Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. CONTENTS For Frank Bidart Acknowledgments I am grateful to the friends and advisers who have given me the benefit of their learning, judgment, and encouragement. R.P. R.P.

FOREWORD In-spite of Dantes reputation as the greatest of Christian poets, there is no sign of Christian forgiveness in the Inferno. The dominant theme is not mercy but justice, dispensed with the severity of the ancient law of retribution. The moral system of Hell owes more to ancient philosophy than it does to medieval classifications of virtues and vices, while the landscape of the underworld derives from Virgil more than from the poetically impoverished visions of the Middle Ages. The punishments themselves are reminiscent of ancient mythology, or perhaps even of the Marquis de Sade, but certainly not of the Gospels. Christ is never directly mentioned, we are told that pity should be extinguished here, and perhaps worst of all, the pain and despair of the damned seem to separate them from the rest of humanity and from one another, leaving them radically alone in the midst of an infernal crowd. A city, according to St.

Augustine, is a group of people joined together by their love of the same object. Ultimately, however, there can be only two objects of human love: God or the self. All other loves are masks for these. It follows that there are only two cities: the City of God, where all love Him to the exclusion of self, and the City of Man, where self-interest makes every sinner an enemy to every other. The bonds of charity form a community of the faithful, while sin disperses them and leaves only a crowd. In Dantes poem, Hell is the parody of a city, point zero in the scale of cosmic love.

Like Augustines City of Man, it is meant to represent the social consequences of insatiable desire when it remains earthbound. The City of God and the City of Man were thought to be spiritual states, the antithetical allegiances of those who actually live together in the real city. At the Last Judgment, sinners and saints would be definitively separated and sent to their respective cities, Heaven or Hell. The earthly city was therefore an encampment in which saints and sinners met and mingled as pilgrims en route to opposite destinations. Once they arrived at their respective goals, however, the damned were forever separated from the blessed. Dantes Inferno is a vision of the City of Man in the afterlife, which is why it contains no glimmer of forgiveness.

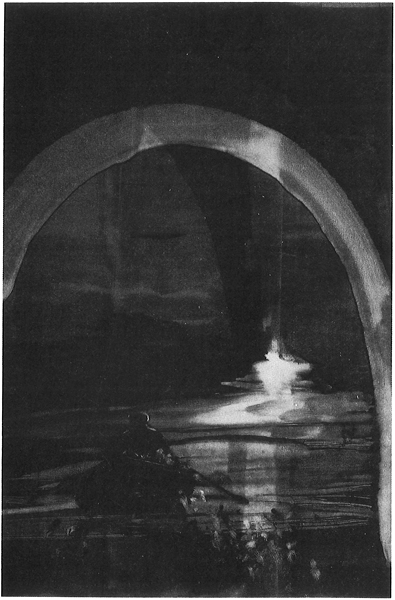

At the same time, it may also be thought of as a radical representation of the world in which we live, stripped of all temporizing and all hope. Hell is the state of the soul after death, but it is also the state of the world as seen by an exile whose experience has taught him no longer to trust the worlds values. The ruined portals and fallen bridges of Hell are emblems of the failure of all bonds among the souls who might once have been members of the human community. The sense in which Hell stands for the real world has never been lost on Dantes readers. What medieval readers would have referred to as the moral allegory reappears in contemporary interpretations by authors as diverse as Albert Camus ( The Fall ), where the infernal city is Amsterdam, and LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka), whose nightmare in the Newark ghetto is entitled The System of Dantes Hell. The principal dramatic contrast in the poem is between the pilgrim and his guide on one hand, who are journeying through Hell, and, on the other, the souls they encounter, who are imprisoned there forever.

The progress of the poem is measured by the journey, while the episodic encounters provide the substance of what Dante has to tell us about his life and times. Because of the contrast between the perspective of the pilgrim, who looks forward to his salvation, and the perspective of the damned, who have no future, conversation in Hell is charged with irony. Much of what the sinners have to say about their lives or their actions is undermined by their guilt or self-delusion. Their testimony is self-serving, as one would expect of any prisoners account of his or her conviction, except that here, as we learn from the inscription on the gates, all have received the same sentence, with no hope of appeal, and none has been framed. Justice in Hell is meant to be objective, measured out by a bureaucratic monster in proportion to the specific gravity of the sin. Such a mechanical administration of punishment leaves no room for judicial error or caprice.

Few of Dantes readers have derived much satisfaction from the triumph of this somewhat anonymous justice. Like Dantes protagonist, we find ourselves moved by the souls in Hell despite the moral system that condemns them so pitilessly. Where divine justice sees only black or white, we find mitigating circumstances. If Francesca is an adulteress, she is also a victim of literary seduction. Brunetto is a sodomite, but he is also a father figure who taught the poet how to make himself eternal. Ulysses is a thief, yet he pronounces an oration on the dignity of man.

The irony in these portraits derives from the fact that the prodigious historicity of Dantes characters, their individuality, seems to matter not at all in the way they are classified. In the either/or of the afterlife, distinctions are obliterated and the souls place in Hell is determined dispassionately, by the flick of a monsters tail. For a modern interpreter, the easiest way to deal with irony such as this is to ignore it, to assume that the abstract moral system is irrelevant to a discussion of the great figures of the Inferno. Such an approach goes back to Coleridge, who proposed that we suspend disbelief in order to appreciate the power of Dantes poetry without endorsing the religious conviction that it claims as its inspiration. In this century, Benedetto Croce suggested that since we are no longer concerned in the modern world with medieval theology, we may safely ignore it and consider only the works lyrical passages. The preference for feeling over meaning in poetry was later to reappear in the work of Erich Auerbach, who maintained that we should separate Dantes didactic intent from his power of representation.

In his masterful reading of Canto X in his book Mimesis, he conceded that Dante intended to give his characters an allegorical meaning, but claimed that the power and the historicity of his characterizations were so great as to overwhelm whatever doctrinal meaning they were meant to convey. Over the centuries, according to Auerbach, the sheer force of Dantes verses gradually came to subvert his moralizing intention, transforming a medieval system of punishments and rewards into an autonomous, secular world, much like this one, in which thoroughly human characters no longer signify anything, as Dante may have wished, but simply are in all of their tragic humanity. A reading such as this runs the risk of ignoring something essential about the poem. The clash between the humanity of the damned and the implacable judgment to which they are subjected is not simply an accident of history, the abyss that separates medieval standards of morality from our own, but rather reflects a fundamental division in Dantes own consciousness. Irony in the Inferno arises from the discrepancy between the perspective of the pilgrim, which is much like ours, and that of the poet, who, by journeys end, claims to share Gods view. The distance that separates the travelers navet from the omniscience of the poet is the poems story: the transformation of the pilgrim into the poet, whose work we read.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. CONTENTS For Frank Bidart Acknowledgments I am grateful to the friends and advisers who have given me the benefit of their learning, judgment, and encouragement. R.P. R.P.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. CONTENTS For Frank Bidart Acknowledgments I am grateful to the friends and advisers who have given me the benefit of their learning, judgment, and encouragement. R.P. R.P.