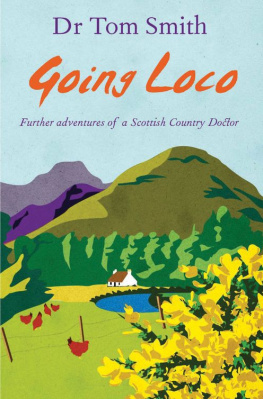

Title Page

A Seaside Practice

Dr Tom Smith

Publisher Information

2011 Watson Little

This digital edition published in 2011 under licence to Andrews UK Ltd

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior written consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Chapter One

Arrival

I had arrived in Collintrae on April Fools Day, 1965 - not an auspicious date. On April 3rd, the local newspaper, the Carrick Herald , kindly featured me on the front page. NEW DOCTOR SETTLES IN was the muted headline, and my career, from my birth in Glasgow to my schooling in Lincoln, and my medical training in Birmingham, was politely reviewed. I would have been encouraged were it not for the article immediately beside it.

Its headline was in larger, much bolder print. FIVE DEATHS IN THE STINCHAR COMMUNITY IN ONE WEEK. UNPRECEDENTED TRAGEDIES. Under it were five photographs of recently deceased people, all of whom would appear to have shuffled off their mortal coil in direct reaction to my arrival in the area. Apparently the papers staff had looked up the records. Never before had five people from our little collection of villages died in one week. It didnt matter that I hadnt actually seen any of them. Four had died in hospital and one in a road accident miles away, but the connection seemed sure and augured ill. The local newspaper obviously felt the same. It seemed that I was too young, and worse still, I had qualified in England.

With this less-than-encouraging coverage in the local press I had to tackle my first day as doctor, and this was to take place in Barrhill, one of the three villages under my care. Three times a week, the Collintrae doctor drives inland, up the valley of the river Stinchar through the village of Kilminnel to Braehill. The surgery there was in the house of a Mrs Jeanie Braidfoot, and had been fully kitted out by the previous doctors, all of whom had stayed a while then left for better, bigger and less solitary practices. Like a mother hen Jeanie had looked after my predecessors, and the tradition would, it seemed, continue with me.

Seven or eight elderly ladies were busy chatting in Mrs Braidfoots front room, which served as my waiting room. They didnt look ill. They could have been there for afternoon tea, not to see me. But see me they were determined to do. It became clear that it was I, not them, who was to be examined and assessed. These ladies had seen off five doctors in the last decade, and they were going to add another one to their list.

My initial glance at the room had missed a much younger woman, who had been sitting behind the door. When I called for the first patient, she walked across the hall into the room that served as the surgery. My first thought was relief: she looked well and happy enough. I didnt have the sinking feeling that comes when an obviously ill person walks into the room. That is, until she rolled up her sleeve.

On the front of her forearm, just above the wrist, was a skin problem that I had never seen before in a person - only in gory photographic detail in my skins textbooks. It was a lump about two centimetres across, fiery and infected, raised above the skin and with a thickened edge. It looked horribly sore. Mary Bryant, its owner, said it wasnt. In fact, it was painless.

That wasnt good news. If it wasnt painful, all my training suggested that it was malignant. The medical name for it was a squamous cell cancer, and at that size it was surely very advanced. It had appeared and developed in only a week, so I assumed it was growing extremely fast. With a sense of real foreboding I reached for the telephone.

I was lucky. The consultant in skins was doing a clinic in Ayr that afternoon, and if I could get Mary up to him before it closed, he would see her that day. But the conversation took a curious turn. It went something like this:

Me: I wonder if you could see this young lady urgently. Im worried that she has a very fast-growing lesion on her wrist. It looks like a squamous cell problem (Mary was in the room with me, so the language had to be guarded).

The dermatologist: Oh yes? And what does she do, this lady?

Me: Shes a shepherds wife.

The dermatologist: Oh yes? And how long have you been in Braehill?

Me: I started today.

The dermatologist: OK. Send her in. Ill see her for you.

Ayr was an hours drive away, so I wrote a letter to the dermatologist, gave it to her and packed her off. I expected to hear later that she had been admitted to hospital.

Around four oclock the phone rang. I was still wading through my series of elderly ladies. It was the dermatologist. The conversation was brief and to the point:

Him: So where did you train, doctor?

Me: Birmingham.

Him: Not many sheep in Birmingham, then?

Me: Er, no.

Him: Youve just sent me a case of orf.

Me: Pardon?

Him: Orf. Sheep pox. She has caught it from feeding a lamb. Never heard of the Folies Bergres?

Me: Pardon?

Him: The Shepherdess Follies. Its in Paris. Read up about it. Welcome to the district. And dont worry, youre not the first to make that mistake.

Me: So how do I treat it?

Him: You dont. It gets better on its own. Wait and see.

The dermatologist, Tommy Cochrane, and I eventually became great friends. We looked after many patients together, but he never let me forget that first conversation. Orf has three lines in the most complete textbook of medicine, and doesnt appear in any of the others. Its related to smallpox and cowpox. Only people who work with sheep catch it, and once infected they are immune for life from further orf attack and from other pox viruses. Lambs get it around their mouths, and it spreads to humans who have to bottle-feed them.

So why the reference to the Folies Bergres? Its simple. Sheep farmers and their shepherdesses would catch orf at an early age. All it produced was that one patch. Sheep pox doesnt spread further in humans. So when the mark healed, they were unscarred and immune from smallpox. Two hundred years ago, everyone else caught smallpox. The survivors were pock-marked with pitted scars all over their bodies, and particularly their faces. Only shepherdesses and milkmaids (who caught cowpox in the same way) had smooth features and healthy complexions. So the Folies recruited shepherdesses for their shows.

My episode with Mary Bryant didnt do me any harm. Mary was a newcomer to the village and to farming, and didnt know about orf. If she had been a born-and-bred local she wouldnt have bothered me with such an obvious problem. But the locals understood that I had done my best for her, and that was all that mattered.

Chapter Two

Collintrae

The sleepy village of Collintrae lies on the south-west coast of Scotland, and stretches along a long shingle shoreline, its southern border being the mouth of the River Stinchar. Seen from the sea, there is a row of fishermans cottages bordered to the west by a solid sandstone harbour wall. Behind the cottages, more protected from the winter storms, is the heart of the village, where the landsmen, farm workers and foresters live. Where the village road meanders eastwards up the River Stinchars north bank towards the higher country, theres a smattering of bigger houses for teachers, bankers, lawyers and businessmen the commuters to Girvan thirteen miles to the north. In its single main street stands Collintraes one church, three pubs (the Ayrshire Scot has his priorities right), and three shops.

Seven miles up river, along that meandering road, lies Kilminnel, the centre for the local dairy and arable farmers, cosily settled into the valley floor, alongside rich alluvial fields and looking across at low, green, rolling foothills. Eight miles further on is Braehill, higher still, nestling in the valley between steeper, browner, heather-clad hills, where the sheep and beef cattle, grazing there all year round, have been enough to keep families reasonably comfortable for hundreds of years.

Next page