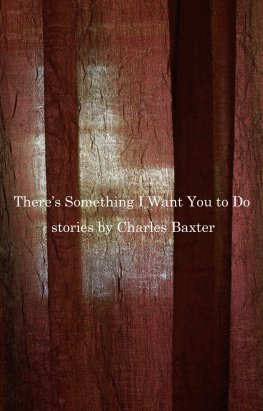

Charles Baxter

Charles Baxter is the author of the novels The Feast of Love (nominated for the National Book Award), The Soul Thief, Saul and Patsy, Shadow Play, and First Light, and the story collections Believers, A Relative Stranger, Through the Safety Net, Gryphon, and Harmony of the World. He lives in Minneapolis and teaches at the University of Minnesota and in the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College.

A LSO BY C HARLES B AXTER

Fiction

Gryphon

The Soul Thief

Saul and Patsy

The Feast of Love

Believers

Shadow Play

A Relative Stranger

First Light

Through the Safety Net

Harmony of the World

Poetry

Imaginary Paintings and Other Poems

Prose

The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot

Burning Down the House

As Editor

A William Maxwell Portrait (with Edward Hirsch and Michael Collier)

The Business of Memory: The Art of Remembering in an Age of Forgetting

Bringing the Devil to His Knees: The Craft of Fiction and the Writing Life (with Peter Turchi)

The Collected Stories of Sherwood Anderson

The Would-be Father

from the collection Gryphon

Charles Baxter

A Vintage Short

Vintage Books

A Division of Random House LLC

New York

Copyright 1984, 2011 by Charles Baxter

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies. Previously published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, in 2011, and subsequently published in paperback by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, in 2012.

The Would-be Father appeared in book form in Harmony of the World (University of Missouri Press, 1984, and subsequently published by Vintage Books in 1997).

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for Gryphon is available at the Library of Congress.

Vintage eShort ISBN: 978-1-101-91166-2

Series cover design by Joan Wong

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

Contents

The Would-be Father

WIPING OFF THE kitchen counter after dinner, Burrage happened to glance at the window over the sink and saw a womans face outside, peering in. The face had an inquisitive but friendly expression. It belonged to Mrs. Schultz from across the street, who tended to wander around the Heritage Condominium complex in the early evening while under the influence of powerful medications prescribed for her after-dinner and bedtime pains.

Hi, Mrs. Schultz, Burrage said, waving a sponge. Are you all right? Do you know where you are?

I think so, she said, waving back. Her gray hair was bundled at the top of her head, and the lines around her mouth rose when she smiled. I think I know where I am, if Im across the street and if you are who I think you are. I wanted to see that boy of yours. Also, Im thirsty. Can you pass a glass of water to me through this window?

I cant, Mrs. Schultz, Burrage said. Looking boyish and preoccupied, as was usual for him, he pointed at the window. Screens. And Gregorys already in his pajamas. See how late its getting? Mrs. Schultz glanced up, but it was still too early for stars. All the same, she nodded. Let me take you home. He dried his hands, poured a glass of water, and glanced down the hall. Gregorys door was closed, but Burrage could hear him singing. He carried the water outside to where the old lady stood near the arborvitae, slowly moving her left hand back and forth in the air. Burrage realized that she was trying to brush away gnats. Here, he said, putting the glass in her other hand. She sipped it, thanked him, and gave it back. Then she took his arm, and together they crossed the street. It was spring: he could hear children playing softball in the distance.

You said it was late, she said, but I dont see any stars.

They walked up the sidewalk to her front door, which was wide open, and Burrage turned her around so that they faced his house. He could smell onions, or something acidic, coming from the inside of her condominium, a permanent smell and a sign that she had lost the knack of effective housekeeping.

The days are longer now, Mrs. Schultz. Daylight savings time. Look over the roof of my garage at the sky. What do you see? Do you see anything?

I see a dot, she said.

Thats Mars, Burrage told her, letting out a breath with the word. The red planet. So you see? It is getting dark. Im leaving you here, okay? You should do yourself a favor and go inside now. Try to get some rest. Will you be all right? Mrs. Schultz stared at his shirt buttons. You should try to be all right, he said.

Oh, its you Im worried about, not me, she said. What a man in your position does, after all. And that dot, Mars. Its right over your house, isnt it? Its not over my house. She looked at him with her Im-not-so-dumb face. Thank you anyway. Ill go in now. Say good night to that little boy of yours.

I will.

She turned once more and went in. Burrage watched her trudge down the hall toward the living-room chair in front of the perpetually blaring television set. He reached inside her door to make sure the lock was set and then closed it before going back.

Gregory was kneeling at the side of his bed, his arms stretched out over the patchwork quilt, his fingers clasped tightly together. The only illumination in the room came from the Scotty dog night-light, which cast a pale glow on the bed and dresser and made them look like toy furniture used in a circus act. Gregory, who was five years old, was praying to Santa Claus. With his face buried in the quilt, his words broke out with difficulty, a mumble of wishes.

On the opposite side of the room was a narrow rocking chair, next to a low table on which was placed a windup double-decker bus and an ashtray. Above them was a wall poster of Paddington Bear, a poster the boy had outgrown. Burrages routine was to go into the room, kiss Gregory good night, light up a cigar, and turn on the boys cassette recorder, which would play the same selection of tunes as always, Glenn Millers greatest hits, starting with Moonlight Serenade. When Burrage had been a boy himself, suffering from asthma and unable to sleep, his mother would play Glenn Miller on the phonograph. In this way he became accustomed to falling asleep to the big-band sound.

His prayers finished, the boy climbed into bed and waited for Burrage to tuck him in. He was used to Burrages cigars and now liked the smell at bedtime. After Burrage entered, he kissed Gregory and, as usual, sat down to be close to the ashtray, before tapping the button on the recorder.

Where were you? Gregory asked.

Mrs. Schultz was over here. I had to help her back across the street. He waited a moment. Did you say your prayers?

Yeah, the boy said. He picked up his stuffed dragon and made a sound.

Was that a roar, Burrage asked, or a yawn?

Hes sleepy, the boy said. Tell me a story. Tell me a story with me in it. Tell me my horoscope. As always, he tripped over the word. Whats happening tomorrow?