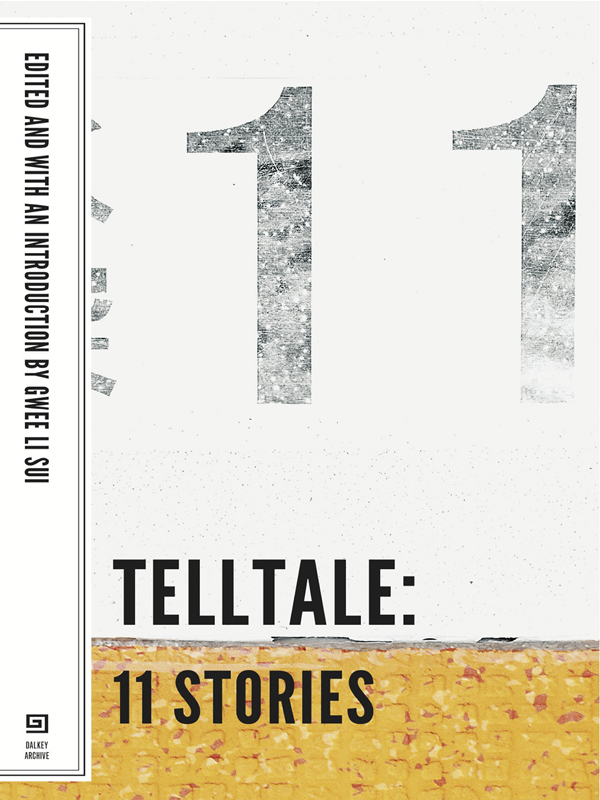

Gwee - Telltale : 11 Stories

Here you can read online Gwee - Telltale : 11 Stories full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Singapur, year: 2013, publisher: Dalkey Archive Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Telltale : 11 Stories

- Author:

- Publisher:Dalkey Archive Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- City:Singapur

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Telltale : 11 Stories: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Telltale : 11 Stories" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Abstract: A landmark anthology of short fiction from Singapore. Read more...

Gwee: author's other books

Who wrote Telltale : 11 Stories? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Telltale : 11 Stories — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Telltale : 11 Stories" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Telltale:

11 stories

Edited and with an introduction by

Gwee Li Sui

DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS

CHAMPAIGN / LONDON / DUBLIN

Gwee Li Sui

In our most essential form, as not citizens, professionals, students, parents, or children but mere humans, our fascination with stories does not come as a choice. When we are not reading a book or the news or following some drama on stage, on screen, or in a narration, we are involved in our own generation of stories that are either purely imaginative or about our otherwise dull and chaotic lives. These stories to which we contribute on a daily basis do not always appear to us as stories in view of their entanglement with our deep-seated understanding of self. Nationhood, globalisation, social and cultural identity, religious beliefs, modes of knowledge, family life, and personal ambition are all different kinds of storytelling we participate in. Thus, when we encounter a tale that actually declares itself as a tale, we do well to be a little more careful and reflect on what is here that must exceed our immediate enjoyment.

Consider the following short story that has been regarded by many as among the most perfect in the English language despite its economy of words and formal simplicity. The tale is written like the confession of a man who we recognise as mentally disturbed not just because of the unusual excitement and forwardness in the manner he speaks. This narrator may be intelligent, articulate, and very engaging, but he seems often uncomfortable with his own sanity, choosing repeatedly to test and confirm his fitness of mind with us. The oddity is telling and keeps us wary enough to avoid quick judgements and wait for more information to arrive via the narration. What we soon learn horrifies us: the speaker has, in fact, planned and just committed a murder, chopping up the body and hiding its parts under the floorboards of a house.

On every account, this shocking murder has been perfect; there is no clue left by the killer to connect him to any wrongdoing. Its execution has also been planned with such great care that even the victim sensed and communicated no danger for days until it was too late. Police officers, who then come a-knocking to investigate a neighbours claim of having heard a cry, are quickly persuaded that the man has only awoken from a nightmare. Emboldened by these successes, the murderer continues to talk in part to brag and in part to stay assured that everything still lies within his control. The more he shares though, the more he thinks that he is hearing some unnatural heartbeat pound louder and louder from under the floorboards. By the time the story ends, convinced of the officers actual suspicion, the man confesses to his crime and reveals exactly where he has concealed the body.

