Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund.

Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2014 by Thomas S. Kidd.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Electra type by IDS Infotech Ltd., Chandigarh, India.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kidd, Thomas S.

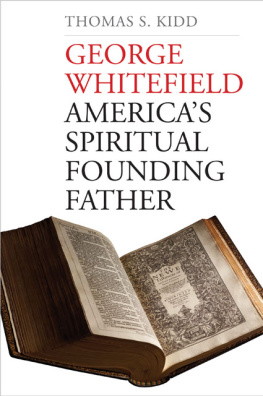

George Whitefield : America's spiritual founding father / Thomas S. Kidd.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-18162-3 (hardback)

1. Whitefield, George, 17141770. 2. EvangelistsGreat BritainBiography. 3. EvangelistsUnited States-Biography. 4. United StatesChurch history.

I. Title.

BX9225.W4K48 2014

269.2092-dc23

[B]

2014012873

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

On October 12, 1740, in the fading light of a cool autumn evening, the twenty-five-year-old evangelist George Whitefield ascended a platform on Boston Common. Before him stood twenty thousand people. If the crowd estimates were reasonably accurate, this was the largest assembly ever gathered in the history of the American colonies. (Bostons entire population was only seventeen thousand in 1740.) Whitefield had already seen crowds this massiveeven largerin the great city of London, but the teeming New England throngs, gathered in the regions small fishing villages and provincial towns, amazed him.

Sometimes the pressing people frightened him, too. There were volcanic outbursts of emotion. He regularly had to cut his preaching short, unable to be heard over the cacophony of weeping and screeching. At the Common, Whitefield implored the people to put their faith in Jesus Christ, the kind of sincere faith their Puritan forefathers had embraced. It did not matter whether their parents were Christians. It did not matter whether they prayed and attended church and read their Bibles. Whitefield wanted to know whether they had experienced the new birth of conversion.

Concluding the sermon, his countenance falling, he told them that it was time for him to go; other audiences needed his gospel preaching, too. Numbers, great numbers, melted into tears, when I talked of leaving them, Whitefield wrote. He had begun to forge a special bond with the American colonists. Boston people are dear to my soul, he confessed.

Reports about this wondrous boy preacher began to appear in the colonies newspapers in 1739. By 1740 he had become the most famous man in America. (In 1740 George Washington was eight years old, John Adams was four, Thomas Jefferson was not even born. Benjamin Franklins fame as a printer, which did not extend much beyond Philadelphia, was enhanced considerably by becoming Whitefields publisher.) Whitefield was probably the most famous man in Britain, too, or at least the most famous aside from King George II. From his humble beginnings in Gloucester, England, no one would have guessed that Whitefields celebrity would reach so far, so high, or so soon.

Three hundred years after his birth, George Whitefield is not entirely forgotten, but his fame now is far dimmer than it was on that fall evening in Boston. Today, Whitefields renown is surpassed by that of his friends, including Ben Franklin and Jonathan Edwards, the great pastor-theologian of Northampton, Massachusetts. Most U.S. history survey courses and textbooks still mention Whitefield, thanks to two major academic biographies, Harry Stouts The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism (1991) and Frank Lamberts Pedlar in Divinity: George Whitefield and the Transatlantic Revivals (1994). These biographies, as well as a surge of recent studies of the Great Awakening, have established Whitefield as a fixture in the standard story of American history for the foreseeable future. Still, we know too little about him.

I do not come to this new biography of the great evangelist with a historical axe to grind. All the major Whitefield biographies, from confessional Christian approaches such as Luke Tyermans The Life of the Rev. George Whitefield (2 vols., 1877) and Arnold Dallimores George Whitefield: The Life and Times of the Great Evangelist of the Eighteenth-Century Revival (2 vols., 1970, 1980), to Stouts, Lamberts, and Jerome Mahaffeys more recent books, make essential contributions upon which I gratefully build. Readers familiar with my work know that I am both a university-based historian and an evangelical Christian, so perhaps I can help bridge the academic and Christian perspectives on Whitefield that have clashed in recent decades. (More on this clash later.)

I admire the work of Tyerman and Dallimore, especially because they were not professional historians, but ministers. They painstakingly pieced together comprehensive biographies through archival research, consulting original sources and manuscripts whenever possible. Dallimore, a small-town pastor in Ontario, worked for thirty years on his biography, facing poverty and complaints from his parishioners that he was wasting time. Dallimore ultimately resigned his pastorate in 1973 so he could devote himself full-time to the biographys second volume. Tyerman and Dallimore appear constantly in scholars footnotes because they remain the two most detailed treatments of Whitefields own life and ministry.

Of course, Tyerman and Dallimore did not provide the kind of context for Whitefields life that one would expect from academic historians. Stout,

In two recent books on Whitefield, the communications scholar Jerome Mahaffey has expanded on earlier proposals by Stout and the historian Alan Heimert by considering how Whitefield became an Accidental Revolutionary, the man most responsible for priming America for its Revolution. Whitefield was the central figure in the process by which disparate colonists became Americans, prone to think in zealous, adversarial terms about religion, rights, and liberties. Whitefields Awakening may not have caused the Revolution, Mahaffey argued, but it had a profound conditioning influence on Americans as the Revolution approached. Heimert memorably argued that whether the enlightened sage of Monticello [Jefferson] knew it or not, he had inherited the mantle of George Whitefield.

Whitefield and commerce, Whitefield and religious celebrity, Whitefield and the Revolution: all these arguments have considerable merit, even if I have doubts about certain aspects of them. The main problem with these approaches, however, is that they do not really focus on Whitefields primary significance or on the way he viewed himself. The argument of this biography is straightforward: George Whitefield was the key figure in the first generation of Anglo-American evangelical Christianity. Whitefield and legions of other evangelical pastors and laypeople helped establish a new interdenominational religious movement in the eighteenth century, one committed to the gospel of conversion, the new birth, the work of the Holy Spirit, and the preaching of revival across Europe and America. Until now, we have not had a scholarly biography of Whitefield that places him fully in the dynamic, fractious milieu of the early evangelical movement. That is what I seek to do here.

Next page