Touchstone

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2015 by Juliana Barbassa

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Touchstone Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Touchstone hardcover edition July 2015

TOUCHSTONE and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Akasha Archer

Jacket design by Laurie Carkeet

Jacket photographs: Front by Lazyllama/Shutterstock Images; Spine By Ksenia Ragozina/Shutterstock Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barbassa, Juliana.

Dancing with the devil in the city of God : Rio de Janeiro on the brink / Juliana Barbassa.

pages cm

A Touchstone book.

1. Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)Social life and customs. 2. Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)Social conditions. 3. City and town lifeBrazilRio de Janeiro. 4. Social changeBrazilRio de Janeiro. 5. Social problemsBrazilRio de Janeiro. 6. Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)Description and travel. 7. Barbassa, JulianaTravelBrazilRio de Janeiro. 8. Economic developmentBrazilRio de Janeiro. 9. Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)Economic conditions. I. Title.

F2646.2.B37 2015

981'.53dc23 2014042530

ISBN 978-1-4767-5625-7

ISBN 978-1-4767-5627-1 (ebook)

For my Cariocas Gabriel, Clara, Marina, Henrique, and Rafael

The drums, like thunder, drummed the tremulous hour.

Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION: OR, IS GOD BRAZILIAN?

It started as a persistent tapping, like impatient fingers on a tabletop: tah-cah-TAH tah-cah-TAH tah-cah-TAH.

I was on deadline, hunched over my desk in the back corner of the Associated Press newsroom in San Francisco, trying to block out the perennially ringing phones and the reporter chatter. This was October 2009. President Barack Obamas plan to reform health care was the news of the day, and my editors in New York wanted an article on what it meant for immigrants. I had a couple of hours to make something coherent out of the reports strewn on my desk.

On my screen, sentences refused to coalesce into paragraphs. Through the office din I heard that pulse, faint but insistent: tah-cah-TAH tah-cah-TAH tah-cah-TAH... TAH TAH. TAH TAH. Then it clicked. I knew that pattern: it was the call and response of surdos, the bass drums that drive a Brazilian samba beat. The sound was so out of place in the air-conditioned newsroom that my eyes flew up to the TVs that hung in clusters from the ceiling, tuned to the news. I walked over.

