2017 John Baxter

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, except brief extracts for the purpose of review, and no part of this publication may be sold or hired without the express permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Baxter, John, 1939- author.

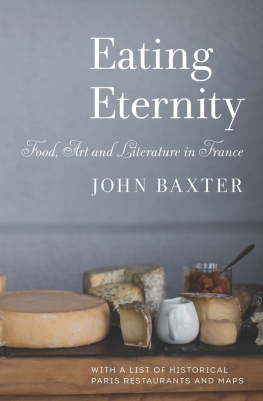

Title: Eating eternity: food, art and literature in France / John Baxter. Description: New York: Museyon, [2017] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017013175 (print) | LCCN 2017014244 (ebook) | ISBN 9781938450945 (e-Pub) | ISBN 9781938450952 (e-PDF) | ISBN 9781938450969 (Mobi) | ISBN 9781940842165 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Gastronomy--France. | Dinners and dining--Social aspects--France. | Arts and society--France--History. |

Artists--France--Social life and customs. | Cooking in literature.

Classification: LCC TX637 (ebook) | LCC TX637 .B39 2017 (print) | DDC

641.01/30944--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017013175

Published in the United States and Canada by:

Museyon Inc.

1177 Avenue of the Americas, 5 Fl.

New York, NY 10036

Museyon is a registered trademark.

Visit us online at www.museyon.com

ISBN 978-1-940842-16-5

0719040

Printed in China

To Charles DeGroot and the members of that island of lucidity, fellowship and gourmandise, the Paris Mens Salon.

INTRODUCTION

Show me another pleasure like dinner which comes every day and lasts an hour.Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, senior advisor to Napoleon I, Emperor of France.

Six foreign food writers, 15 minutes late for their reservation, piled into a tiny Paris restaurant in the shadow of Htel des Invalides.

With a fixed professional smile, the matresse d guided them to their table, the largest in the room. As coats were shed, seating wrangled over, enquiries made about the location of the toilettes, little attention was paid to the glares of other diners, some of whom, having booked months before, were paying 500 a head for what, if three Michelin stars meant anything, was some of the best food in France.

Nobody in the party took time to note the smooth leather chairs, undulating walls of pale pear wood or the glass lighting fittings by master verrier Ren Lalique, souvenired from a carriage of the original Orient Express. (The nude nymphs and shepherds molded into the glass were intended, explained the chef on his website, to evoke ancient Romes most ecstatic ritual, the Bacchanal.)

Menus, proffered, were barely consulted, the journalists having opted for the tasting menu or menu de dgustation: a cruise in 12 dishes through the master chefs creations, a parade of flavors and textures designed to display his inventiveness and that of his team.

Watching from the staircase that led down to the subterranean kitchen, the chef judged the party ready to start eating, and dispatched the first course, careful to ensure that each diner received his or her plate at exactly the same moment: the so-called service Russe or Russian service at its most effective.

He was less pleased to see some of the journalists chatting at they ate. One even put down her fork, rummaged in her handbag for a notebook and scribbled a few lines. None commented on the food. Glaring, the chef descended into his underground domain.

Ten minutes later, waiters cleared the empty plates and served another course. As they did so, one journalist peered at his portion, then those of his colleagues.

Didnt we just have this?

Taking notice for the first time, the others agreed. What theyd been served was identical with what theyd just eaten.

Was this a glitch in the famously perfect service?

Were standards at Frances most select restaurant starting to slip?

A waiter was summoned. A few minutes later, he returned from the kitchen.

I spoke to the chef. And yes, he did send out the same dish twice.

But why?

He wants you to start the meal again. The first time, you were not paying attention.

AUTHORS NOTE: Portions of this book, in a different form, appeared in The French Riviera and Its Artists (Museyon, 2015) and in The Perfect Meal: In Search of the Lost Tastes of France (HarperCollins, 2013).

Eating Eternity

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

BON APPTIT!

Food as cultural symbol

A mong French works of art from the early 19th century, one, a lithograph dating from 1808, holds a special interest for anyone who takes a serious interest in what we eat and drink.

Called Les Cinq Sens (The Five Senses), its the work of Louis-Lopold Boilly. To illustrate all the senses in a single image, he crowds together five individuals, each signifying one of the avenues through which we perceive the world. As a girl sniffs perfume, a gentleman exercises his sense of touch by caressing her hand, while, above him, another presses his ear to a watch and, at the top of the picture, an antiquarian uses a magnifier to examine an objet dart.

Absorbed in their private sensations, none of the four notices the fifth. Eyes wide in appreciation, he holds a plate in one hand while licking the fingers of the other. Clearly, something hes just eaten has ravished his sense of taste.

By placing a contented eater at the center of his composition, Boilly leaves us in no doubt with which of the senses his sympathies lie. Much as one would expect an artist to place greater value on the eyes, he naturally, as a Frenchman, assigned a privileged role to the palate.

In 1825, Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, Frances premier philosopher of cuisine, wrote in The Physiology of Taste: The destiny of nations depends on how they feed themselves. To the generation that followed the fall of Napoleon in 1815, sweeping statements of this kind were not uncommon as its members searched for a new belief to motivate the continuing progress of Europe toward modernity. That food would play a part in this quest, and an important one, was a novel concept for most countries. Not so, however, for France.

For centuries, French culture was segregated into three tiers tat or estates: the peasants and middle class or bourgeoisie, who made up 80 percent of the population, the clerg or Catholic church and the noblesse or nobility. (In 1787, British politicians recognized a so-called Fourth Estate, the press).

Each estate signified its status by what it ate. The aristocracy consumed only what was noble; not of the earth. In their eyes, most vegetables, but particularly potatoes and turnips, were fit only for animals. They also ate no fruit that had touched the ground, since it was believed that such contact was poison. While an association with earth tainted the meat of cattle, sheep and pigs, animals that lived in the wild were considered edible. As with a warrior, the courage shown by a hunted and cornered animal also counted in its favor. The wild boar or

Next page