Praise for The Best American Poetry

Each year, a vivid snapshot of what a distinguished poet finds exciting, fresh, and memorable: and over the years, as good a comprehensive overview of contemporary poetry as there can be.

Robert Pinsky

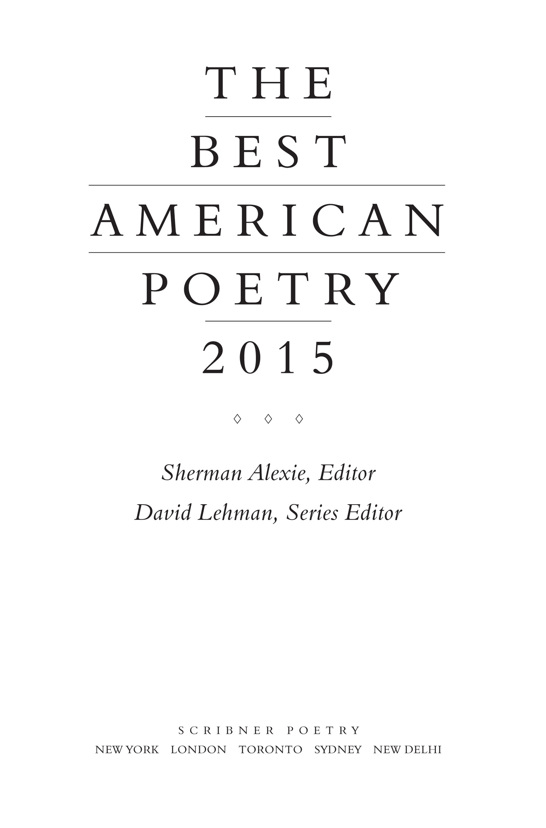

The Best American Poetry series has become one of the mainstays of the poetry publication world. For each volume, a guest editor is enlisted to cull the collective output of large and small literary journals published that year to select seventy-five of the years best poems. The guest editor is also asked to write an introduction to the collection, and the anthologies would be indispensable for these essays alone; combined with [David] Lehmans state-of-poetry forewords and the guest editors introductions, these anthologies seem to capture the zeitgeist of the current attitudes in American poetry.

Academy of American Poets

A high volume of poetic greatness... in all of these volumes... there is brilliance, there is innovation, there are surprises.

The Villager

A years worth of the very best!

People

A preponderance of intelligent, straightforward poems.

Booklist

Certainly it attests to poetrys continuing vitality.

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

A best anthology that really lives up to its title.

Chicago Tribune

An essential purchase.

The Washington Post

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

David Lehman was born in New York City. Educated at Stuyvesant High School and Columbia University, he spent two years as a Kellett Fellow at Clare College, Cambridge, and worked as Lionel Trillings research assistant upon his return from England. He is the author of nine books of poetry, including New and Selected Poems (2013), When a Woman Loves a Man (2005), The Daily Mirror (2000), and Valentine Place (1996), all from Scribner. He is the editor of The Oxford Book of American Poetry (Oxford, 2006) and Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present (Scribner, 2003), among other collections. Two prose books appeared in 2015: The State of the Art: A Chronicle of American Poetry, 19882014 (Pittsburgh), comprising all the forewords he has written for The Best American Poetry , and Sinatras Century: One Hundred Notes on the Man and His World (HarperCollins). A Fine Romance: Jewish Songwriters, American Songs (Nextbook/Schocken) won the Deems Taylor Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) in 2010. He teaches in the graduate writing program of The New School and lives in New York City and in Ithaca, New York.

FOREWORD

by David Lehman

When you write an annual column for nearly three decades, you may, in effect, be writing a book in discontinuous increments. But youre not necessarily conscious of it. You dont consult the previous years report before writing the present one, so when you put them together and reread the lot, youre likely to be in for a few surprises.

In 2015 the twenty-nine forewords that had appeared to date in The Best American Poetry were gathered in The State of the Art: A Chronicle of American Poetry, 19882014 and published by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Rereading the pieces in consecutive order, I was struck not only by unconscious repetitions (Wordsworth on pleasure and the formation of poetic taste, abundance as the defining trait of American poetry, W. H. Audens observations, Oscar Wildes paradoxes) but also, for example, by my evident partiality for the not only/but also rhetorical formula.

