to go and sit beside.6 The monetary system, inherited from the Romans, was universal in medieval Europe and preserved in England until the 1970s: in Latin, libri, solidi , and denarii , in English, pounds, shillings, and pence; twelve pence to a shilling and twenty shillings to a pound. Counting by dozens and scores of dozens apparently seemed natural to the Middle Ages. In the Paston Letters, pounds are expressed by the abbreviation li . (for libri , as for example, xx li .) for which this book substitutes the word pounds or the modern pound sign (); the abbreviations for shillings and pence are the same as in predecimal Britain: s. for shillings, and d. ( denarii ) for pence. In England another often-used unit was the mark, which equaled two-thirds of a pound, a relationship confusing to a modern observer but giving no trouble to the Pastons, who switched back and forth between pounds and marks with casual dexterity.