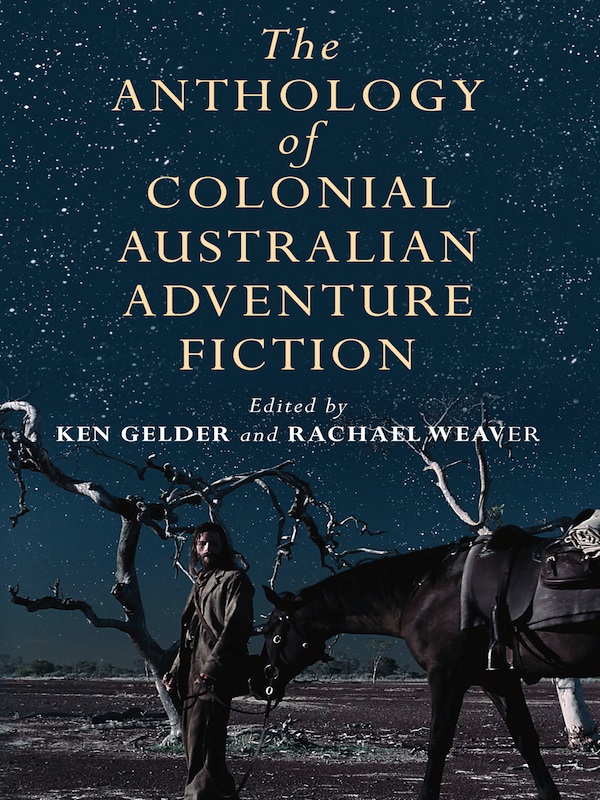

Colonial Australian Adventure Fiction

Ken Gelder and Rachael Weaver

For many colonial writers, adventure fiction was the most significant popular genre in Australia, the one that most authentically resonated with colonial experience. But it could also unleash the writers imagination. Adventure fiction takes its characters on a journey into unknown territories and regions; it can therefore sometimes overlap with fantasy fiction, especially if it populates those regions with strange people and their peculiar customs, as a number of stories do in this anthology. Homers Odyssey is generally regarded as Western cultures foundational adventure narrative, charting a heros elaborate journey back to his homeland and family after the Trojan Warduring which he does indeed encounter many strange and wonderful people. One of the stories we have included here, the Scottish-Australian Hume Nisbets A Queensland Iliad, brings Homer explicitly into the late colonial scene, as a lonely shepherd finds himself in the middle of an ongoing war between Aboriginal tribes worthy of even old Trojan and Greek. But colonial Australian adventure stories generally go in the opposite direction to Homers epic poem: travelling away from home, rather than returning to it. Migrationthe long journey out to Australia itself, whether voluntary or forcednaturally provides the source material for a great many colonial adventure stories, like Marcus Clarkes His Natural Life (1874), which has its central character, a wrongly-accused transported convict, leaving his homeland, never to return.

The convict story gives us a grimmer, darker kind of adventure narrative, one that can systematically shut down the possibilities inherent in the journey as it comes to define its protagonists almost exclusively in terms of loss: loss of freedom, homeland, inheritance, romance, dignity, and so on. But other colonial adventure stories are more optimistic, looking less at what has been lost and more at what might be gained from the journeys that their characters take. The colonial scene substantially changes the nature of adventure fiction, giving it a new lease of life by providing it with purpose and destination: leaving ones homeland behind, certainly, but often in order to carve out a new place for settlement and the pursuit of wealth and well-being. Adventure fiction and the colonial project are therefore intimately bound up with one another. But the relationship is often an uneasy one, and even the most positive adventure stories can be shadowed by darkness. The journeys that characters undertake are beset with danger and conflict, and the aspirations of settlement and the attainment of wealth that drive the action along are often impaired by the anguish and trauma of the journey itself. In these adventure stories, everything comes with a price.