You may know this somewhat strange but riveting story as The Tell-Tale Heart, written by the Victorian master of mystery and the macabre, Edgar Allan Poe, and first published in 1843. During the time of our reading, we are bound to feel both intrigued by the criminal mind and terrorised by the eerie possibility of a corpses heart beating with growing intensity. Yet, a second after the story is over, we start to question whether the heart has twitched at all and what it is the killer must have experienced. Is it his own consciencea faculty he has kept suppressed in his amoral mind all this whilepounding away? Is his socialised sense of right and wrong what wills him to fail in order to indict his own arrogance and moral deviance? Or has his creative passion doomed him to want to overwhelm his audience and shock the officers, then some presumed judge, reporter, doctor, or prison warden, and lastly us?

Poes story conveys a lot of exciting thoughts, among which is the certainty that it is not simply about the perfect murder, crime and punishment, guilt, self-destructiveness, or madness. On an obvious and yet fundamental level, this is a story about stories, a parable about the way narratives function in a generic sense. What we encounter is primarily a tale with regular features: a setting, some characters, a basic plot, a climax, and a twist. More than that, the narrators mind operates on another level that involves the complex business of struggling to master the story he is conjuring in real time and we are reading. As his secret crime is itself the ground on which the story, his attempt to deceive, is built, we should find it no coincidence that, once the truth is revealed, the tale also comes to an end. We are given a very simple point: this story exists only because there is something more underneath, or, to put it differently, only because the truth remains unclear, the fiction is possible here.

In this sense, the pragmatists usual complaint that stories are useless and do not even speak of real things must be known as a red herring. Any opposition between truth and fiction is misleading since, if truth alone had been enough, fiction itself would not have come into being in the life of human civilisation. What fiction provides is the means with which we look round the corners of reality at all kinds of social and personal human neglect: what could be or might have been or truths not said, not said enough, or cannot begin to be said. Stories allow us as readers and writers to affirm or reassess our faithfulness to our own emotions and to one another as fellow humans; they give us the capacity to experience the world that lies outside the traditions of our knowledge and the systems of our everyday certainties. Pablo Picasso is often thought to have described art as a lie that tells the truth; this notion can also explain the work of fiction, the necessary dreaming through which we may approach the complexities in truths.

Can we now not see two more common mistakes in our standard treatment of literature, one relating to the powers of authors and the other to our interpretive freedom as readers? While the talents of good writers should indeed be admired, shared, and celebrated, it remains a fantasy on our part to believe that these possess knowing control over every meaning or pattern we may find in their texts. A writers genius and his or her thoughtfulness are not an exact fit: what Poe shows us is precisely the way less than conscious elementsespecially what deviates from a writers intentionscan sneak into the life of a story. For this reason, not just readers but writers themselves are always able to discover fresh significance whenever they engage or return to completed narratives. The understanding empowers us as readers with the certainty that we are fully permitted to interpret a story as we deem fit, so long as there is sufficient textual evidence for doing so.

That being said, we also ought to realise that readers are still not the clear receptacles who need only to draw on their own impressions and emotions to assess the depths in stories. The mistake here is a popular one, based on some notion that interpreting means feeling and that doing literature is just about communicating that feeling. What each act of reading does is quite subtle: it allows a reader to activate his or her own ability to enjoy a story via a private struggle, a process through which a part of him or her invariably gets left behind. Thus, as writers in the heat of creation are vulnerable to the way storytelling draws from their thoughts, emotions, and experiences, readers are open to a field of misdirections that relates to what they bring to the texts. This intrusion allows us to differentiate between mere reading and doing literature, the latter being a more conscious activity that involves our intuitions as well as our willingness to test, ground, correct, and study them. Its deeper implication is exciting here: we are, in fact, brought to see readers and writers alike as characters in the drama of how stories come alive!

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Telltale : 11 Stories»

Look at similar books to Telltale : 11 Stories. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Telltale : 11 Stories and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.