My pet peeves never let me down. I seem always to have been aghast at ad hoc pronouncements that pass for critical judgments and can rarely let it go unremarked when somebody lowers the limbo bar even in the act of elegizing some aspect of the poetry he despises. The December 2014 issue of The Atlantic provided a perfect illustration: a piece by James Parker lamenting, in the year of the Welsh poets centenary, the loss of Dylan Thomas. The articles title states the theme: The Last Rock-Star Poet. As the last of that Bardic breed, Thomas (Parker says) was worthy of our attention if not our unequivocal acclaimexcept that as a poet he didnt amount to all that much. In Parkers words, Fern Hill is gloop; Do not go gentle into that good night is inferior Yeats. That sentence, those judgments, are backed up by nothing. They are not even discussed, let alone substantiated, explained, argued. They are merely stated as if they were beyond disputearticles of received wisdom elevated to self-evident propositions. I wondered whether the writer had taken the time to reread Fern Hill or was he merely, as was possible, revolted by the memory of a younger version of himself, who had a deep crush on Thomas, having been smitten, as he admits, by the charm of the man, the charm of the boy, the shock-headed cherub-troll whod come waddling down to London from Swansea with a cigarette between his lips and a brown beer bottle in his pocket.

Fern Hill is a full-throated evocation of Edenic innocence, a Romantic recollection of an enchanted boyhood in the tradition variously exemplified by Thomas Traherne in the latter half of the seventeenth century and Wordsworth a century later. I like quoting the last three lines of the poem because they reach for the highest notes available in bringing this elegy for youth to a close:

Oh as I was young and easy in the mercy of his means,Time held me green and dyingThough I sang in my chains like the sea.

Is it possible that these lines make The Atlantic writer gag (gloop) precisely because they are so rich and so affecting and because such qualities are as outmoded as neckties? The sheer passion of the writing; the artful repetition of key phrases introduced earlier (young and easy, Time as a divine agent); the complexity of the final utterance, a subordinate clause that surpasses the main clause in its lyricism; the arresting simile at the very endthere is wizardry here, and wonderment, a sense of the natural sublime.

As for Do not go gentle into that good night, to dismiss Thomass famous villanelle as inferior Yeats is a pedantry, and a false one. Use Yeats as your standard, and few poets shall scape whipping. But for the record Yeats did not write villanelles, and the effects Thomas achieves in Do not go gentle are not those that the Irish poet was after. In the face of his fathers imminent demise, Thomas used the constrictive form dialectically, to discipline his feelings and to apply a restraint on his fountain of imagery and linguistic genius. The poems second stanza attests to the power that he achieved through the use of the strict form:

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,Because their words had forked no lightning theyDo not go gentle into that good night.

This is not a brand of poetry that would please the British poets of ironic understatement who chose Hardy as a master and whose greatest practitioner is Larkin. But it is a sterling example of Thomass method, which (he wrote in a letter) was to let one image breed another, let that image contradict the first, make, of the third image bred out of the other two together, a fourth contradictory image, and let them all, within my imposed formal limits, conflict. The method is at the service of something that can never stay out of fashion for long: the heroic note, defiance in the face of mortality.

Instant dismissal of greatness goes together with a second thing that reliably gets a rise out of me, the glorification of dumbness in American culture. A generously funded study indicates that there is a correlation between the elimination of course requirements and widespread ignorance of American history, civics, our government and economic structures. Although you might expect to see such a revelation in a satirical weekly, it gets half a page of a daily newspaper noted for its sobriety. Some readers may wonder whether we really need focus groups, task forces, or in this case a commissioned study to reveal what anecdotal evidence provides in abundanceor perhaps this academic exercise in stating the obvious itself lends credence to the argument. In any case, if you wanted the veneer of pseudo-scientific authority that only statistics can confer, you are now entitled to say that most college students do not know the length of a congressmans term, the meaning and purpose of the Emancipation Proclamation, or the name of the Revolutionary War general in charge of American forces at Yorktown.

Next page