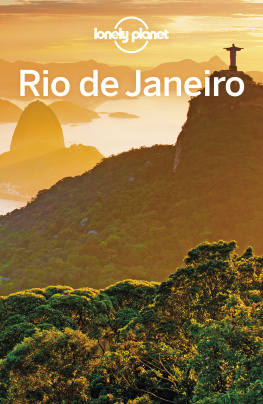

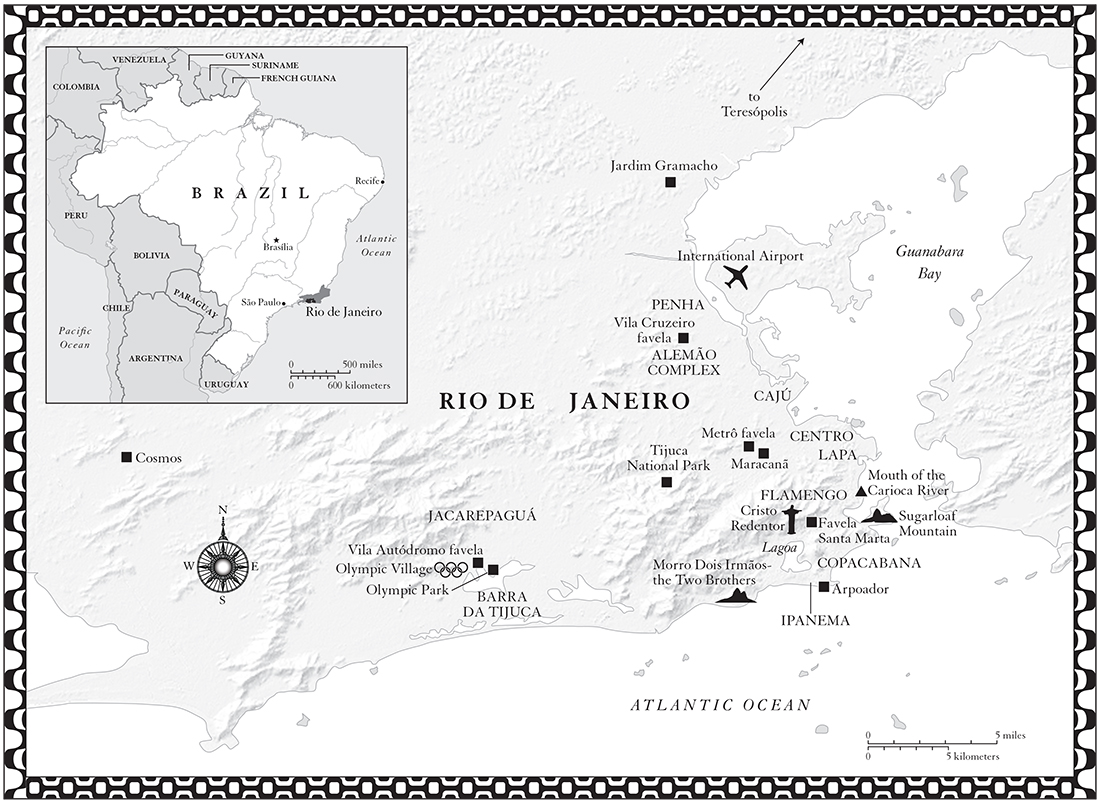

One of the tech writers was already there, craning his neck to watch, curious about the commotion. There was the long sweep of Copacabana Beach, the cobalt of the Atlantic. The white sand was thick with people, tens of thousands, skin glistening as men stripped off their shirts on the warm spring day and women danced, arms widespread, the whole crowd flashing Brazils green and yellow colors and heaving to the syncopated beat.

This was the day. BrazilRio de Janeirowas in the running to host the 2016 Olympics, up against Tokyo, Madrid, and Chicago. The announcement would be broadcast live on massive screens raised on the beach.

This wasnt the countrys first try. It had bid two times before and failed. But this run was different. Brazil was different. A copy of The Economist sat on my desk under the health care reports, folded back to an article on vast oil finds just off Rios shore. There had been other intriguing headlines recently. Brazil was lending money to the International Monetary Fund, after years of failing to pay its debt. Its middle class had grown by a population the size of Californias in less than a decade. Something remarkable was happening in this southern giant. Financial papers had picked up on it, even if to most foreigners it was still a place of poverty and parties, samba, soccer, and favelas.

The countrys recent good fortune and its Olympic bid made for good copy; as a journalist, I knew that. But my interest wasnt just professional. I was born in Brazil, although Id spent most of my life rambling from country to country, first as the daughter of an oil executive, and later as a reporter with a chronic case of wanderlust. Over time, the roots connecting me to my home country had grown long and thin, but Id kept them alive through annual visits and by collecting news articles such as the ones that littered my desk.

Recently, Id noticed a change in these articles. What had been occasional pieces, mostly short briefs about a burst of violence or a presidential election, came more frequently, and in greater depth. The world had begun to pay more attention to Brazil. The Olympic vote could push it right into the spotlight.

I watched as in Copenhagen the camera panned to Brazils president, Luis Incio Lula da Silva, a stocky man pumping a few more hands in the moments before the cities made final presentations to the International Olympic Committee. Brazilians affectionately shortened his name to Lula, as if he were one of the family. Being chosen to host the Olympics would give Brazilthe Brazil crafted during his tenurean unprecedented vote of confidence, a gold star to show that this forever-emerging nation had finally arrived. The International Olympic Committee had played that role before: Tokyo won the 1964 bid as Japan rose from the devastation of World War II. Seoul hosted the 1988 Games just when Korea was taking off, and China got the 2008 Olympics right as it was flexing its muscles on the international stage.

In the week leading up to the IOC decision there had been a scrum of press conferences with presidents and campaign trail stunts, making the run-up feel like something between a high school popularity contest and a political summit. The Madrid team flew in a liveried plane; Oprah Winfrey shilled for Chicago.

Still, as the Olympic Committee members gathered there was no clear favorite. Tokyo was a safe, functional alternative. Madrid already had most of the venues built. In a last-minute twist, Obama said he would deliver the U.S. pitch, becoming the first American president to address the IOC. His perfectly timed trip swayed the bookmakers. On the day of the vote, the money was on Chicago.

Whichever country won, it would face scrutiny and tremendous expense. The Beijing Olympics the year before had cost an astounding $40 billion, removed 1.5 million people from their homes, and left behind empty stadiums. The torch relay had sparked huge protests over Chinas human rights record; Id helped cover the marches in San Francisco.

Spain and the United States were mired in a global recession; Japans economy was faltering. And yet the contest was more intense than ever. Staging the worlds biggest sports bash was expensive, but voters loved it; it also gave the host country tremendous leverage to promote a particular agenda, whether it was fostering rapid urban renewal, picking up a lackluster economy, or showing off new political and economic might.