Colonial Australian writers were influenced by popular American adventure novelists like the contemporary Bret Hartewho wrote about life on the Californian goldfieldsor the earlier frontier novelist Robert Montgomery Bird, whose virulently racist tale of a Kentucky Quaker taking revenge against Native Americans, Nick of the Woods (1837), provides one of the shepherds in N. Walter Swans Two Days at Michaelmas with an available model for killing a number of local Aboriginal men. People dont meet with the escapes of the Quaker, he says, critical of the ease with which Birds avenging hero avoids punishment. Its one of our cheap romances, you know, and cheapness and sensationalism go together. Its only hut literature. The shepherds throwaway comment is revealing, linking an ephemeral form of literature to an early, transitional phase of colonial settlement. But his rejection of this American adventure novel is generic in another way, too, because the colonial Australian adventure narrative often claims a relationship to actual settler experience that is more hard-edged and authentic. It, too, can be virulently racist, as many of the stories in this anthology will show. Descriptions of violence against Aboriginal people can unfold in lurid, graphic detail, and there is generally no attempt to gloss over or conceal atrocities and killings as settlers defend the properties and territories they lay claim to. Swans story gives this a particular emphasis, as the murders of Aboriginal men are seen through mirrors or happen just out of view while the dead and dying look back at their killers. The narrative moves away from hut literature as settlement is consolidated later on, but the newer homestead remains tainted by its history of colonial violence. Two Days at Michaelmas is a story that reflects on its predicament, at least to a degree, even pausing for a moment as the narrator wonders about the racist use of the word nigger to describe Aboriginal people. In other stories in this anthology, that word is used casually and oftenwith an insistence that might surprise some readers today. But this is merely one aspect of the colonial Australian adventure storys overall project, to chronicle the horrors and brutalities of colonial exploration and settlement and to confront readers with these accounts as a matter of sheer, raw experience.

The stories in this anthology therefore take their characters into the remotest parts of Australia, where settlement barely has a foothold and where the very notion of home is precarious. The narrator of William Sylvester Walkers Fighting the Flood reflects this at the beginning of the story, selling his outback Queensland station, returning to England, and then migrating back to Australia once more to find the outback station tenantless and derelict with the new owners yet to arrive. If I shut my eyes, he muses, I could easily fancy that my trip to England had been but a myth, and that I was, and had been all the time, still in Australia. Here, it is as if the return home had never happened: as if this remote station, with its immediately invoked threats of Aboriginal attack and infiltration, is his natural destination. Swans narrator is also drawn to his remote bush hut, an animated, defiant place that soon literally comes under attack. In Hume Nisbets A Queensland Iliad, a shepherd sits in a gum tree beside his hut and each day counts the number of sheep on his employers station, condemned, like an Australian Sisyphus, to a lifetime of drudging repetition. The setting is harsh, heat-baked and deathly, a long way, as the story notes, from the earlier pastoral verse of Nisbets fellow Scot, the Ettrick Shepherd James Hogg. An assault on the lonely shepherds hut by warring Aboriginal tribes leads to an erotic encounter that sustains him even as it robs him of the few possessions he has left. This is a story about a character who gives up everything in order to defend a piece of property he doesnt even ownsomeone for whom home is now barely a distant memory and the future is little more than a fantasy he can never hope to realise.

There are several stories in this anthology about lonely shepherds in remote bush huts whose mundane, chore-driven existences are suddenly jolted by unexpected encounters that test their loyalties to the squatters who employ them. Ernest Favenc was one of Australias most prolific colonial adventure writers, writing around a hundred and fifty short stories for journals including the Bulletin , the Australian Town and Country Journal , and Cosmos Magazine . Like Guy Boothby and Hume Nisbet, he was also an experienced explorer and traveller. The Hut-Keeper and the Cattle-Stealer looks back to an earlier time of real living shepherds far away from civilisation. But it also marks itself out as a post-settlement story that has already survived the conflicts with Aboriginal people that Nisbets story had chronicled. In the past days the blacks had been troublesome, Favencs narrator says, but now they were all gone, so there was no harm to be apprehended from them . Favencs story nevertheless exploitsand reanimatesthis history when a stranger tricks the hut-keeper into believing that he is seeing the ghost of a man who hanged himself out of remorse for the terrible killings that had once taken place so close to where he now lives. The adventure in this story is therefore generated not by Aboriginal conflict at all, butas it turns outby cattle rustlers and horse-stealers, culminating in a breathless chase on horseback. Other stories in this anthology also cut themselves free of earlier colonial atrocities against Indigenous people in order to redefine the threat to the pastoral economy, introducing a new cast of enemies and a new paradigm for adventure fiction. As colonial settlement is consolidated, the homestead moves to centre stage; yet the process of consolidation plays itself out over and over, as if it is never allowed to achieve finality. Defending the security of the colonial homestead becomes a key theme of the colonial adventure story.